The State of Chicago Pensions

The past, present, and future of our greatest public finance challenge

Now that we’ve got some of the basics down on pensions, let’s take a look at Chicago’s pension systems themselves.

The City of Chicago is responsible for four distinct employee pension systems. These are the Police, Fire, Labor, and Municipal Funds.1 None of the four are in particularly good shape today. Experts generally recommend a pension fund be something like 80% or more funded to ensure adequate liquidity on an ongoing basis; the best funded of these four (the Laborers’ Fund) is around 45% funded, with the others in the 20-25% range. Because the Laborers’ Fund is also the smallest, the combined funding ratio of the city’s plans is only 23.8%. That is bad. Very, very bad.

The Past

How did we get here? Fair question. Here’s a look at the funding ratios of the four funds on an annual basis since 2001, per Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research:

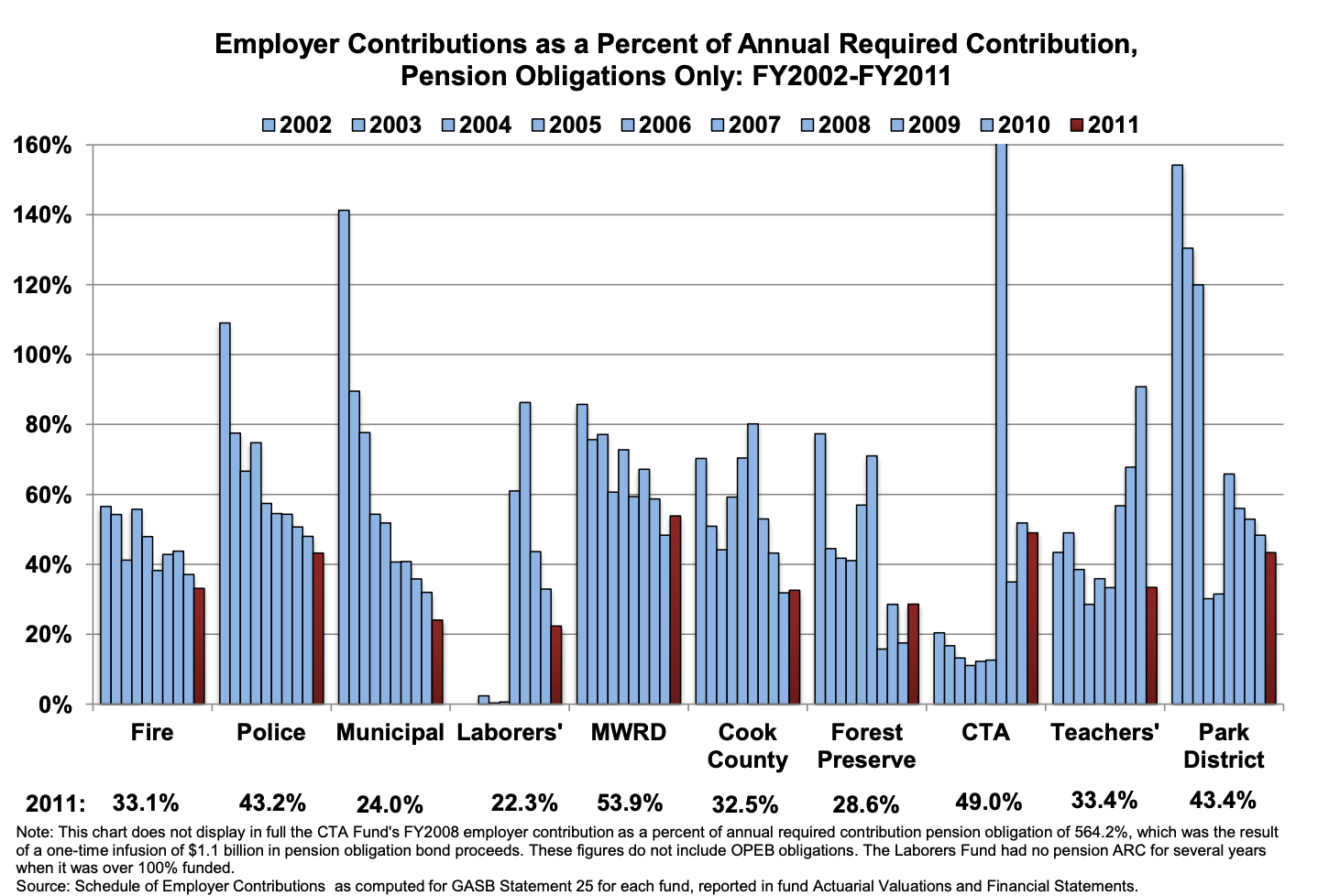

As of the early 2000s, we were actually doing pretty okay. The Firefighter and Police Funds aren’t great - both are below 80% - but the other two are quite healthy, and the city’s combined funded ratio is above 80%. Over the following decade, however, we dropped off a cliff. Growth of pension liabilities dramatically outpaced growth in assets, driven in large part by inadequate contributions by the city. Here’s a look (from the Civic Federation’s 2011 report on local pension funding) at employer contributions from 2002 to 2011 for the four city funds (plus other city/county entity funds):

