The fallout from Springfield’s disastrous pension decision

We can’t go on like this

In a remarkable Friday afternoon news dump, at the end of last week Governor Pritzker signed a controversial pension bill that will increase pension benefits for many Chicago policemen and firefighters. The legislation had been on Pritzker’s desk for several weeks after passing unanimously in the state legislature towards the close of their latest session. During that time, it had been criticized by many people and institutions, including the Chicago Tribune, Civic Federation, Better Government Association, Civic Committee, Chicago CFO Jill Jaworski, state comptroller Susana Mendoza, and, of course, A City That Works.

We won’t bury the lede: this is a really bad outcome for Chicago. As a result of this change, the future liabilities of the police and fire pension funds have risen significantly. The city’s Department of Finance pegs the total liability increase at around $11 billion, while Ald. Bill Conway did some math estimating that the net-present value of the liability is somewhere around $3.9 billion. The result of that liability growth is that our funded rate falls from roughly 24% (already quite bad) to an abysmal 18%. It’s the fiscal equivalent of taking a long look at a swimmer struggling to keep their head above water, and then tossing them a cinderblock.

The actual impact

For context, a worker’s pension is generally calculated based on the average of several years of that worker’s salary (typically the last few years prior to retirement, since those are the worker’s highest earning years). This calculation usually includes a ‘salary cap,’ or a ceiling on the salaries used in that calculation. In practical terms, the legislation makes three major changes to Tier 2 city police and fire pension benefits around that calculation and those caps:

First, the bill changes the current salary cap for those workers from $127,283 to $141,408.

Second, it also increases the rate at which that cap climbs over time. At present it increases at the lower of 3% or ½ of CPI-U; this is changed to the lower of 3% or 100% of CPI-U.

Finally, for police officers, the “X of the last Y years” window to determine the pension benefit is modified. At present, benefits are calculated based on the highest 8 of the last 10 years of salaries; this is changed to either 8 of the last 10 or 4 of the last 5 years (whichever is higher).

There are two ostensible reasons behind these changes. The first is that they align Chicago police and fire pension benefits with those that other police and fire retirees in Illinois receive as a result of a 2019 consolidation effort which brought 600+ local pension funds together into two statewide Police and Fire pension funds. It’s worth pointing out, however, that because Chicago’s police and firefighters receive significantly higher salaries than their downstate counterparts, these higher caps will have a particularly pronounced impact on Chicago’s pension liabilities. It’s also worth pointing out that this legislation also doesn’t push Chicago’s police and fire pension pensions into those consolidated funds - beneficiaries get all the reward of the higher benefit levels without having to make any of the concessions that consolidation entails.

The second justification is to help resolve the ‘Safe Harbor’ question regarding Illinois’s Tier 2 pensions. The Civic Federation has a good explainer here, but the gist of the issue is that under federal law, pension benefits which replace Social Security must be at least as generous as Social Security. Because Tier 2 salary caps increase more slowly than Social Security salary caps, it’s possible that in the future we’ll be in violation of that provision.

But this justification doesn’t pass muster. For one, the Safe Harbor issue impacts all four funds, not just Police/Fire; moreover, these benefit changes far surpass those impacting the Safe Harbor issue (all we need to do is adjust the salary cap to match the Social Security salary cap, nothing else). Instead, this legislation increases pension benefits for many workers who won’t be impacted by the Safe Harbor issue *while still leaving the Safe Harbor issue active as a concern for other workers.*

