Last week, ratings agency S&P downgraded the City of Chicago, lowering our general obligation (GO) bond rating from BBB+ to BBB. This wasn’t particularly unexpected, considering that they had placed the city on negative watch in November of last year1, but it’s not good, and it’s a notable indication of how the city is viewed in public markets. I think it’s worth walking through what the downgrade means for Chicago.

A brief explainer

Chicago, like most other municipalities (and other governments) has a fair amount of debt. This debt is held by investors. Those investors like to compare the riskiness of the various entities they lend to; riskier borrowers require a higher interest rate to offset the risk. To make comparisons easier, ratings agencies (the big three are S&P, Fitch, and Moody’s) score borrowers and assign them a credit rating intended to encapsulate the strength of a borrower’s financial position.

As we noted in our scorecard, most of Chicago’s peers have very strong ratings. Sticking with S&P, both New York City and Los Angeles are currently rated AA. Our surrounding Midwest competitors are generally quite well-rated as well: Minneapolis and Columbus are both AAA, and Indianapolis, Cincinnati, St. Louis and Milwaukee all range between AA+ and A-.

Chicago’s downgrade from BBB+ to BBB stands in stark contrast. While BBB is still considered ‘investment grade’, it’s near the lowest end of the IG spectrum. For context, of the fifty largest cities in the United States, the only other S&P BBB-rated city is Detroit, which is just ten years removed from the largest municipal bankruptcy in the history of the United States. That’s not exactly a mark of confidence in our fiscal position.

The practical impact

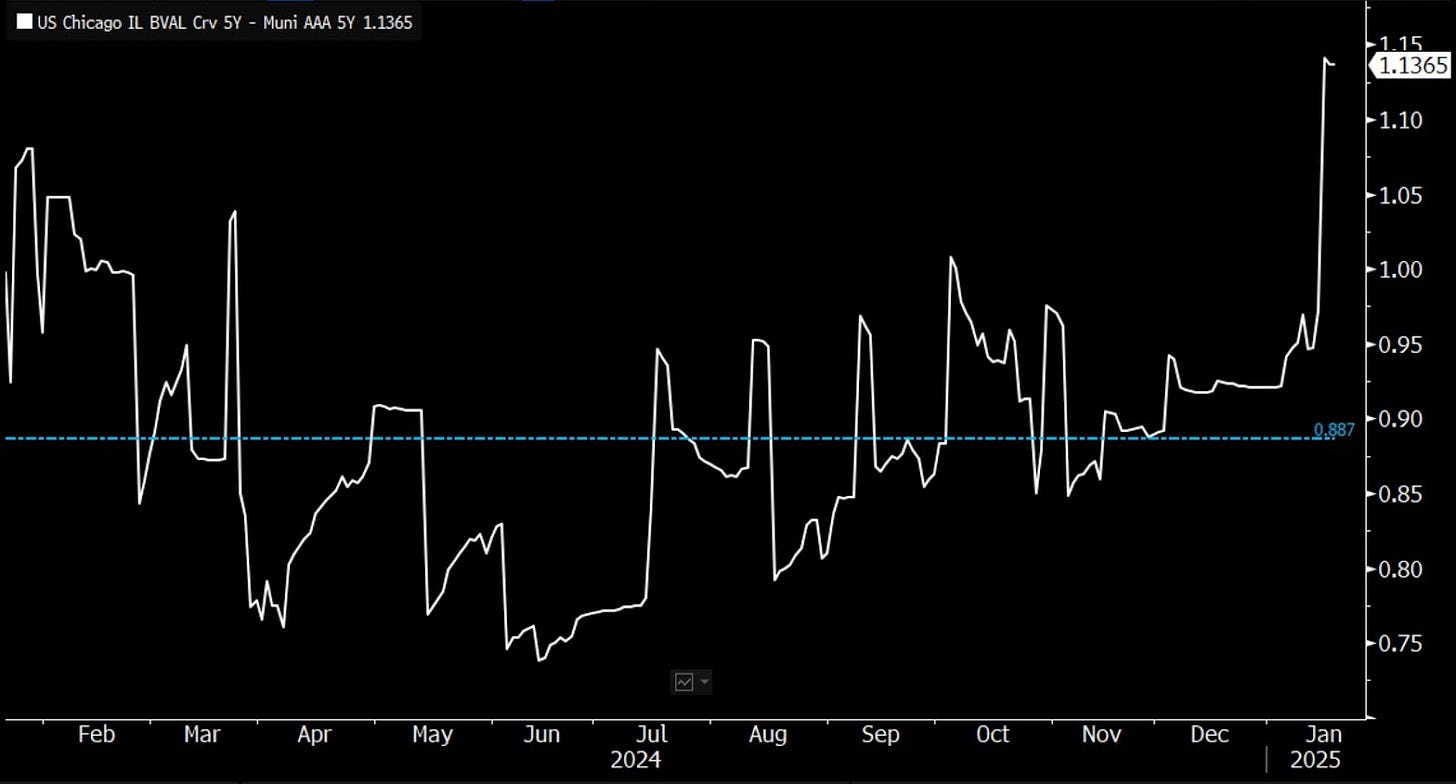

Beyond the symbolic significance, let’s talk about the actual practical impact. As I mentioned before, investors require a higher interest rate from worse-rated borrowers to compensate for the extra risk. Per Schwab, for example, as of last month BBB-rated borrowers were being charged around 0.85% more relative to AAA-rated municipal borrowers. Moving from BBB+ to BBB translates into a higher cost as well.2 From Bloomberg, here’s a look at the risk premium charged on Chicago bonds relative to AAA municipal bonds over the past 12 months:

That spike on the righthand side of the chart? That’s what happened immediately after the S&P downgrade - our borrowing costs got about 20 basis points higher. For context, that’s about an extra $2 million in annual debt service for every billion dollars in debt issuance - simply because we fell from BBB+ to BBB at one of the three ratings agencies. Further downgrades could incur a much larger incremental cost as well, especially if we start talking about a move into non-investment grade (BB+ or lower) territory3.

