CPS’s many challenges, Part 1: Pensions and Debt

Other parts of Chicagoland government have great big fiscal challenges, too!

While we’ll have to wait until this fall for the city’s budget season, throughout this summer the Chicago School Board is dealing with its own budget and the many difficulties it involves. I thought it’d be useful to walk through the many challenges the district is facing (both financial and otherwise). We can start with its long-term obligations: pension liabilities and debt.

The current state of things

Let’s start with some basics. We’ve talked before about the city’s four pension funds. CPS teachers have their own fund - the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund (CTPF) - which CPS, not the City of Chicago, is responsible for. Similar to the city’s four funds, the CTPF is not in great shape. As of today, the fund is 47.5% funded, with a total unfunded liability of about $13.9 billion. By law, CPS is responsible for getting the fund up to 90% funded by 2059, and making the payments necessary to reach that level is one of the biggest budget challenges the district is dealing with. Pension payments to the CTPF made up roughly $10.3% ($1.02 billion) of last year’s total CPS budget.

Separately, the school district also has a lot of bond debt. As of June 30th, CPS has roughly $9.1 billion in outstanding long-term debt. Servicing this debt is also a significant challenge; debt service (interest and principal payments) took up $817 million, or 8.3%, of last year’s budget. It’s also worth note that this debt is relatively expensive: CPS is currently rated non-investment grade (or “junk rated”) by all three major ratings agencies.1 As we’ve discussed in other contexts, lower bond ratings translate to higher interest rate, which means a higher borrowing cost for the district. That is particularly true when those lower ratings are actually non-investment grade, which precludes many larger investors from being able to invest in a borrower’s bonds.2

How we got here

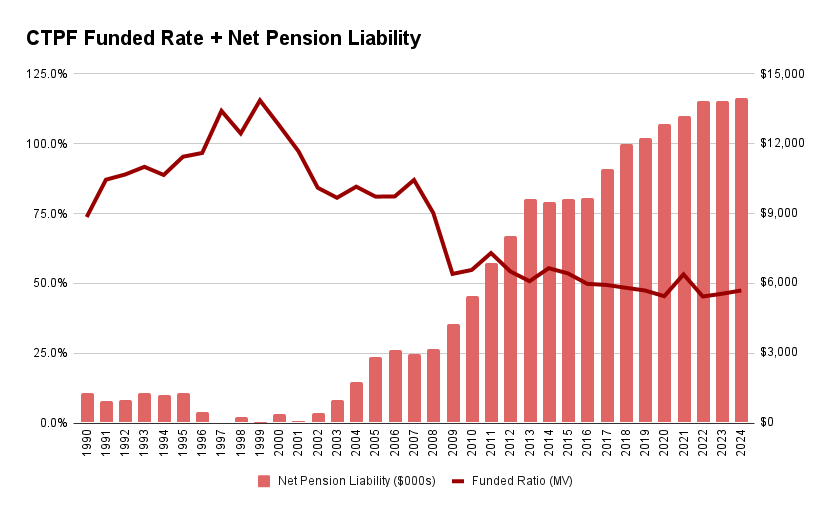

Now let’s talk about the path to these figures.3 Here’s a look at the CTPF’s funded rate and net pension liability over time:

In the early 1990s the fund was doing reasonably well. We started the decade with a 73.8% funded ratio. Notably, during this time CPS was under the purview of the School Finance Authority, an entity created by Springfield to provide fiscal oversight for the district in the aftermath of CPS’s financial crisis in 1980. Control over CPS returned to the Mayor’s office in 1995. In 1997, a legislation change allowed CPS to avoid paying into the pension fund while the fund was at least 90% funded. This created the concept of ‘pension holiday,’ and meant that for the later part of the 1990s and early 2000s CPS basically didn’t have to pay anything into the fund. The healthy funded ratio persisted only because of strong investment returns.