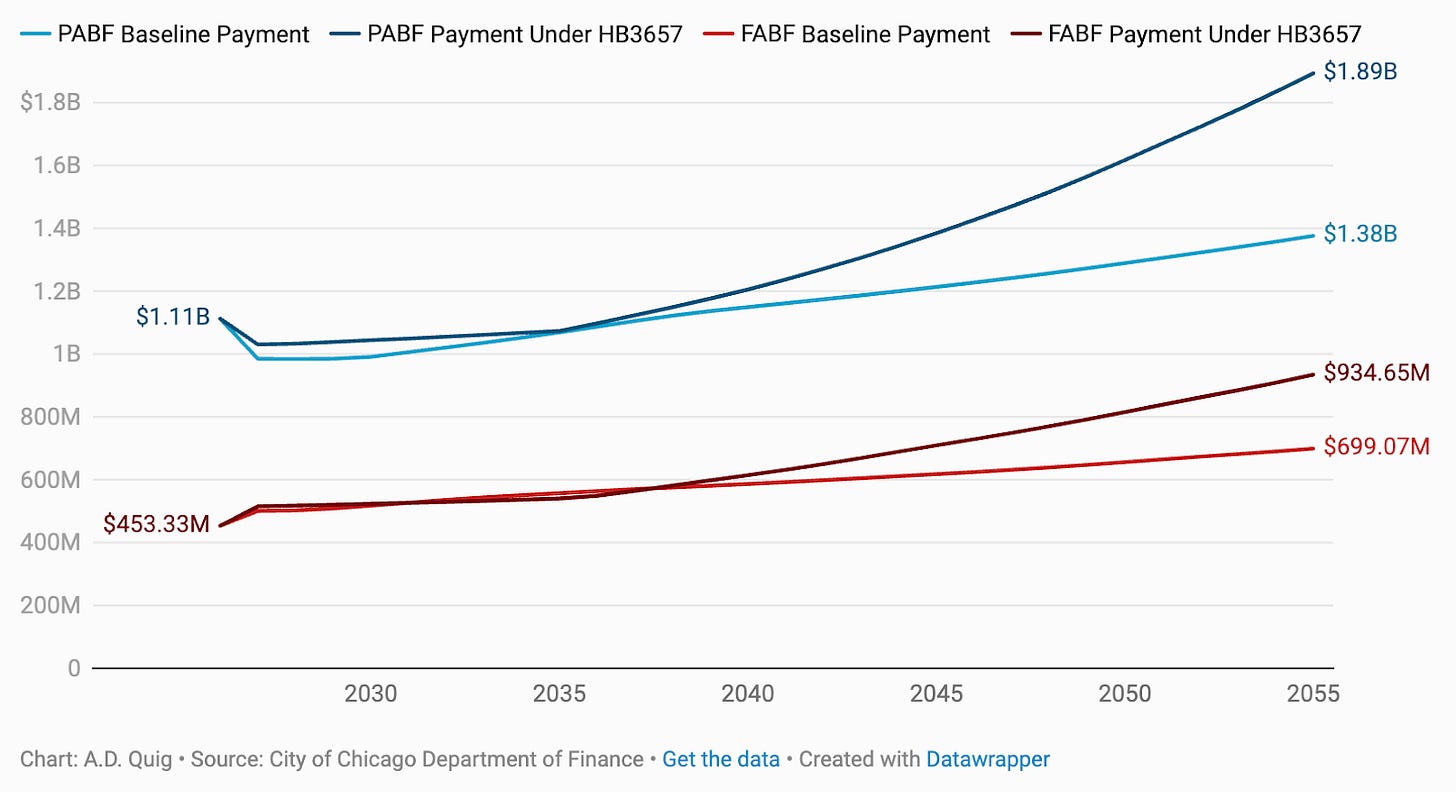

The Tribune’s reporting includes an overview of the practical budgetary impact as provided by the city’s Department of Finance:

Right off the bat, the legislation results in a $60 million increase in the city’s pension payments to the police and fire funds next year. Over time, that number climbs precipitously; by 2055 our pension payment requirements will be over $750 million higher as a result of the change.

$60 million is a big, abstract number, so let’s put that $60 million in better context. The Chicago Firefighters’ Union has been pushing for an extra 20 ambulances to improve EMS response times - a need we’ve emphatically agreed with. Those would cost something like $5 million to purchase and another $11.2 million to fully staff for the year.1 We’ve also argued for more spending on technology to help our police department, like more helicopters which carry a fairly hefty price tag ($11 million for the last one). It’s hard not to imagine this sort of incremental public safety resourcing could get pushed aside as a result of the city being forced to allocate more resources towards larger pension payments. Your opinion may vary, but we’d rather have those extra 20 ambulances and a few helicopters instead.

