This infrastructure bond is a bad idea

Weird backloaded debt deals are bad, even if the projects they fund are good

Later today, City Council is set to vote on Mayor Johnson’s $830 million bond proposal which has become the source of some controversy. A variety of important figures, including Ald. Bill Conway (34th) and State Comptroller Susana Mendoza, have weighed in against the proposal. While I am just a guy with a newsletter, I thought it’d be worth sharing my view as well.

Good debt is still debt

Let’s start on a soft note: as a general rule, it is totally reasonable to finance infrastructure projects with debt. These are typically projects that produce public assets which endure for several decades, and it makes sense to amortize that cost over the lifetime of the assets. Debt is not in and of itself a bad thing, if it allows you to build or acquire something of greater value.

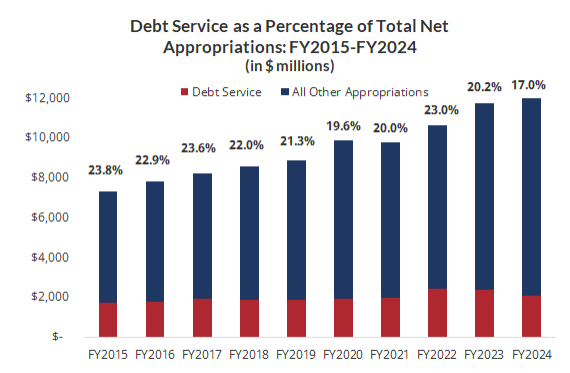

But there’s a limit to that. Even if a series of debt issuances are individually justifiable, they can still produce an aggregate result which isn’t. I wrote last month about S&P downgrading Chicago from BBB+ to BBB and why that was bad for the city. We now have the worst1 bond rating of any major city in the United States and are too close for comfort to junk bond status. While S&P’s statement didn’t specifically call out our level of debt, they did cite our structural budget imbalance going forward as the major reason for concern. That imbalance will only get worse if we incur further debt and have to allocate an even larger share of our budget to debt repayment (we’re already devoting roughly 20% of the city budget to debt service).

We also know this isn’t the only borrowing we’re trying to do this year - we just passed the Housing Bond last year, and the City has previously indicated they’d like to issue the first $250 million tranche in 2025. Our city enterprises (O’Hare and the Water/Sewer systems) are also expected to issue project bonds as well per the latest Capital Improvement Program (CIP).

Repaying that debt is going to make our budget harder. We saw how much a knife fight it was last fall when our budget gap was $982 million. It’s only getting uglier, and city government has shown no appetite for making the kind of spending reforms that would free up resources to fund that debt service. They need to. Just because the CIP lives outside of the annual budget process doesn’t mean it’s irrelevant in how we should think about the city’s resources.

The reality is that debt service for all that debt has to come from somewhere, and we’re running out of somewheres. Chicago’s capital expenditures have typically been funded by bonds, and those bonds have been historically financed through property taxes. But our existing property tax levy is primarily being devoted to our annual pension payments, and last budget cycle showed us how little interest there is in increasing that levy. It behooves us to figure out how to get serious on spending reforms to ensure we have adequate resources to service our bond debt (or to find other non-debt ways to fund our capital projects).

And weird debt isn’t good debt

Speaking of debt service, let’s talk about the structure of this deal. As I mentioned before, it makes sense to amortize the cost of an asset over its lifetime. This deal doesn’t do that. Instead, for the first two years the city doesn’t make any interest payments at all; they instead capitalize the interest2, resulting in a higher principal balance and consequently higher interest payments in ever year down the road. The structure also doesn’t begin to amortize the bonds until 2045, after 19 years of interest.

Chicago CFO Jill Jaworski defended this schedule on the grounds that our preexisting debt commitments make it difficult for us to repay principal in a nearer term. I’m actually a bit skeptical of that. I don’t have the exact structure, but based on Tribune reporting I tried comparing what repaying this schedule would look like compared to repaying on a straight-line schedule3:

The scenario where we pay off principal and interest from day 1 is not that much more onerous than the backloaded scenario. We’re looking at something like $8-9 million per year more in debt service. But in exchange, we end up paying nearly $400 million less in total lifetime repayment on the bonds, and our ability to service the debt from 2045 onwards is laughably better.

I don’t know if this is a real principle or not, but I tend to get more skeptical about the merits of a proposal the weirder a structure it takes. It’s one of the reasons I thought that shifting from the TIF system (kinda weird and messy!) to the Housing/Development Bond (very straightforward!) was a good idea. That’s not always a hard and fast rule - the Sales Tax Securitization Bonds are kind of weird, but I think they’re really great4 - but I find it’s a good guideline. This one rubs me the wrong way, especially with the two year capitalized interest period up front which ensures no cash outflows until after Chicago’s next election cycle in 2027. That looks a lot like a two-year scoop and toss, and it’s not something that we should be considering.

The Bottom Line

Adequately funding infrastructure is incredibly important. We need to invest in making a city a better place, but we need to do it the right way. We can’t just issue more debt and trust that we can figure out how to pay for it later. If these capital investments are absolutely critical, the City should amortize it on a straight-line basis, and approve an offsetting package of spending cuts to ensure that we aren’t putting any more pressure on the city’s credit rating.

Issuing more - and weirder - debt - can no longer be considered an adequate approach to our capital plans. Our leaders in the City Council should demand to see that there’s a strategy in place before they agree to approve yet another round of borrowing for the city.

Okay, fine - we’re tied for worst (with Detroit).

What this means is that instead of making an interest payment, they increase the principal on the bonds by the same amount. Pretend we had $100 million in bonds with a 5% interest rate (and ignore mid-year compounding). Instead of paying $5 million in interest in Year 1, at the end of the year you just roll it into the principal and now have $105 million in bonds outstanding. At the end of Year 2, you then pay 5% on the larger balance, and if you roll it again you now have $110.25 million in bonds outstanding. Whenever you actually do start paying interest, you’re then paying that on a higher principal balance.

This assumes a 5% interest rate and compares (1) two years of capitalized interest, 18 years of interest-only payments, and 10 years of straight-line amortization to (2) 30 years of straight-line amortization. I can’t stress enough that this is just a back-of-the-envelope thing; I don’t have the actual proposed amortization schedule and my numbers are entirely fictional - but I think they’re probably in the right ballpark.

To elaborate: the STSC is an actual good piece of financial engineering that allows Chicago to borrow more cheaply in exchange for promising bankruptcy-remote protection to bondholders on one particular revenue stream (the city’s share of state sales tax revenue). It does this by creating a middleman (the STSC) which sits upstream of the city with respect to that state revenue stream, repays its bondholders and then passes along the residual cashflow left over after debt service on to the City of Chicago. So long as Chicago does not go bankrupt and never intends to default on its bonds, there’s no downside for the city, since we’d pay those bondholders anyways - but if we pay them first, before the city even touches the money, we get a better rating and a lower interest rate. That’s a good kind of financial engineering magic!

Great column. The city has always done a bond like this , they are called General Onligation bonds. Very routine - which is why this idea is particularly bad. I don't recall such a backloaded structure - except scoop and toss, which the city under both Rahm and Lori, chipped away at until they were eliminated. Talk about going backwards.

This is VERY helpful to understand the stakes of the upcoming vote, thank you.