That pension holiday is usually seen as the initial source of today’s issues. In many ways that’s fair (skipping payments is bad), but if investment returns are strong enough to keep the fund adequately capitalized, the fund is still adequately capitalized. The real problem was that once the fund fell below 90%, they didn’t actually make the payments sufficient to true up the fund back to that 90% level. Instead, we were only contributing a fixed portion of payroll each year (not an amount tied to our normal cost or any increase in the net liability). That amount was woefully inadequate to actually fund the system.

Asset declines during the 2008 financial crisis then caused an even larger drop in the funded ratio. Instead of CPS making the correspondingly larger contributions in the wake of that to get us back on track to a reasonable funded ratio, from 2011 to 2013 Springfield instead granted another partial holiday. The district was allowed to make significantly smaller payments ($187 million instead of $600 million in 2011, for example) for several years. We’ve basically been treading water since then, with much larger payments now necessary as we continue the climb towards 90% funded by 2059.

And then there’s the debt side. The story here is a bit simpler I think, though it’s also not been covered as much as the pension problem. The simplest version is that throughout the 2000s, the CPS budget was consistently balanced in part by issuing debt. Some of this debt was to finance capital projects4, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. What is a bad thing, however, is the fact that this debt was often backloaded or extended via ‘scoop-and-toss’ borrowing, where existing debt is refinanced into longer term debt with a slower amortization schedule (meaning the payments made each year are smaller, but the debt remains outstanding for longer). That can get pretty vicious over the long run; imagine a capital improvement that’s good for about 10 years before you have to renovate again financed by debt that you only pay down over 30 years. By the time you’ve paid off the debt from the first project, you’ve had to finance two more rounds of improvements.

There are a lot of other components which have made the problem worse, including some funky financial engineering5 which we shouldn’t have gotten into, but the reality isn’t that complicated. We just kept borrowing too much and kicking the can down the road instead of more sustainably addressing our capital needs over realistic time horizons.

Who pays for CPS pensions?

As with any other pension fund, CTPF contributions can be split into employee and employer contributions. Those contributions are made by three distinct sources: CPS itself, the CPS teachers themselves, and the State of Illinois.

On the employee side, CTPF members are required by law to contribute 9% of their salaries as the employee contribution into the pension fund, which came to around $269 million for the 2025 budget. But despite the name, that doesn’t all come from the employees; beginning in 1981 CPS agreed to a ‘pension pick-up’ of 7 percentage points of the 9% for employees, leaving the employees themselves to contribute just 2% of their actual salaries into the fund. Under the terms of the CTU’s current collective bargaining agreement, this continues today for any teachers hired prior to 2017, while teachers hired after them contribute the full 9 points. Given the current mix of active employees, that pick-up increased CPS’s pension expense by about $135 million last year.

The employer contributions are then split between CPS itself and the State of Illinois. Since 2018, the ‘normal cost’ - the amount that the fund’s liability increases from active employees accruing another year of benefits - has been funded by the State of Illinois. As of last year that was around $354 million, or 35% of the total employer contribution for FY2025. The remainder - around $662 million - is the payment needed to help amortize down our past underfunding issues (to get us back to 90% funded by 2059). That’s the employer contribution CPS is obligated to make.

It’s worth noting that the share paid by CPS is a lot bigger than the share that any other school district in the state of Illinois has to make. All other Illinois public school teachers are members of the Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS), and TRS employer contributions largely come from the State of Illinois, not from individual school districts6; according to the Civic Federation 97.1% of employer contributions into TRS for 2025 came from the state, with local districts contributing only 1.3%. In contrast, CPS is on the hook for nearly two-thirds! This is weird.

One particular thing to point out about that weirdness is that if you live in Chicago, you’re effectively paying for two sets of teacher pensions; our property tax revenue largely pays for CPS contributions, but our state income and sales tax payments subsidize those TRS contributions for the rest of the state’s school districts. Those in the suburbs and downstate, on the other hand, mostly only pay for TRS.7 Again, that’s weird, and it doesn’t strike me as particularly fair.

Non-teacher pensions

Our focus so far has been on the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund, which, as the name suggests, is the pension fund for CPS teachers. But CPS has many non-teacher employees too. Most of these are covered by a different fund - the Municipal Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund (MEABF), which we’ve covered before as one of the City of Chicago’s four funds.

