Vacant: The City of Chicago’s broken hiring process

It takes six months to fill a job in city government—if you’re lucky.

Artist’s depiction of the City hiring process.

Last Monday’s Tribune has an update on a long running city-problem: Officers in the Chicago Police Department spend far too much of their time doing work that could be handled by civilian employees. In 2018 more than 800 sworn officers, trained to carry a badge and a gun, were doing clerical work.[1]

The solution is obvious - hire civilians for desk jobs and get officers back on the streets. Hundreds more trained officers could make an immediate impact on public safety. With more officers, we’d also be less reliant on overtime and wouldn’t have to cancel so many days off. It would also be easier to maintain higher standards for officer conduct if we weren’t so desperate to hold onto the cops we had.

Given that, just about every Mayor tries to civilianize key parts of the Department. None have succeeded. Mayor Johnson’s first budget created 398 civilian positions at CPD, but a year later only 51 have been filled. As the Tribune notes, his efforts have fallen victim to the same challenges that derailed efforts by Mayors Lightfoot and Emanuel before him: a “maze of red tape” that makes hiring city employees an almost herculean task.

The Tribune story is well worth your time. But CPD’s hiring challenges are just the tip of the iceberg. The City’s hiring process is broken across the board. It hobbles city services and raises long-run costs. But it’s also a solvable problem. With a current hiring freeze in place, the Mayor’s Office and key Departments have an opportunity to take stock of the problem and get things back on track.

Help Unwanted

Way back in 2015, the Office of the Inspector General (IG) tried to figure out how long it took for the city to fill a vacant job. It turned out that no one knew. There was no process to track the full timeline it took to hire people, and there were no real goals set around hiring timelines. After digging through a year’s worth of hires, the IG came up with a number: on average, it took six months to fill a job in city government.[2] That’s three times as long as the median large employer, according to 2021 data from the Society for Human Resource Management.

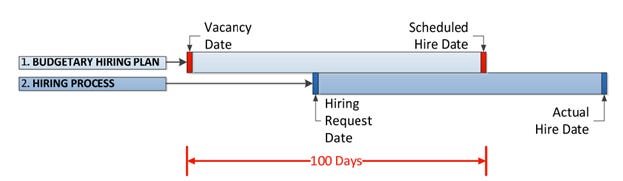

The Inspector General’s Office noted that departments trying to hire talent were caught between two key barriers. First is the Office of Budget and Management (OBM). As part of the budget cycle, OBM works with departments to estimate the number of hires they will need to make over the year, based on their end-of-year vacancies, and estimates the natural turnover that will likely occur. Then OBM and the department build a hiring plan designed to fill those vacancies while coming in at or under budget.

But crucially, that hiring plan is *not* designed such that if the departments hire steadily throughout the year, and the expected turnover occurs, the department will hit its budget. Instead, City Departments are forced to delay new hiring *until* they have conserved enough budget early in the year to guarantee that they won’t go over – even without planned turnover. Then, when the planned natural attrition does occur across the year, the department ends up understaffed and under budget. That works if your goal is to come in under budget: in 2013, the city spent $125M less than it budgeted for in salary expenses. But it does so at the expense of city operations – departments are forced to delay hiring by an average of 100 days.

Source: Office of the Inspector General

That’s not all. In addition to setting up a hiring plan that delays hires at the front of the year to ensure the city hasn’t overestimated turnover, departments have to get OBM to sign off on every individual hiring request they make—again to ensure that they’re coming in under budget. That’s a handoff that takes more time: on average, 18 days from request to approval. OBM also doesn’t do much in the way of communicating its decisions: sometimes department requests remain open, even after OBM has decided against moving forward.

It’s no secret that Chicago is facing major budget challenges. The city just instituted a hiring freeze to address this year’s budget shortfall. But organizations the world over manage to hit budgets without kneecapping their hiring processes. OBM’s approach is the equivalent of driving with the emergency brake on to make sure you don’t get a speeding ticket.

That’s hurdle one. Hurdle two is the actual posting and recruitment process. That’s managed by the Department of Human Resources (DHR), which “had no formal process for recording actual hiring times and was unable to identify specific points of delay,” according to the IG. That’s because the Department of Human Resources doesn’t exist to fill vacancies in a timely manner. The five goals laid out by DHR in Chapter 1 of the City Hiring Plan make no mention of helping departments fill roles efficiently, or ensuring that the city attracts the best possible talent. DHR’s main goal is to avoid getting sued – and specifically to ensure that the city doesn’t engage in favoritism or patronage in the hiring process.

