How to reprioritize the fire department

Our first responders deserve a fair contract - and the public deserves to have public safety resources deployed effectively.

Programming reminder before diving in: We’ll be hosting our first live meetup next month at the Berghoff on April 10th, from 5:30-8pm! It’ll be a joint event with readers of Slow Boring. You can register here (attendance is free). Hope to see you there!

As of this week, it’s been over 1,360 days - three years and eight months - since the collective bargaining agreement1 between the Chicago Firefighters’ Union and the City of Chicago expired. Since their last deal expired on June 30th, 2021, the nearly 5,000 members of the union - which also covers paramedics and EMTs - have worked without any pay raises or contract.

This is obviously ridiculous. These are dedicated first responders who have a hard job. They deserve to be compensated fairly, and I hope that recent reports about negotiations picking back up are accurate. It’s also worth pointing out that whenever a deal does get finalized, it’ll include a significant amount of back-paid raises for these workers who’ve gone over three years without a deal - and while we allocated some funds for that in the 2025 budget, that expense gets bigger every day that passes without a signed deal.

But setting aside negotiated components like pay raises or benefits, a new contract also presents an opportunity to revisit exactly how our firefighters and paramedics are being deployed - to ensure that the department is meeting city needs as well as it can.

Some basic facts

Let’s start with some basics. The Chicago Fire Department consists of nearly 5,000 personnel consisting mostly of firemen and paramedics, as well as workers in administrative/office positions. Their primary job is to respond to emergency situations, most notably fire suppression/rescue and emergency medical (EMS) response.

Those personnel are distributed amongst 98 firehouses across the City of Chicago. Those firehouses are home to 97 engines and 61 trucks2 which are staffed by firefighters, as well as the city’s 80 advanced life support (ALS) ambulances which are staffed by paramedics. Under current CBA rules3, CFD is required to staff 5 firefighters on all trucks and engines and 2 paramedics per ambulance.4

That’s a lot of manpower staffed at any point in time, and the city doesn’t have much flexibility around it. The current CBA gives the city nearly no flexibility to reduce the number of fire companies5, and only allows for 35 ‘variances’ (instances where the city staffs only 4 firefighters instead of 5 on a given company) per day6. Those two provisions set a really hard floor on city’s staffing requirements. Reporting suggests that those variances are also one of the major negotiating topics of the current CBA, with the city hoping to increase them to 70 per day while the union wants to eliminate them altogether.

It’s also worth noting, I think, what general fire trends look like. While the rates and intensities of forest/wildfires have gotten worse over the past few decades, things look a lot better for urban environments, where home structure fires have become a lot less common. Per the National Fire Prevention Association (NFPA), home fires were down by an estimated 54% from 1980 to 2021, and deaths were similarly down by an estimated 45% over that timeframe:

This is obviously a really good thing! Stricter building codes and improved fire safety regulations (like sprinkler suppression systems in apartment buildings) have come a long way over the past few decades, and we’re better off for it. But that also means that we should be able to devote a smaller portion of our budget towards fighting fires. That’s particularly true if we have other public safety needs - even within the same department - to which we can redeploy those dollars.

We need to improve our EMS response

And those other public safety needs exist. An under-discussed fact about the Chicago Fire Department is that the vast majority of what they do isn’t actually firefighting - it’s medical response, which makes up about 80% of the incidents that CFD services every month:

For the most part, these aren’t incidents where we’re sending trucks or engines with those 5 person crews - they’re incidents where we’re sending paramedic teams in one of those 80 ambulances.7 Resourcing for EMS response - primarily in the form of more ambulances - is another one of the union’s key asks.8

They have a good point. With only 80 ambulances for a city of 2.7 million people, we lag behind nearly all of our peers in terms of resourcing. Here’s a look at the population-to-ambulance ratios for the other top 5 cities in the US, as well as a few other cities I think of as decent comps (larger Midwest or East Coast cities):

Ignoring Phoenix, which seems like a weird outlier,9 the average ratio there is around 22,000 people per ambulance. Chicago’s about 50% higher than that, with a ratio of around 33,000 to 1, which puts more stress on our ambulance force.

