Technology investments for a safer city

Baumol’s cost disease comes for the Chicago Police Department

Here at A City That Works, we’re very much in favor of hiring more police officers. As I wrote a few weeks ago, there’s a lot of evidence that more officers both reduce crime and increase the odds that consent decree reforms get implemented.

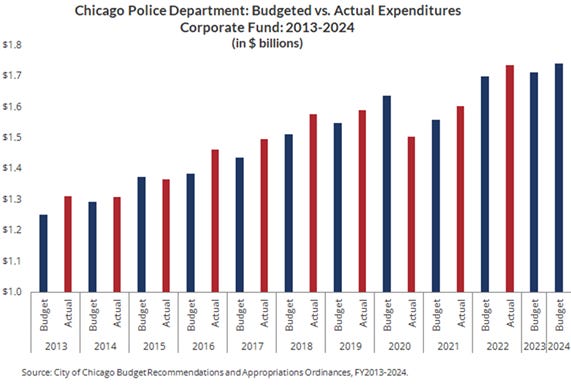

But while critics of the Chicago Police Department are wrong to dismiss the value of additional officers, they are right about something else: policing in Chicago is expensive. As the Civic Federation notes, in 2024 CPD accounted for 12% of the City’s total expenditures. That’s before accounting for pension payments, aligned departments like the Office of Public Safety and Administration, or the alphabet soup of CPD oversight agencies.1 And while CPD expenditures aren’t rising as fast as the city budget as a whole (CPD’s share of the budget was 23% in 1993), expenditures are rising steadily:

Source: Civic Federation

The biggest driver of that increase is personnel related expenses, which are up $424 million between the 2014 and 2024 budgets. But actual manpower is down—total budgeted headcount for CPD has declined from 14,398 in 2014 to 14,137 in 2024. We’re getting fewer officers at higher cost. Over the longer run, these trends are even starker: in the last 30 years, CPD has lost 2,438 budgeted positions, but the cost per CPD employee (the vast majority of which are sworn officers) has risen by 3.4% per year. For context, inflation has only averaged 2.5% per year over the same timeframe.

That difference adds up over time. From 1994 to 2024, CPD’s personnel expenses have risen by almost a billion dollars – from $734 million to $1.7 billion. If they just kept pace with inflation instead, personnel expenses would be a bit over $1.3 billion today. We’d have $400 million dollars to plug pension holes, fund other services, or return to taxpayers.

And there’s not a lot of evidence to indicate that we’re getting more out of officers today than we did thirty years ago. Arrests for major crimes have declined steadily in the last few years – at a faster pace than the decline in reported index crimes.

So what’s going on? Are the taxpayers being taken for a ride?

It’s always possible. But in the last 30 years, the minimum salary for musicians in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra have risen 3.2% -- a rate almost identical to CPD’s 3.4% annual raises.2 I have a great deal of admiration for the world-class musicians of the CSO, but I don’t think they have gotten more productive either. Last I checked, the number of notes in Beethoven’s 5th Symphony hasn’t changed in the last 30 years.3

This phenomenon is not unique to police officers and violinists. As Tim Lee explains in an article for Slate, when some parts of the economy get more productive every year, wages rise. As opportunities in manufacturing, logistics, or other services get more appealing, wages in other parts of the economy have to rise in order to keep up. Police officers may not get more productive, but the alternative career options for a 20-something considering applying to the academy have. The city ends up having to pay more just to stay competitive. As a result, services that don’t benefit from technology-enhanced productivity boosts – like day care, or orchestras, or police officers – get progressively more expensive.

Source: Tim Lee, Full Stack Economics/Slate

This is called Baumol’s Cost Disease, after the economist who first observed it. And it has implications for almost all public services – including nurses at Cook County Hospital, and teachers at Chicago Public Schools. But CPD has emerged as a particular flashpoint, given the size of the Department, calls to defund the police, and the pressures on the City’s Corporate Fund.4

There are certainly non-compensation related actions Chicago can take to make it easier to recruit officers. That includes speeding up the hiring process, providing better working conditions for officers, and doing more to publicly support good officers doing a hard job. But over the long run, we have three choices:

Continue to increase spending above inflation, to increase (or just maintain) officer levels

Keep budget levels flat, and face a slow exodus of officers

Find ways to make our officers more productive

In the short term, it’s absolutely worth hiring more officers, given the well-documented evidence that they improve public safety and help ensure the success of Chicago’s consent decree. But in this environment, any effort to increase headcount will be an uphill battle. And in the long run, we need to get more public safety out of the officers we have.