That’s important! Chicago has a notorious history of patronage that’s bilked taxpayers, treated honest applicants unfairly and undermined city services for generations. Hiring didn’t start to really change in the city until a series of 1970s/80s court cases, known as the Shakman decrees, eventually forced a grinding, root-and-branch cleanup under the watchful eye of an independent monitor. The long-running legal battle was a key factor in the demise of machine politics in Chicago.[3]

But the decree hasn’t applied to Chicago since 2014, when a federal court declared that direct oversight of hiring was no longer necessary. The City still needs to maintain strong policies to avoid patronage, but there’s no reason those policies must paralyze city government. Guess who’s in charge of ensuring the city keeps the hiring process clean today? The Office of the Inspector General – the same agency raising alarms about the city’s glacial hiring pace.

So today city hiring is a maze of handoffs between the hiring department trying to fill a position and a Budget Office and HR Department that exist to say no. And each handoff is an opportunity for the process to get stuck. The Inspector General built a painstaking flowchart outlining the standard hiring process. Without a process for tracking timelines or status, every handoff is a chance for the process to stall, leaving a vacancy in limbo. OIG found that OMB rarely communicates when a request to hire is actually denied, leaving Departments waiting for an approval that may never come. And neither DHR or OMB provide any guidance to departments to help them navigate the process.

A best-case representation of the hiring process. Hires requiring special skills, or input from multiple departments (like civilian hires at CPD) may be even more complex. Source: Office of the Inspector General (edited to fit on one page)

The city has also seemed unwilling or unable to make things better. OBM flatly refused to implement suggestions from the Inspector General to implement budget controls that don’t enforce delays and improve communication with other departments. DHR was at least willing to consider the IG’s suggestion to track and set goals for the city’s time-to-hire. But four years later the HR department said it was still trying to find the right technology tool to track hiring times, and there hasn’t been an update published by the Inspector General’s office since. That was in December 2019 – right before the pandemic, rising private sector wages, and a huge influx of new programs to administer all made hiring more challenging for the city.[4]

The result is perpetual staffing shortages:

9-1-1 Calls: The Office of Emergency Management and Communications (OEMC) had 176 vacancies as of last year’s budget, and has a particular shortage of bilingual employees.

Public mental health clinics: The Chicago Department of Public Health has 500 vacancies, and is struggling to hire for the roles necessary to re-open publicly run mental health clinics.

Asylum seekers: At last year’s budget hearing, Ald. Adre Vasquez asked about the possibility of hiring city residents to staff migrant shelters instead of an expensive outside contractor. DHR informed him that that wasn’t even a possibility in the first year, given the city’s hiring timeline.

Uniformed police officers: We’re down almost 2,000 officers from the city’s peak and struggling with a decline in Black officers. But somehow, we still subject applicants to an 18 month testing and paperwork process before they can enter the police academy, according to another OIG investigation.

Public transit: The primary reason your train or bus isn’t showing up on time is because the CTA can’t manage to hire enough operators. Note: as a sister agency, CTA is not subject to the OBM/DHR constraints, but the good people over at the Active Transportation Alliance and Commuters Take Action have highlighted similarly pointless bottlenecks in the CTA process.

Even if you believe that city headcount should be cut dramatically, a broken hiring process still inflicts huge costs. It’s harder to attract high quality talent when applicants have to spend months waiting to hear back from the city. Good people have other options; citing City Hall sources, the Tribune story notes that “by the end of the timeline… many candidates have moved on to other jobs and hiring managers have had to go down as far as their fifth choice.”

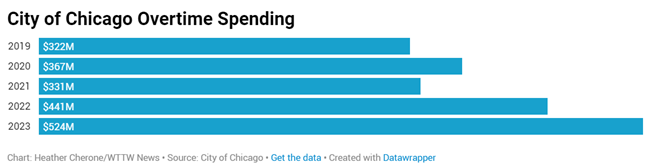

It’s also harder to let an under-performing employee go if they can’t be replaced for at least six months. Staffing shortages can mean costly overtime, up since 2019, or reliance on contractors or other third parties to do jobs that the city can’t fill in a timely manner. And every hour that managers spend filling out paperwork and fighting with DHR is an hour that they aren’t spending on their day jobs.

Credit: WTTW

This is a solvable problem, and thanks to this hiring freeze, the relevant personnel at OMB and DHR should have some time on their hands. What better chance to hammer out some solutions?

The city can start by fully implementing the suggestions that OIG made almost ten years ago. Those include:

Eliminating planned hiring delays at the beginning of the year (OMB)

Setting clear expectations with departments about how long hiring processes will take (OMB and DHR)

Improving communication about when hires are approved or rejected and why (OMB)

Setting goals and building a tool to track time to fill vacancies by city department (DHR)

But while those improvements are a starting point, I doubt they’ll be enough to solve the problem. Even if the city eventually does launch a unified platform for candidate tracking and reporting, the process will still be incredibly complex and managed by two departments that exist to say no. The city should take this opportunity to dramatically cut down on the number of steps and hand-offs between OMB, hiring departments and DHR. A simpler process would move faster, be easier for OIG to audit, and be much easier to encode in an applicant tracking system.