If you’d rather look beyond public safety, how about social programs like One Summer Chicago, the city’s summer youth jobs program which we’ve previously advocated for? Last year its budget was dialed back to $52 million given the difficulty of the 2025 budget gap; we could zero it out (at great detriment to the city) and still not pay for this pension hike.

We already knew our budget math was going to be really challenging this year. It just got a lot harder. And that’s to say nothing of the fact that the math gets harder and harder in future years as the problem compounds.

How did we get here?

The primary instigator of this bill is State Senator Robert Martwick, a staunch ally of public employee unions who hails from Chicago’s Northwest Side and has never met a pension hike that he doesn’t like. His bill, filed in the last week of the legislative session, flew under the radar as the state legislature attempted to thrash out the budget, energy reform, and the transit fiscal cliff.

Normally, the view of the Mayor would carry a fair bit of weight on any major bill, let alone one that only pertains to Chicago. But Mayor Johnson’s Intergovernmental Affairs team was either unaware or unable to do much to stop it. CFO Jill Jaworski filed a witness slip opposing the bill, but that was about it – no members of the Chicago delegation opposed the bill. And without any opposition from the Chicago delegation, the rest of the state legislature saw little reason to oppose the measure. Ultimately, $11 billion in new pension debt cleared both chambers unanimously in less than a week.2

Then it went to Governor JB Pritzker’s desk. He held it there for two weeks, as civic groups and media outlets started to raise the alarm about the damage this bill would do to the City’s finances. Pritzker acknowledged as much, commenting last week that he was weighing the financial impact on the City of Chicago. But when asked for comment, Johnson still couldn’t be brought to ask the Governor to veto the bill directly.3 Friday, Pritzker signed the bill into law.

You can understand the Governor’s position. Ultimately, this bill is Chicago’s problem. If Chicago lawmakers want to jack up pension obligations, the Mayor doesn’t object, and the state legislature approves the bill unanimously, why should Pritzker have to take a tough veto, just to save the city from a disaster of its own making?

The problem is that Pritzker knows better. By the time the bill made it to his desk, the stakes were abundantly clear. And the Governor has positioned himself as the sane and reasonable check on an inexperienced Mayor who has yet to come to grips with the fiscal or political realities of the office he holds. He’s also been quick to point out his leadership on the state’s fiscal challenges.

Just last year, we wrote that “At a time when so much of city finances - and leadership - remain dysfunctional, it’s nice to see an example of what good public leadership looks like down in Springfield.”

Ouch.

There’s also no easy way to unwind Friday’s decision. The Pension Protection Clause of the Illinois State Constitution states that “[m]embership in any pension or retirement system of the State, any unit of local government or school district, or any agency or instrumentality thereof, shall be an enforceable contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired.”

That means that benefits promised on Friday are locked in, pending a constitutional amendment (and/or a horrifically ugly bankruptcy process). This has already happened once – In 2016, then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel brokered a deal with the unions for greater pension funding in exchange for benefit concessions, but watched the agreement go up in smoke when the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that public employee pensions were constitutionally protected.

A toxic political precedent

As bad as the financial implications of this are, the political implications are even worse. Previously, there had been a shaky consensus that as long as the City and State didn’t dig a deeper hole, we could slowly climb back to full funding. We could blame past leaders (like Madigan and Daley) for these decisions, avoid cuts to existing pension benefits, and slowly grind our way back to a sustainable position.

It’s much harder to make that case now. Not only did the city’s long-term liabilities just balloon, but the police and fire pensions are just the beginning. There are two additional city funds that Martwick and company will argue require a Tier 2 “fix.” Martwick’s also a close ally of the Chicago Teachers Union4, which naturally wants its own “fix.” And honestly, why stop there? If union reps can secure unanimous consent for additional pension sweeteners from Springfield, they’d be crazy not to ask for more.