That limited resourcing comes at a real cost. Emergency response is a domain where every second counts. Analysis earlier this year from The Trace highlighted the fact that EMS is often not getting there fast enough. The NPFA recommends that departments respond within 5 minutes or less to 90% of medical calls. The Illinois Department of Public Health has a somewhat looser standard of 90% response rates within 6 minutes or less. The Trace’s analysis, however, showed that Chicago EMS is hitting that 6-minute threshold in less than 80% of cases.

It’s not not a new problem, either. In 2013, the city’s Inspector General found that Chicago EMS was meeting that 5 minute NFPA response standard a little more than half the time (in 58% of cases), with response times in none of the city’s 50 wards or 77 community areas meeting breaking 5 minutes 90% of the time. Follow-up reports in 2015, 2021, and 2023 found the same, and that CFD failed to implement best practices to monitor these times, either. It’s also worth mentioning that the 2021 report included an acknowledgment from CFD on the “importance of department-wide quantitative performance measures” and that they planned to work with the city’s Office of Budget and Management (OBM) and Department of Human Resources (DHR) to hire data analytics staff. In what will come as no surprise whatsoever to frequent readers of this Substack, in the 2023 report CFD noted that they were unable to hire those analysts because “multiple requests to OBM for the allocation of budget resources to create a data analysis position ha[d] been denied.”

All of this is to say - our response times are a problem! And not a problem in the way that, say, longer wait times for people in line at the DMV are a problem. The EMS events in that 3-year chart above include nearly 10,000 gunshot victims, 13,000 pedestrians stuck by cars, 39,000 overdoses, 20,000 stroke victims, 69,000 people with chest pains, and 67,000 unconscious people (19,000 of whom weren’t breathing). Getting there faster isn’t about convenience; it’s about life or death.

A cost-neutral approach to public safety

Given all that, it’s not just reasonable to ask for more ambulances - it’s an imperative for the city. Getting us in line with the 22,000 to 1 average from that table above would require around 120ish ambulances in total (a 50% increase to our current 80). The firefighters’ union is a lot more modest than that. They’re seeking another 20 ambulances to put us at an even 100, bringing our population-to-ambulance ratio around 26,000-1. I’d argue that’s too modest an ask, though it would certainly help improve our EMS response times across the city. It would also, of course, cost money. I understand some of the funds for these ambulances to be coming from the mayor’s infrastructure bond which passed last month. While that’s a solution, it’s not the one I advocated for; moreover given that I specifically argued that should find offsetting spending cuts to pay for that infrastructure spending, I think I kinda ought to do that.

Let’s ballpark the expense we’re trying to cover here. In a WGN story last fall, Chicago Firefighters’ Union President Pat Cleary suggested that the cost of a new ambulance at between $180,000 and $250,000. That seems to gel with other estimates I could find online. Use $250,000 to be safe, and 20 new ambulances translates to a $5 million expense for the city.

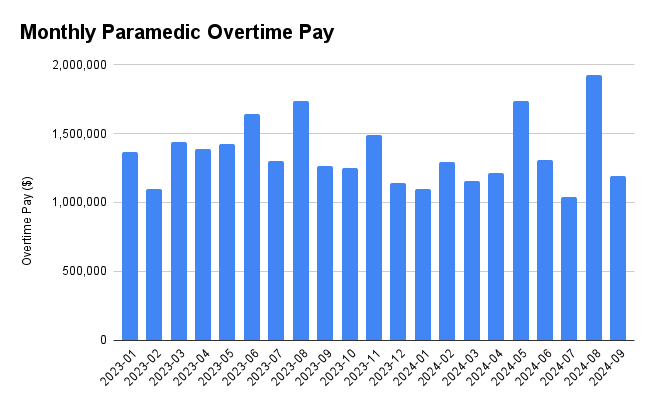

In that same article, Cleary also pointed out the easiest place to find significant savings for the city - our overtime spending on paramedics. It’s quite significant, averaging over $1.35 million per month since 2023:

We’re also relying on overtime far more heavily for our paramedics than we are for firefighters. Between January 2023 and September 2024, 19% of all pay to paramedics was for overtime; over that same period, only 9% of firefighter pay was for overtime.10

Okay, now here’s a little math. City overtime is generally compensated at time-and-a-half, meaning if you replace an employee working overtime with one working normal time, you decrease your overall labor cost by one-third. With that in mind, imagine that we were able to fully staff all paramedic shifts. That would eliminate our monthly $1.35 million in overtime payments, which would be replaced by around $905,000 in normal earnings, generating around $450,000 a month in savings per month. That pays for nearly two ambulances a month! Even if we can’t go that far, just getting our paramedic overtime rate down to that 9% figure we have for firefighters would generate over $200,000 in monthly savings. There’s something here, if we can just figure out how to adequately staff our paramedic positions.

The really obvious solution is to redeploy firefighters.

As I referenced earlier, around 10% of all Chicago firefighters - 275 or so11 - are also cross-trained as paramedics. My understanding is that those firefighters are generally staffed to a truck or engine company (not to an ambulance), but are still trained to help on an ambulance when they’re short staffed. To state it plainly: the Chicago Fire Department should reassign as many of these firefighter/paramedics permanently to an ambulance company as is necessary to ensure we have adequately staffed all ambulance companies - including the new companies created by purchasing 20 additional ambulances.

Doing this would generate meaningful overtime savings for our paramedics, and furthermore enables us to staff those new ambulances without a net increase in labor cost (we’re not hiring net new paramedics; we’re redeploying firefighters from an engine onto an ambulance). We also definitely have enough manpower here to really make a difference; per city data we have about 645 paramedics or paramedic I/Cs; adding those 275 firefighter/paramedics to the EMT force would represent a 40% increase in manpower. That’s big!

Now the controversial part

You may have thought about the fact, however, that if we shift these firefighter/paramedics over to ambulance staffing, we leave a bunch of vacancies on engine companies they just left. That’s true. This is the controversial part, but I want to be explicit about this - I don’t think we should fill those vacancies. Doing so would eliminate the savings we’re using to pay for more ambulances, and then we’d be back to square one on the financial challenge here.

Instead, because fire safety in Chicago has gotten better, but emergency response has not, we should be comfortable redeploying resources from one challenge to the other. Chicago has real financial challenges, so we can’t just throw money at our problems - but we have to maximize every dollar we do spend. That means fewer bodies to fight fires and more bodies to staff ambulances, because that’s the best way to save the most lives.

There’s a practical question of what that should look like, too. The easiest version is probably just relying on those negotiated daily vacancies the City is looking to expand; 35 vacant firefighting positions every day can be the equivalent of 17 staffed ambulances every day. My impression, however, is that variable staffing like that probably isn’t super great for the companies themselves - it’s nice to have some predictability about the number of teammates you’ll be working alongside every day.

Another case can be made for a more statutory reduction in the number of firefighters assigned to fire suppression at all times. The current CBA requires CFD to staff five men on all fire apparatus at all times, except for those aforementioned variances. While that’s consistent with some other cities, like New York, that’s actually a higher standard for staffing than the NFPA’s standard, which recommends a minimum of four personnel on each apparatus. Some previous analyses from the Inspector General’s Office highlighted the potentially significant budget savings of shifting to that four-person standard; as of 2012, they estimated the city could save up to $70 million per year by using four-person crews on all fire apparatus. Given that the average budgeted firefighter salary is up about 26% since then, it stands to reason that those savings would be close to $90 million per year today. While I’m not sure I’d advocate for staffing every company with only 4 personnel, it does seem reasonable that a city with as diverse building construction as Chicago can stand to see more variety in our staffing requirements - the personnel required to fight fires in neighborhoods made up primarily of single-family homes is probably lower than that required to fight fires in high-rises. In practice, a higher number of variances could have the practical impact of allowing CFD to lower a significant number of companies to four-person operations.