By somewhat of a weird quirk in Illinois law, CPS is not legally required to make the employer contributions for these employees - the City of Chicago is. On the face of it, that strikes me as kind of absurd. The city doesn't actually employ these workers. The city doesn’t set their salaries. The city doesn’t negotiate with their union about anything related to their benefits or compensation. And yet they’re the ones on the hook for pension payments. Setting anything else aside, that just feels… weird?

Historically this didn’t really matter, because Chicago and CPS were effectively separate legal entities ultimately controlled by the same elected official (the mayor). The revenue raised to make those payments is also coming from the same set of taxpayers (Chicagoans) and the city also has broader ability to raise revenue from various forms of taxation, so on the margin they have more ability to make those payments. But that ultimate legal control is now changing, as we shift towards a fully elected school board. Consequently, the issue of who pays for non-teacher pensions has become a larger issue. Under Lori Lightfoot, an intergovernmental agreement between the City and CPS set the district on a path towards paying the full MEABF payment with a gradual ramp-up; as of last year CPS was supposed to make a $175 million payment into the fund. Whether they would follow through on that obligation (and whether they should do so by taking out a high interest rate debt) was a big part of last fall’s drama regarding CPS CEO Pedro Martinez and the school board.

I understand why CPS is reluctant to take the burden. They aren’t legally obligated to do so, and their budget math is hard. As a matter of common sense, though, it seems obvious to me that they should pay this going forward. Ultimately these are CPS employees, not city ones. Moreover, as the Civic Federation has covered in detail before, there are plenty of other financial entanglements between the City of Chicago and CPS which the city could look to unwind if the district chooses to play hardball on this. The city subsidizes capital improvements to many schools, waives water and sewer bills on CPS properties, provides waivers for permitting fees, and determines the annual TIF surplus revenue amount which is distributed to CPS. To be clear, the city very much needs to have a successful school district, and I don’t think it behooves the public to have the two entities wage a contentious fight over every line item back and forth. But these things will need to be worked out one way or another. If CPS is intended to be independent, they really ought to be independent.

How do we fix this?

So, there’s your overview of our long-term pension and debt challenges for CPS. Sorting out exactly what to do about it is going to take a long time, but here’s a general start:

Stop Digging. The first and most basic step is not to make things worse. It’s promising that last fall the CPS board rejected the Johnson administration’s proposal to take on an additional $300 million in borrowing to close their budget gap. That’s the kind of easy short-term option which leaves us worse off in the long run, and it’s the kind of thing we need to reject going forward.

Bring down our borrowing cost. Debt service makes up over 8% of the CPS annual budget. If we can refinance our outstanding debt into a lower interest rate8, that number gets lower. But despite what some figures might claim, we can’t just “go to Jamie Dimon at Morgan Chase and tell him to renegotiate”; it doesn’t work like that. Instead, there are two real ways the district ought to target our borrowing cost. The first is getting our fiscal house in order so we can get our credit rating upgraded. CPS is rated BB+ or its equivalent by the big three ratings agencies, and that comes at a real penalty to our borrowing cost, particularly because we’re below investment grade. Jumping up just one step, to BBB-, would likely result in a much lower interest rate for the district. We need to ensure we’re having conversations with the rating agencies about what exactly they’d need to see for the district to get upgraded, and then to do those things.

The second, and perhaps more interesting path, is with some kind of financial engineering. As the Civic Federation recently covered, when CPS went through a financial crisis in 1980, the creation of the School Finance Authority (SFA) gave the district access to bond markets again because an entity perceived by the market as a more responsible borrower was able to be the borrowing entity. Even if you don’t want to go that far, there are other ways to structure our borrowing that would likely result in a higher issuer bond rating. The City of Chicago’s Sales Tax Securitization Corporation (STSC), for example, is rated AAA by Fitch and is able to issue bonds at a much lower borrowing rate than the city is because its legal structure gives it (and its bondholders) a senior claim to the city’s share of state sales tax revenue. The state also provides a variety of revenue sources to CPS, too, like the district’s share of personal property replacement taxes (PPRT) and of course its Evidence-Based Funding (EBF) allocation. These revenue sources are already largely used to support debt repayment - the CPS budget website refers to “‘Alternative Revenue’ GO bonds” backed by these precise sources - but if CPS could set up a bankruptcy-remote entity similar to the STSC which had a first claim on some of these revenues, that entity would likely be able to borrow much more cheaply than the district itself does today. It’s worth thinking about.9