As we discussed earlier, the right way for an employer to set their contributions is to determine how much liabilities grow in a year, net out asset returns and employee contributions, and close that gap. Chicago did not do that. Their contributions were fixed as a multiple of employee contributions, which is how the Firefighter’s Fund could go a full decade without employer contributions ever being even 60% as high as they should have been. The Police and Municipal Workers’ Funds only had one year of sufficient contributions, and the Laborers’ Fund even had several years of no contributions at all, thanks to a city policy that didn’t require any contribution whatsoever while a fund was over 100% funded.

By the 2010s the situation had gotten bad enough for the city to start trying to fix things. In 2010 a new law created the “Tier 2” definition of employees, which reduced pension benefits for those hired after January 1, 2011. In 2014 Mayor Emanuel rolled out a variety of additional reforms aimed at shoring up the system, including some increases in property taxes, increases in employee contributions, and a reduction in the annual cost of living adjustment (COLA) to retirees. These reforms were then struck down by the Illinois Supreme Court in 2016, on the grounds that the state constitution forbids any reduction in an employee’s pension benefits whatsoever. Back to the drawing board.

This was then the impetus for the city to finally start making its contributions on an actuarially-calculated basis (the way you’re supposed to!), instead of using a multiple of employer contributions, with the goal of getting the systems back to 90% funded over the following 40 years. To help smooth the transition to this new system, the city used a ‘pension ramp’ where their contributions would climb to the actuarially number over five years. For the Police and Fire Funds, these ramps ran from 2015 to 2019; for the Laborer and Municipal Funds, they ran from 2017 to 2022. Consequently, as of now the ramps are finally done, and the city’s contributions are finally set based on an actuarial and liability-based estimate, with the goal of 90% funded ratios in 2055 and 2058 for the two groups, respectively. Notably, these contribution levels are enshrined in law, which means they can’t ignore the problem even if they want to. I don’t know how else to work this in, so this feels like a good time to mention - for more information on the history of funding challenges the city’s faced - as well as a whole bunch of other public finance information - I can’t recommend DePaul professor Amanda Kass’s blog enough.

The Present

That all takes us to today, with the overall system sitting at around 24% funded. We’re finally making the contributions we need to be. What does that look like? Here’s a fun chart from the Civic Federation’s review of the 2023 city budget:

The city’s total budget for 2023 was $11.8 billion. Pension contributions made up roughly $2.7 billion - or 23% of total city spending. That’s worth stating a second time: about a quarter of the city’s budget is going towards pension payments. That’s a big share of the budget - and a lot higher to what we’re used to, as you can see from the above.

To be a bit charitable, it’s worth noting that the $2.7 billion includes a $242 million supplemental pension contribution that the city was able to make thanks to better than anticipated revenue growth in 2022 - which is both a great use of funds and not something that’s statutorily required. Netting that out puts the “Required Pension Spending” at just under 21% of the city’s budget. But that’s still over a fifth of the budget, at a time when we continue to face a number of other issues as a city, from public safety to education and everything in between. I say this to point out that as great as it is that we’re getting the problem under control, we are in no way out of the woods.

Where did this money come from? A few dedicated sources go to different specific funds, but here’s a look at the overall revenue sources for each and the four combined (based on Civic Federation data):

Property tax revenue is by far the largest source, making up just over half of the overall fund (and over 75% of the total revenue for Police + Fire). Another one-sixth comes from the city’s corporate fund (the general fund for any government spending), followed by reasonably significant contributions from the Enterprise Fund and Water/Sewer Taxes as well.

Another trend I want to highlight is the ratio of active employees to beneficiaries in each of these funds. This is basically a look at how many employees are paying in versus getting paid out every year. Again, from the Center for Retirement Research:

As of today, three of the four funds have more beneficiaries (those getting paid out) than active employees (those paying in). As this trend continues, employee contributions will make less of a dent against the change in liabilities every year - and employer contributions will have to grow further to make up that difference. At the same time, those larger pension contributions threaten to crowd out money for salaries on current employees, which could create a pretty dangerous cycle (fewer employees → fewer employee contributions → larger employer contributions → less money for new employee salaries → fewer employees).