On the other hand, my understanding from talking to people who have fought more fires than I ever will is that doing the job with a short-staffed company is very hard. I’m sympathetic to that - which is why it seems worth considering whether we should eliminate a few engine companies and redistribute their firefighters to other companies, to deal with these vacancies while maintaining five-person companies throughout the city. Fewer companies would also help us deal with some of our maintenance-related issues a bit better, since we’d have fewer aging firehouses to upgrade and fewer trucks to maintain or replace (and spare trucks available for use when needed).

None of this is easy. I’m sure the Firefighters’ Union would prefer to add headcount instead of reshuffling it, and Alders will have a tough time swallowing station closures in their wards. But hiking property taxes, incurring more city borrowing, or cutting other city services to cut are painful too. This is an approach that would protect existing CFD jobs and ensure we’ve got fiscal space for raises our firefighters deserve. It would our emergency response services and save more lives. And it would do so while minimizing the long-term price tag for the city as a whole.

The Bottom Line

The City of Chicago has an obligation to use our public safety resources as best we can. Let’s not ignore an opportunity to rebalance the CFD and better address emergencies in Chicago.

Specifically:

Chicago does not have enough ambulances and is not fast enough on emergency response. We need to buy more.

We can pay for those ambulances by cutting back on paramedic overtime spending.

We can reduce or eliminate overtime spending by reassigning firefighter/paramedics from fire duty to ambulance duty.

We should not backfill those positions within fire duty. The city should seek to expand its daily variance allowance to deal with those expected vacancies, or seek to reduce the number of engine companies accordingly.

This leaves us with more emergency response capability and less fire suppression capability. That is a good trade.

We’ll reference this CBA repeatedly today - so here’s a link.

Brief aside: Trucks (or ‘ladders’) are the larger department vehicles which handle search and entry, rescue, and most anything involving a ladder. Engines are the somewhat smaller fire vehicles which handle getting the firehose hooked up to a hydrant and pumping water to extinguish the fire.

The expired CBA remains in effect until a new CBA is passed.

Pages 78-79, Section 16.4(A)(1) and 16.4(B)(2) of the CBA.

Section 16.4(A)(3): The number of fire companies shall be maintained and continue to be maintained at no less than those levels maintained on March 1, 2006 (for example, ninety-six (96) engine companies, sixty-one (61) truck companies, four (4) squad companies, two (2) HazMat units, the Fire Boat, and no less than three (3) Command Vans as well as the number of battalions on said date).

Section 16.4(D)d.1(b)

To the extent an ambulance is not immediately available, CFD will instead send a fire company for more immediate response. This is helped by the fact that the vast majority of firefighters are also cross-trained as either EMTs (about 85% of all firefighters, by my count) or paramedics (another 9%), so they are able to provide immediate medical response in lieu of the ALS ambulance crew.

It’s worth repeating - the same public union represents both firefighters and paramedics. What’s more, around 275 firefighters - about 10% of all Chicago firefighters - are fully cross-trained as paramedics.

And which has pretty abysmal response times - see this ABC15 story from last March highlighting an average 11 minute wait time.

Relegating the details to a footnote: from Jan 2023 to Sept 2024 city payroll data shows a total of $149,897,954.11 in pay to CFD employees with ‘Paramedic’ or ‘Paramedic I/C’ titles, and overtime pay made up 19.02% of that amount (or $28,516,509.33). Over the same time period, CFD employees whose titles were ‘Firefighter’, ‘Firefighter-EMT’, ‘Firefighter-EMT (Recruit)’, or ‘Firefighter/Paramedic’) received $545,906,991.18 in pay, and $51,468,992.56 (or 9.43%) of that was for overtime compensation. City dataset here.

Next up on the CFD beat: single stair building codes, and right-sizing their fire engines and trucks....

An errata note: Where your sentence starts (In a WGN story last fall,) about ambulance costs it appears to link to a Notion page and not a WGN story