It’s worth noting that while Chicago already has very significant levels of debt issued, that downgrade won’t change anything about the interest we owe on that debt; the coupons are already fixed at the time of issuance. What we’re talking about here is a higher interest rate required on future debt issuances for the city. A few examples:

The $1.25 billion housing and economic development bond we approved last year to replace our TIF-driven development system hasn’t actually had any issuances yet. This just made those issuances - and, consequently, made city-driven development projects - more expensive.

While they’re getting more and more infrequent given the macro interest rate environment, periodically over the past few years we’ve been able to refinance older city debt at lower interest rates, generating long-term budgetary savings for the city in the process. That just became a lot harder to do going forward.

Though I don’t think we should really be doing much general borrowing going forward - again, we already have a significant amount of debt to deal with - any new borrowing has just gotten more expensive.

Beyond the concrete impact on our borrowing cost, there’s also a broader impact on investor confidence in Chicago to consider. I’m not just talking about investors in our debt. When businesses are choosing where to expand their operations, they have to consider the environment in which they’re operating. A city’s fiscal situation is part of that. If we want to attract more businesses and investment in the city - and we should, because growth matters - we have to take that into account.

Let’s stop making bad decisions

In their report, S&P highlighted the inadequacy of our 2025 budget outcome - and the structural deficits the city should expect going forward as a result - as the main reason for the downgrade:

The downgrade reflects our view that the 2025 budget leaves intact a sizable structural budgetary imbalance that we expect will make balancing the budget in 2026 and outyears more challenging," said S&P Global Ratings credit analyst Scott Nees. The rating action also reflects our view that following the 2025 budget negotiations, the city's practical options for raising new revenue appear less certain, as does the willingness of city leadership to cut spending, creating a level of uncertainty around its financial trajectory that is more appropriately reflected in the lower rating.

While it’s nice to feel vindicated, the more important takeaway here is that we really truly do need to get serious about spending. S&P isn’t a partisan organization. They don’t care about scoring political points or making the mayor look bad; they are as close to an objective evaluator as you can get on Chicago’s fiscal outlook. When they say that our structural budget gaps are an impediment to our fiscal position which we need to deal with, they mean it - and we should take them seriously.

Given all that, I can’t help but find it incredibly bizarre that one day after the S&P downgrade announcement, the mayor’s office went ahead and filed a proposal for a new $830 million bond issuance for the city. I’m not really clear what the purpose of the new debt is. The filing refers to public infrastructure, though the proposed ordinance also lists a wide array of purposes, including funding judgments and litigation settlements against the city. It seems pretty strange to me that these infrastructure investments weren’t rolled into the mayor’s budget proposal last month in any capacity. I also haven’t seen any news or press releases or stated purposes in less legalese language from the mayor’s office. That makes it quite different, in my mind, than an issuance of the housing and economic development bonds we approved last spring4.

All of that makes me very skeptical that this is really just an attempt to issue debt in advance of next year’s budget fight instead of, yet again, looking into ways to cut structural spending to close our future budget gaps. Assuming an interest rate of around 5%, an extra $830 million in debt translates to over $40 million a year in increased interest payments (to say nothing of any principal repayment) in every subsequent year until that debt is paid off.

To put it plainly: The solution to closing next year’s gap cannot be to make every subsequent budget year’s deficit worse. That’s exactly the kind of practice the S&P downgrade is warning us against. Let’s not ignore it. This $830 million borrowing proposal is a bad idea, and City Council should reject it.

Per S&P, a negative watch implies at least a 1-in-2 chance of a rating being lowered in the next 90 days.

A somewhat technical aside: it’s also worth mentioning that S&P is currently the middle of our three ratings from S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch (we are still A- at Fitch, and Baa3 - equivalent to BBB- - at Moody’s). Many institutional investors will pay particular attention to a borrower’s median rating, so the S&P downgrade has a particular significance on our borrowing cost.

Slightly deeper explanation: a move into non-investment grade territory would have a particularly pronounced impact on the actual buyer base of Chicago debt, since many institutional investors are ratings constrained and are unable to buy (or have a much higher target return for) non-investment grade debt. Consequently, a move into non-IG territory wouldn’t be one more linear step to our borrowing cost; it’d very likely be a much, much more pronounced spike in our borrowing cost.

Further - I’d note that those housing and development projects are also ‘paid for’ in the form of an increase in corresponding property tax revenue coming in from expiring TIF districts, while this issuance lacks any explanation of how things would be paid for beyond general city revenues.

Thank you for putting this together. You do a great job of putting succinctly in writing what I often struggle to convey. Public finance can be esoteric, but sound practice in this space so important to good governance.

Recognizing that S&P is a non-political, analytical organization, it would behoove them to dumb down these analyses so that the mouth-breathers at city hall understand what a pickle they're in. The CTU very obviously lacks any semblance of financial literacy, and need to be spoken to as such.