As long as legislators are merrily digging a deeper hole, it’s hard to imagine any amount of additional revenue or spending cuts that would fix this problem. It’s one thing to ask Chicagoans to gut out tax increases and service cuts to help meet past promises. It’s quite another to ask for that level of sacrifice to make new promises that grow every time the city comes up with more money. What’s the point of finding new revenue to balance Chicago’s books, if it just gets handed out in the form of ever more-generous pension benefits?

What comes next

This is a disaster that will likely take decades to clean up. And that clean-up will require far more political courage and sacrifice than it would prior to Friday. But we try to be solution-oriented around here. And in that spirit, here are a few thoughts for how Chicago will need to react.

First, it should be clear that resolving Chicago’s pension liabilities absolutely must be the next Mayor of Chicago’s number one priority. For example, contract negotiations with the Police and Fire unions need to start with the recognition that union members’ total compensation has already increased substantially. In effect, Tier 2 police and firefighters just saw their pensions increase by a full third. For the city to remain solvent, that needs to be backed out of future wage increases, both in the current CFD contract negotiations, and the next CPD contract which will be back up in 2027. If we’re going to hand-out massive pension sweeteners in between contracts, they have to be offset by smaller wage increases during contract negotiations.

Second, for the foreseeable future, we have to assume that any new revenue will simply get dumped into an ever-expanding set of pension demands. That means the City Council should insist that any new tax hikes be paired with a constitutionally-enforceable pension deal. If organized labor wants more revenue to fund those pensions (and maintain existing city jobs), they’re going to need to be part of a solution to the pension crisis. We’re better off facing this problem now, then grinding through several years of austerity (and more pension sweeteners) and hitting a wall later.

Finally, every elected official we send to Springfield, along with the Mayor, now wears the jacket for Chicago’s pension disaster. Voters need to demand that lawmakers address this issue head-on in upcoming legislative sessions - “stop digging” is no longer an accurate description of reality, let alone a good enough reaction to our problems. And voters will need to ask even tougher questions of electeds in Springfield looking for a promotion. Eight state legislators have already announced campaigns for Congress or statewide office in 2026, and all eight ought to be feeling some heat for their votes to push Chicago deeper in debt.5

If this all sounds like a political nightmare, well, we agree. And we certainly hope that the Mayor, Governor and lawmakers can muster the courage to implement responsible fixes to our pension issues sooner rather than later. But on the current course, the city and state are both in for a world of hurt.

We already did this math here, but this assumes $250k per ambulance, and $70k per EMT/paramedic staffing the ambulance (8 total EMT personnel, since they work in pairs on a 4 day rotation). [Note: a previous and incorrect version of this math mistakenly referenced a 3 day rotation.]

GOP State Senator Li Arellano Jr., the only Republican to vote against the bill in committee, told the Tribune that “I think (what’s challenging) for the Republican caucus is if none of the senators representing the city of Chicago itself had a problem with it, I think a lot in the Republican caucus said, ‘Well, if this is what all of the voices representing Chicago want to do, who are we to disagree with them?'”

Instead, he seemed to imply that the problem was a lack of more progressive revenue. His direct quote: “Absent progressive revenue, it’s impossible to maintain that expectation, so the best way to put it is this is incomplete.”

Another reason that it’s laughable to imagine that the Mayor couldn’t have stopped this if he wanted to. Martwick is a personal friend of Johnson’s, and he’s carried the water for the CTU on legislation before, including co-sponsoring one of the union’s biggest priorities to Johnson’s election: securing an elected school board. Believing that the Mayor wanted to stop this and couldn’t requires believing he got rolled by some of his closest political allies.

In particular, two legislators are running to be the next State Comptroller - the Chief Fiscal Control Officer of the state of Illinois. The irony of that should not be lost on you.

I'm slowly beginning to think that Brandon Johnson may not have been the best option in the last mayoral race.

Nice job on this.