By the same token, simply throwing more bodies at a process problem is a temporary solution at best. DHR added a bunch of headcount last year, likely in an effort to speed up the hiring process. This might help for a little while. But it’s far more expensive than just getting the process right (now all those new hires are sitting around with nothing to do during the hiring freeze). And in the long run, the headcount expansion just creates a larger institutional bureaucracy at the city with the ability to say no.

Truly fixing these problems will require redesigning the hiring process to ensure it preserves fiscal and patronage checks with a minimal number of handoffs. Here are a few options to consider:

Eliminate in-year OBM approvals: Once OBM approves a Department’s hiring plan at the beginning of the year, that Department shouldn’t require any more approvals to follow that plan. If we’re worried that Departments will go over budget, hiring plans can be scheduled around the vacancies open at the beginning of the year, and departments can be given automatic authority to fill new openings as a result of turnover, at or below the prior salary levels. Departments that still somehow managed to go over budget would face budget cuts in the subsequent year. OBM personnel would then be freed up to handle other tasks, or to be able to address urgent off-schedule hiring needs (such as responding to Covid-19, the migrant crisis, etc.).

Create a flexible pool of Shakman-exempt positions: Exempt hires move much more quickly through the system, but are limited to a very specific set of titles. But reality is messy – a department may need to make a couple of crucial hires that don’t fall on the list and do so fast. Allowing departments to designate a small percentage of their non-exempt headcount (say 5%) as ‘exempt’ could create critical flexibility without opening the floodgates to patronage.

Devolve DHR responsibilities to departments: Human Resources liaisons who work in the departments actually trying to hire absorb the culture of the department they work in and are accountable to the colleagues they sit next to. They also have a better understanding of the department-specific needs. The centralized Department of Human Resources should exist for two reasons: managing centralized processes with large economies of scale (applicant tracking systems and background checks) and ensuring Shakman compliance (signing off on lists of qualified applicants). Every other step should be under consideration either to be eliminated outright or handed over to the hiring departments. That includes drafting position descriptions, compiling hiring packets, and sending offer letters.

Hold ‘on the spot’ hiring events: Same day hiring events give candidates the opportunity to interview, drop a resume, and receive a job offer conditional on passing a background check. At the state level, the Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) consolidated its 12-step hiring process and is running these events successfully across the state. It’s also much better hiring experience for candidates, and a great option when Departments need to hire at scale (paging the CTA).

Hiring is not the only place where red tape is strangling government. Experts nationally have started to raise the alarm about a crisis of ‘state capacity’ that is paralyzing the public sector’s ability to function. Solving these problems will require going beyond general concerns about red tape, and digging into the layers of burdensome, risk-averse process that are slowly paralyzing the city. Getting hiring right would be a good start—and would help give the City the talent and flexibility to start hacking away at a whole host of other problems.

Key takeaways:

City hiring is a mess, and it’s affecting everything from our ability to hire cops to social workers. In the process, we’re driving up costs (thanks to overtime and outsourcing) and weakening core city services.

The key causes of the problem are risk aversion and neglect on the part of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and Department of Human Resources (DHR)—which operate at cross-purposes to the departments actually trying to deliver city services.

To fix the problem while still maintaining necessary budget and legal controls, the city should stop delaying hires at the beginning of the year to account for planned attrition later, remove OMB’s authority to signoff of individual hires mid-year, and eliminate or de-centralize many of the key hiring steps currently managed by the Department of Human Resources.

[1] We’re also an outlier relative to other big cities. CBS found that civilians made up 6% of Chicago’s police department, but 22% of the LAPD and 35% of the NYPD.

[2] That’s horrifying, but it’s also a very conservative estimate: Many positions remain vacant for more than a full calendar year, and vacancies open prior to the start of the year are ‘zeroed out.’ So the data for positions filled in 2013 doesn’t include how long those positions were vacant in prior years. It also excludes sister agencies, the Mayor’s Office, and the Chicago Police Department (more on that later).

[3] Also Cook County and the State. We owe Michael Shakman an immense debt of gratitude.

[4] In subsequent DHR hearings, Department heads have occasionally referenced improvements in time to hire, but those are sporadic and don’t necessarily correspond to improvements in the overall hiring process. There was no reference to time to hire metrics in the most recent DHR budget hearing though, and OIG hasn’t published any recent updates indicating DHR has figured this out. I also reached out to DHR for comment weeks ago and didn’t hear back.

Another great article team! One question about this though: the post frames CTA hiring as a city process, but my understanding is that as an independent government authority hiring undergoes a different process there. Do they deal with OBM and HR the same as city departments?