You can think of two primary ways to make this happen: upgrading the technology that officers use and changing processes to enable them to work more efficiently.5 Both of these are huge topics that I think get a lot less attention than they deserve. Today let’s walk through some potential technology investments. I’ll come back to the management side in a subsequent post.

A wide range of technology needs

Across the full spectrum of police work, CPD’s technology needs are glaring:

Gunshot Detection: This is not the time or place to fight about Shotspotter. But it would be enormously valuable to have a functional gunshot detection system – both to increase the odds of catching perpetrators, and to enable emergency services to save victims who otherwise can bleed out when no one calls 911. But ShotSpotter did more than just dispatch officers – it was a key part of the information fed into the City’s Strategic Decision Support Centers (SDSCs), which serve to coordinate the city’s various crime-fighting tools. Anthony Driver Jr., the Chair of the Community Commission for Public Safety and Accountability, did a great job explaining the process in an interview last year with Fran Spielman:

“Perhaps the thing that hasn’t been mentioned that concerns me the most is those SDSC rooms in each of these districts were built around different components of technology. So you have the pod cameras, you have the license plate readers, you have shot spotter, and I’ve had a chance to sit there and see somebody start shooting. The pod cameras point in one direction now because the person in the room gets a shot spotter alert, which then helps them possibly get an offenders description, to get a license plate, to get other things…

And then that whole system works together. I’m not a tech person. I have no idea what happens when you turn off one leg of that. Do the other two still function as well?”6

The city currently has an RFP out for a new gunshot detection system. I have no idea what it’s going to bring back, but a functional replacement that also helps to coordinate other CPD tools would be a huge asset.

Cameras: The city’s network of POD cameras are another crucial leg of the CPD’s emergency response process, as Driver Jr. noted. But last year, the Tribune and Illinois Answers Project ran a detailed story about challenges with the program: the cameras are expensive, aren’t deployed in the parts of the city with the highest rates of violence, and are infrequently used by officers to solve crimes.7 But cameras can be enormously valuable tools when deployed effectively. The initial Urban Institute study that evaluated Chicago’s original camera deployments in Humboldt Park and Garfield Park found that the program substantially reduced crime and yielded cost savings of $4 for every $1 spent. Meta-analyses of camera programs in the US and globally find benefits to cameras for property and vehicular crimes, but note that effects on violent crime are likely to be much greater with real-time monitoring and response.

Before buying a bunch more cameras, CPD would likely benefit from taking measures to redeploy the cameras we do have, from downtown areas (where there are already a lot of eyes on the street and potential witnesses), to less trafficked but higher crime parts of the city. And as CPD struggles with manpower issues, it’s crazy that we’re using sworn officers to watch cameras in real time. Unless there’s some truly special cases, this seems like a job for civilians. This might be an ideal (and low-cost) job for 18-21 year olds hoping to join CPD, but not yet eligible to join the department.8

CPD Helicopter Source: CPD

Helicopters: Carjackings can take seconds to commit, but if cops do arrive in time or spot a stolen vehicle, they face a terrible tradeoff. If police pursue, high-speed chases can result in horrific accidents that kill or maim bystanders, and leave the city saddled with millions of dollars in lawsuits. But if police don’t pursue, criminals can strike again, and others are less likely to be deterred from the same behavior. It’d be bad enough if this was just a carjacking problem, but as this great Sun-Times interview with an anonymous carjacker notes, these crimes are often used to enable other criminal activity. Once a would-be offender has a vehicle that isn’t their own, it can be easier to ambush rivals or commit other crimes without detection.9

Helicopters are a crucial tool here. They enable CPD to track a fleeing vehicle, follow it at a safe distance with patrol cars, and then apprehend perpetrators when they stop, or the moment is safe. And because a relatively small number of carjacking crews are responsible for much of the violence in the city, it only takes a few successful busts to put a dent in the problem. But during the surge in carjacking Chicago experienced post-pandemic, we only had one-and-a-half functional helicopters. One dated all the way back to 1994 and was regularly down. The other was built in 2006, and neither could fly in bad weather.