The Future

So we’ve stopped digging a hole, but we still have a long and hard path ahead of us. How do we make this path easier?

Mathematically the only options to reduce the unfunded liability are either to cut benefits (reducing the funds’ liabilities) or continue increasing contributions every year (raising the funds’ assets). Cutting benefits is hard. A cut to the plans’ annual COLA changes seems like an obvious target, but the state Supreme Court has already ruled such a cut - as well as any other potential cuts - unconstitutional, meaning we’d need to amend the state constitution prior to any benefit reductions even being feasible. A constitutional amendment to make that change has been floated before - Rahm Emanuel pushed for it while he was mayor, and some more business-friendly media sources like Crain’s and the Chicago Tribune have made the case for it - but I’m pretty skeptical of that happening any time soon. Emanuel is obviously no longer mayor, and Brandon Johnson’s deep roots in the teachers’ union suggest he’s not looking to make cuts anytime soon. Governor Pritzker - who’s probably the one guy clearly strong enough to overcome any political blowback from the unions if he wanted to do this - has previously referred to such an amendment as a fantasy. The only feasible “change” to the liability side of the equation I can see happening is some kind of plan consolidation - where Chicago’s pension funds get rolled in with other state pension funds, which should lower management costs (but not actually the pension liabilities themselves). While I think it’s a reasonable and good idea - and one that might happen - that’s no silver bullet.

That leaves the asset side, which means higher contributions. As a reminder, the city’s contributions are set by law, so they can’t ignore the problem even if they want to. For contributions to go up, we either need to make spending cuts to other government services or raise revenues. Mayor Johnson has previously stated a commitment not to raise property taxes (as of today, it’s still on his campaign website), which - if true - means hiking the largest current revenue source to the plan is off the table. Against that backdrop the city’s been looking for more creative revenue sources - like approving a new casino estimated to bring in roughly $200 million a year in revenue for the city, already earmarked for pensions.2 That’s only 9% or so of the total contribution the city has to make this year - but assuming (granted, yes, that’s a big if) those estimates pan out, that’s 9% more than we’d otherwise have.

The $242 million supplemental pension contribution made this past year by the Lightfoot administration highlights another small step in the right direction on pension policy. Any time a government runs a surplus, it has a strong temptation to find something to do with that money. Maybe it’s some fancy public works project that’ll generate a lot of attention and headlines. Maybe it’s a new pilot program that somebody has cooking up. Whatever it is, it is imperative for the City of Chicago to resist those urges. Setting those funds aside to help dig us out of our pension debt is absolutely the right decision. One of Lightfoot’s last acts as Mayor was an executive order creating a “pension advance fund” of around $640 million from budget surpluses to go towards further supplemental pension payments in the future - and the incoming Johnson administration has already indicated they may roll this back. That is a bad idea, and a step in the wrong direction on the most important public finance issue the City of Chicago faces.

Finally, the last chance we have to improve things on the assets side is growth. This isn’t an easy lever to pull; in may ways it’s the most mercurial and hard to control. But more growth - both of economic activity and of population - means a larger economic (and tax) base to draw from, which means more money coming into the system. Illinois has had some pretty famous out-migration issues in recent years, and while the last census showed Chicago adding around 50,000 residents since 2010, we’re still down versus 2000, and not growing as quickly as we should. Whatever we can do to reverse that - fostering a stronger job market, remaining an attractive destination for immigrants, improving our schools, or lowering taxes3 - is important.

The Bottom Line

This is again largely more explanatory than advocative, but if I can leave you with any takeaways I hope it is these:

Chicago has very real and very deep pension issues

We are finally making progress towards fixing them, but there’s still a long road ahead

The road is a hard one. We’ll need to get creative to find palatable solutions going forward

You may be asking yourself why teachers aren’t included in this list. While there are a number of entanglements between the City and Chicago Public Schools (a topic for a future day!), the Chicago Board of Education is the entity responsible for the teachers’ pension fund, not the City of Chicago. Other school workers, however - like crossing guards, bus aides, and other support staff - are covered by the Municipal Fund.

As part of the approval process, Bally’s (the casino operator) also pledged $40 million as an up-front payment to the city, which went towards the pension funds this year. You can see those funds going towards the Police and Fire funds in my table outlining the 2023 sources of revenue for the four plans. Technically this also means a $200 million annual revenue source would only add $160 million relative to today’s contributions, given that the $40 million is non-recurring.

I am obviously cognizant that suggestions like improving the quality of schools (which probably takes more spending) or lowering taxes, while potentially conducive to more long-term population growth in the city, also directly impact our budget in a way that directly cuts against the goal of freeing up spending for pensions. This is yet another difficult aspect of our great challenge.