Sharing the burden. This is a fancy way of saying “get somebody else to help pay for it,” which generally isn’t particularly popular with those somebodies. That said, there are a few cases I think worth making, beginning with that weirdness around the State of Illinois paying for all TRS employer contributions but only a third of CTPF’s. The most straightforward way to change that - and one that’s been proposed by former State Senate President John Cullerton, as well as education nonprofit Kids First Chicago - is to merge CTPF into TRS, creating one consolidated pension fund for all Illinois teachers. I imagine getting Springfield to take on an extra $600 million in pension payments next year would go over like a lead balloon, so the details are important here - probably a phasing in over time, coupled with some elements of more state oversight (similar to how the state’s been considering rescuing our transit agencies) seem like a reasonable pitch, particularly considering that this would involve removing a weirdly onerous requirement from CPS, rather than giving CPS something special that nobody else gets.

In a smaller consideration, I also think CPS should considering ending the pension pickup that CPS still makes for Tier 1 employees. Nearly half10 of active employees covered by CTPF are Tier 1, and for those workers the district is still paying the bulk (7 of the 9 percentage points) of the employee’s contribution share into the pension fund. My understanding is that that pickup is not a constitutionally protected benefit; it’s just something that gets negotiated in the CBA. As such, we can’t change this until the next round of contract negotiations take place (the existing deal runs through 2028), but it should be on the table for those negotiations.

The only other final group that could take on more of the burden is the public, if CPS wanted to pursue more revenue options. Realistically, though, CPS’s local revenue options are pretty limited. The district’s main locally controlled revenue option is its property tax levy, and annual increases in that levy are capped at the lesser of CPI or 5%. Since CPS already makes those increases on a pretty consistent basis, any further increases would be subject to a public referendum, and I’m skeptical of how that would go over, particularly now that half the board is elected rather than appointed. Outside of that, realistically any other revenue options have to involve Springfield in some way. The main call we’ve consistently seen is for the state to increase EBF funding - though I think we’d be far better off focusing on a CTPF/TRS merger to more directly address our pension payments.11Operational Efficiencies. This is the hard part. Like many other parts of Chicago government, inefficiency is simply a luxury that CPS is no longer able to afford. We’re going to need to figure out how to do more with less. Exactly what that will require is a deeper conversation for another post, but I think Chalkbeat’s really excellent deep dive into the district’s underutilized schools provides a pointer in the direction we’ll have to go.

The bottom line

Pension liabilities and debt problems are not just a city issue; they are very much a big deal for Chicago Public Schools as well. It’s imperative that we figure out an actual path towards resolving our long-term financial challenges, and be honest about how hard it’s going to be. But if we’ve learned anything from CPS’s challenges over the last few years, it’s that we can’t afford continue to kick these problems down the road.

See Table 1 here; as of June 30th CPS is rated BB+ by Fitch, BB+ by S&P, and Ba1 (equivalent to BB+) by Moody’s. It’s worth mentioning that we are rated BBB - which is investment grade - by Kroll, a newer ratings agency whose ratings typically appear to be a bit more generous.

As a basic example: insurance companies, which are very some of the most common and frequent large investors in fixed income and municipal bonds, are broadly governed by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC). The NAIC sets regulations on how much of an insurer’s portfolio can be in medium- or low-grade securities (BB is equivalent to an NAIC “3” rating, which is “medium”). State regulations set similar laws; here in Illinois for example insurers cannot have more than 20% of their portfolios in ‘medium and low grade investments’ (per 215 ILCS 5/126.23).