The city has made some progress in the last year. The Mayor and CPD were smart to use a portion of the $75 million the city received for DNC security to pay for a new helicopter. We then bought two more last year using Department of Homeland Security funds, which brough the city’s total fleet up to four.10 But Chicago still lags behind our big-city peers: New York has at least 7, Los Angeles has 17, and Houston has 11.

Drones: Drones are a lot cheaper than helicopters, and they may have much wider applications. The first drone as a first responder program was launched in 2017, and more than 1,400 departments across the county now have drone programs. Sending a reconnaissance drone out to calls in advance of an officer has a bunch of benefits. Officers know what they’re rolling into, giving them a better chance at responding effectively and staying safe in the process.

A drone response can also help use resources more efficiently. In Montgomery County, Maryland, 14% of the time a drone response provides information that allows police to avoid sending a patrol car. If we really had our act together, a drone-as-a-first responder program could help strengthen the city’s mental health crisis response program – providing visual confirmation that a situation didn’t require an officer with a gun and a badge, and sharing valuable information with mental health professionals arriving instead.

I sympathize with concerns about privacy, but it’s worth noting that drone operations are subject to the same restrictions on public surveillance that apply to helicopters and officers. CPD could do more to address privacy concerns, such as publishing a time-delayed log of past drone flights (a practice common in other departments). Drones with cameras also provide another layer of police accountability – unlike a bodycam, drone cameras can’t be turned off or pointed in the wrong direction by an officer on the ground.

Unfortunately, as with helicopters, CPD has been a late mover. Some of this can be blamed on the state – Illinois used to have highly restrictive rules on drone deployments, but those were eased in 2023. As of September, the Department only had 5 drones in operation. The Illinois State Police have 75. New York City has 55. Champaign has 6 drones.

Recording-keeping: When an officer does make an arrest, we need to know what happened and why. This data is an important part of understanding how best to deploy officers and can be a crucial tool to identify officers who need additional training (or may be committing misconduct). Unfortunately, CPD uses an “enormous and cumbersome” set of recordkeeping systems that are “filled with inefficiencies,” according to the Department of Justice’s Pattern or Practice Investigation (pg. 124).

In particular, CPD’s CLEAR system includes multiple different modules for recording use of force incidents that don’t talk to each other. If an officer makes a stop that results in an arrest and requires the use of force, they are required to fill out between 3 and 5 forms, all loaded with duplicative information that has to typed up multiple times.11 As of 2018, CPD had a total of 98 different applications to create and store records, across both CLEAR and the separate Criminal History Records Information System (CHRIS), according to the OIG.

This inhibits efforts at reform, because it’s nearly impossible to see who’s appropriately using force when. It’s also a massive waste of time. As CPD’s headcount continues to decline, we’re forcing officers to spend less time on patrol or responding to incidents, and more time filling out reams of duplicative paperwork.12

You can also think of this paperwork as a disincentive to doing actual police work. Nobody joins CPD because they want to spend their life putting cover sheets on TPS reports. The heavier the paperwork burden placed on officers, the less likely they are to get out of the car or stop a suspect in the first place.

I’ve gone into some rather painful detail with respect to use of force, but the recordkeeping issues waste time and degrade performance across the rest the Department as well. The OIG noted that “the Department has no means to effectively identify which records exist for any specific investigation or case.” That sure seems like a problem for a detective trying to figure out if their suspect might be implicated in related cases.

Other Needs: CPD only logs half of the data necessary to measure 911 response times. The Department doesn’t have its own dedicated forensics lab, and the network of state labs have had major challenges with turnaround times in the past (times have improved in recent years).13 As the CCPSA noted in its review of the Mayor’s proposed budget last year, many police stations are crumbling, and far too many CPD vehicles are out of service. And as Driver Jr. noted in his discussion of Shotspotter, it’s critically important that CPD works to link various sources of information, to provide officers and detectives with an integrated picture of what’s happening on the ground.

In other areas, more technology investments may be helpful, but we don’t have enough information about CPD’s current resource utilization. The Illinois State Police have credited Automated License Plate Readers (ALPRs) for assisting in 82% of shooting investigations on expressways in the city (and 100% of fatal shootings). The city has its own program, and as Driver Jr. mentioned, they’re wired into the Strategic Decision Support Centers. I’d bet that additional readers might help with investigations on major thoroughfares and help cut down on vehicle pursuits – but there’s very little available in the public record about the program or whether it would be beneficial to expand it.

How much will this cost?

Because the city provides very limited information about CPD’s non-personnel spending, it’s hard to put a price tag on each of these individual items. Things are complicated further by the fact that a lot of CPD’s IT spending has moved over to the Office of Public Safety Administration (OPSA), which has its own budget, but also provides services to the Fire Department.

But in aggregate, these are not investments that would break the bank. In fact, other departments have managed them with budgets that look a lot like ours today. CPD’s non-personnel spending, which includes everything from IT to horses, accounts for 7% of the department’s budget (10% if you combine CPD with OPSA). New York City spends 8% of its budget on non-personnel expenses. Los Angeles spends 6% of its police budget on non-personnel expenses – or $66 million less than CPD and OPSA combined. While additional spending might be required in some cases, Chicago can do a lot more with the technology and capital dollars that we have today. And of course, in many cases, these investments will result in savings over the long-term, in the form of fewer settlements and better use of our limited pool of officers.14

Investments worth making

It’s interesting that, with the notable exception of Shotspotter, these issues have gotten a lot less attention than debates about police staffing levels. Some of that may be precisely because they account for a much smaller share of the budget. The FOP is also naturally going to prioritize officer headcount and salaries over spending on technology. But if you’re an Alder who cares about public safety, there are clear opportunities to move the needle at limited financial and political cost.

Smart technology investments could make CPD a lot more efficient. They’d also make it easier for officers to do their jobs and stay safe in the process. And over time, they would make Chicago a safer city without breaking our budget.

Namely: The Civilian Office of Police Accountability (COPA), the Community Commission for Public Safety and Accountability (CCPSA), and the Police Board

It’s possible that CSO members could be required to participate in more performances or other functions in the past. A quick scan of the 2024 season program didn’t indicate that, but I’m happy to be corrected on this point.

This phenomenon is also not unique to police in Chicago. Matti Vuorensyrjä observes a similar dynamic with police in Finland. In that study, the only division excepted from rising costs was the permits and licenses division, which got significantly more productive thanks to investments in digital records.

An economist might call these capital and total factor productivity, but I’m doing my best not to put you to sleep here.

The whole interview is worth your time. Driver strikes me as a guy who genuinely gives a shit about the outcomes of these policies, rather than simply performing left or right-wing politics. Likely because of that, he also seems a lot more knowledgeable and thoughtful than any of the advocates on either side of the Shotspotter fight.

In a recurring pattern, CPD comes off in a defensive crouch, while the article quotes other advocacy groups like the ACLU and Electronic Frontier Foundation, who ostensibly criticize the efficacy of the cameras, but also happen to have problems with almost any other technology used by CPD, including drones and license plate readers.

CPD does have a job description for police cadets, which seems close here. But it still requires enrollment in college coursework, which seems outdated given updates to CPD hiring requirements.

It also provides evidence for the theory that lower sentences for juvenile offenders have caused would-be offenders to use kids at higher rates. That’s its own awful problem that I can’t even begin to offer a solution to here. More broadly, I wish more journalism included anonymous interviews with frontline participants in the criminal justice process.

Presumably we retired the helicopter that was *30 years old.*Just imagine being a pilot, chasing carjackers across the city on a dark, windy night in the aerial equivalent of a 1994 Geo Metro.

Those include: An Arrest Report, an Investigatory Stop Report, a Tactical Response Report (logging the use of force), and an Incident/Case Report. If force is used against an officer, and additional Officer’s Battery Report is required.

The defund the police crowd is wrong about a lot, but at least they can point to real budgetary savings from their proposals. Instead, we’ve hit on an approach that has the city paying full freight for officers who we then force to do less and less actual police work.

One of the key barriers? The state’s hiring process, “which can take a year or more.” Once you start looking, you’ll find a talent/hiring issue sitting behind just about every problem in government.

This is also a good example of where a more structured budget process would be helpful. Alders should be asking these questions, and as Conor noted previously, they should have the resources and access to get them answered.

Plus every officer totes a city-supplied cell phone, and the car computers detach as laptops and can be carried along on an interview. The body and dashcams generate big data storage and retrieval fees each month, with a problem being no agency I know can actually afford the staff time to review the images unless something went badly wrong.

Those stats on CPD's record-keeping practices are blowing my mind. That's like four record-keeping system per police district! We definitely need to rework that, that's completely untenable and a huge waste of resources.