As a quick note: for more detailed information on the history of Chicago pension issues (and the CTPF in particular), I implore interested readers to check out Amanda Kass’s excellent blog, as well as Daniel Vesecky’s more recent coverage on pensions and the SFA at the Civic Federation. Both great resources!

Unlike the city, CPS capital spending occurs in the same budget as its operational spending.

While I really don’t think it’s the crux of our problem, I do enjoy this stuff enough to give it my best Matt Levine impression in a footnote:

Throughout the early 2000s CPS got involved in some structured debt issuances known as ‘auction-rate securities’ (ARS) which purported to lower the district’s borrowing cost under good market conditions. Effectively, rather than issuing debt at a fixed interest rate, these securities involved monthly or weekly auctions in which investors could ‘bid down’ the rate they were willing to lend to CPS, creating the opportunity for CPS to benefit from improved market conditions (or from an improved perception of their own creditworthiness).

The ARS market then tanked during the 2008 crisis, when nobody wanted to lend to anyone, and these securities reverted back to their ‘failed auction’ rate, where CPS was on the hook to pay a higher interest rate to bondholders (in the event that the auction was unable to generate sufficient interest at a better rate).

Compounding this unfortunateness, CPS also had decided to hedge out that floating rate benefit they were receiving via interest rate swaps, in which they would receive a floating rate and have to pay a counterparty a fixed coupon. This basically converted their floating rate ARS back into a synthetic fixed-rate debt. The upside of doing this is to try and lock in a lower rate of borrowing than they’d achieve via vanilla fixed rate debt. Among other things though, one of the main downsides is you can’t really refinance a synthetic debt the way you can refinance vanilla fixed rate debt - they’re just stuck on the hook for these larger interest payments unless you terminate the swap, which can be rather expensive.

Finally, one note I really want to stress: the above is a fun sexy story - and there is really good coverage on it from the Tribune back in the day, which is worth reading! - but it is very much not the ultimate source of our CPS debt problems. At most, we’re talking about an incremental few hundred million dollars of payments as a result of this ARS nonsense. That made things worse, but it’s like blaming the cherry on top instead of the ice cream sundae itself.

Though I will note that many - but not all - other school districts also have some form of ‘pension pick-up’ where the local school district pays the employee contribution.

I say “mostly” because, again, the state does cover around 35% of CPS employer contributions, so those in the suburbs aren’t literally paying nothing towards CPS - but that’s still *a lot* less than what Chicagoans are doing for TRS.

That “lower interest rate” bit is very very important! If you’re not refinancing to lower borrowing cost, but instead just adjusting principal repayment to pay down your debt more slowly, we’re not making things better - we’re just resorting to the scoop-and-toss problems which caused this mess in the first place, and again trading a win today for a bigger loss tomorrow.

To push back on my own suggestion, there’s an interesting question here about how segregating off one of our largest funding streams like this would impact CPS’s overall GO rating. If CPS has a more junior position on that source, isn’t any non-securitized debt more risky, and wouldn’t that make it harder to get upgrades? It’s a fair question. My first thought here is that if we have a new, AAA-ish way to issue bonds for the district, our overall bond rating matters less, so that’s still worth doing, but it is a fair question to ask.

Table 10 in the CTPF’s latest annual financials here show 15,424 active Tier 1 employees and 17,665 active Tier 2 employees, so that’s 46.6% Tier 1.

Among other elements, it’s important to remember that EBF impacts every school district in Illinois - so increases to EBF would have a pretty watered down impact on Chicago in particular; only about 20-25 cents of every incremental dollar in state funding would go to CPS.. In contrast, a CTPF/TRS merger would have a direct impact; 100 cents of every incremental dollar in state funding there goes towards helping CPS’s bottom line.

Money stuff readers of Chicago unite! Great overview of a thorny problem; I just finished Forrest Claypools Daley show which had a small aside as to why the pension holiday existed - very useful in big 2025, where it seems like an awful idea

IIRC, the issue with CPS having to pick up those pension payments was part of the deal that was struck for mayoral control of the schools - which was also unique in the state.