We haven't saved transit yet

What comes after the fiscal cliff

The transit bill that cleared the House and Senate in Springfield last week is a monumental achievement. At the 11th hour of the veto session, legislators passed a bill that saves transit in the Chicagoland region from backbreaking cuts. It also has the potential to transform our system for the long run. The bill does this in two ways.

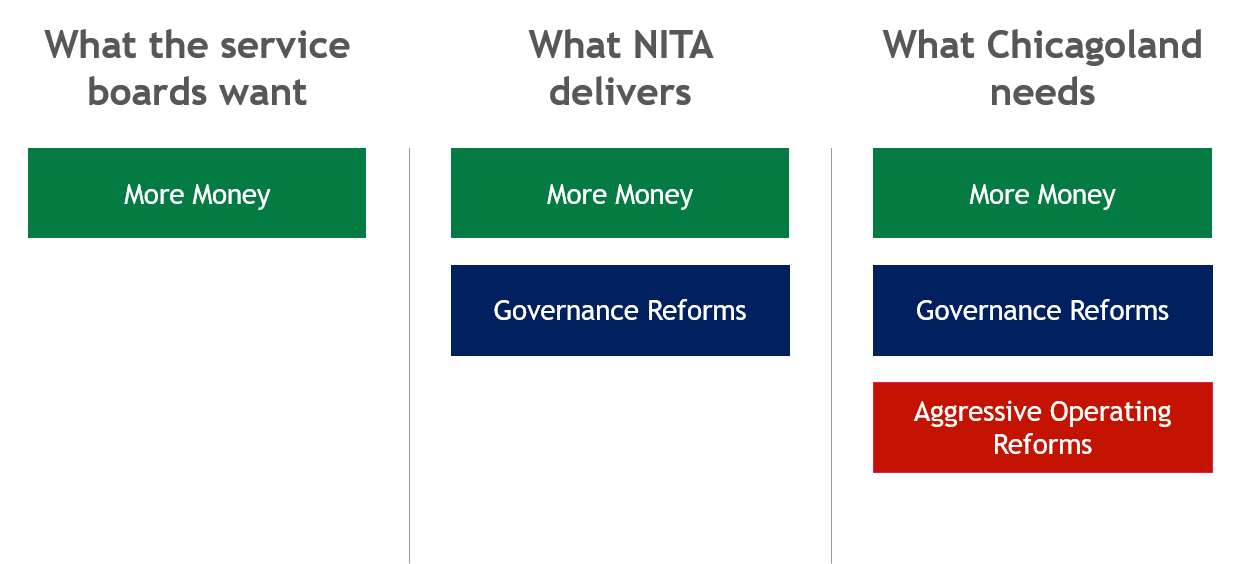

First, it implements several major reforms to the way transit is managed. We’ve covered this extensively, but the short version is that the new Northern Illinois Transit Agency will have the power to oversee a unified transit network that makes Metra, Pace and the CTA work together more effectively for the benefit of city residents and suburbanites alike. It also enables better central oversight and management of core functions like service planning, capital budgets, and safety.

Second, the bill provides $1.5B in annual funding to both address a looming fiscal cliff (estimated at $700-$800M) and to improve service. It also does so with a healthy degree of fiscal sense. The majority of the funding comes from redirecting the state’s existing motor fuel tax to transit ($860M), dedicating interest on the state’s road fund to transit ($200M) and authoring a 0.25% regional increase to the RTA’s sales tax. I don’t love that last piece, but it’s a much better approach than many of the other ideas floated.1

Getting here was hard. It required fighting through generations of city-suburb political animosity in the middle of a brutal budget environment. That success is a testament to the unprecedented coalition of labor, business, environmentalists, and transit advocates who fought to get this bill over the line. Everyone who fought for this – from the team that wrote the initial Plan of Action for Regional Transit report back in 2023 to the advocates who showed up last week to lobby legislators in a train costume – should be proud of this bill.

Source: Ben Wolfenstein

The challenge ahead

But it’s far too early to declare victory. On its own, more funding averts short-term disaster, but does nothing to solve our longer term transit issues. And while the governance reforms *could* lead to better service, there’s no guarantee of that. If we leave the same sorts of decision-makers in charge, with the same institutional memory, we could end up with little more than a cleaner organizational chart for a still-dysfunctional system.

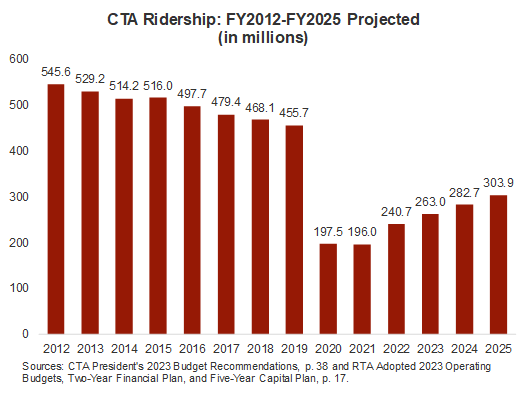

Source: Civic Federation

CTA ridership had dropped 16% in the 7 years before the pandemic hit. Key pieces of the system have been left to rot. More than 30% of the rail system is now covered by ‘slow zones’ thanks to deteriorating track conditions. And leaders of the various agencies (but especially the CTA), had displayed a shameful lack of focus on basically anything other than asking for more money. The result is a slow-moving crisis that, absent radical reforms, will continue to drag down our region – funding or not.

Better operations

These problems break into two categories. First is the operations of the system we have today. The transit agencies urgently need to deliver better service with the resources that they have. Crucially, that can’t just be measured by running more trains and buses – it needs to be measured by whether the agencies can deliver service that riders *actually want to use.* That means keeping tight control over operating costs, even with more money to spread around in the short term.

One of the better ways to measure this is by looking at the farebox recovery ratio of the system – or the share of operating costs that are covered by riders actually paying to ride the system. A higher recovery ratio indicates the system is doing a better job serving riders and controlling costs. A lower ratio indicates that the system is functioning more as a system of last resort for those with no other options, and a jobs program for employees.

Unfortunately, the RTA’s farebox recovery ratio was headed in the wrong direction pre-pandemic, and it’s cratered since. While the RTA used to be required to maintain a 50% recovery ratio (which was actually lower once accounting for a series of exemptions), the new NITA legislation drops that level to 25%.2

The common rejoinder is that the recovery ratio is a straightjacket which has prevented agencies from experimenting or cooperating with each other. But well-run transit agencies in other countries deliver far higher recovery ratios – including Berlin, a city showcased as one of the examples legislators toured as a model for NITA.3 They’ve also recovered far better than the RTA has. The pitch to taxpayers and legislators was that funding and reforms could deliver a world class transit system. Well, the money showed up. Now it’s time to deliver on that promise.

There are a lot of steps that we’ll need to take to bump that ratio up. Management will need to manage future labor contracts effectively, and ensure new service is aimed at areas with high growth potential. It will also require making operational reforms that boost ridership as a whole, even if they require stepping on a few toes. As I’ve noted before, a firmer crackdown on disorder and violence is sure to upset some on the far left, but it’s critical to rebuilding ridership.

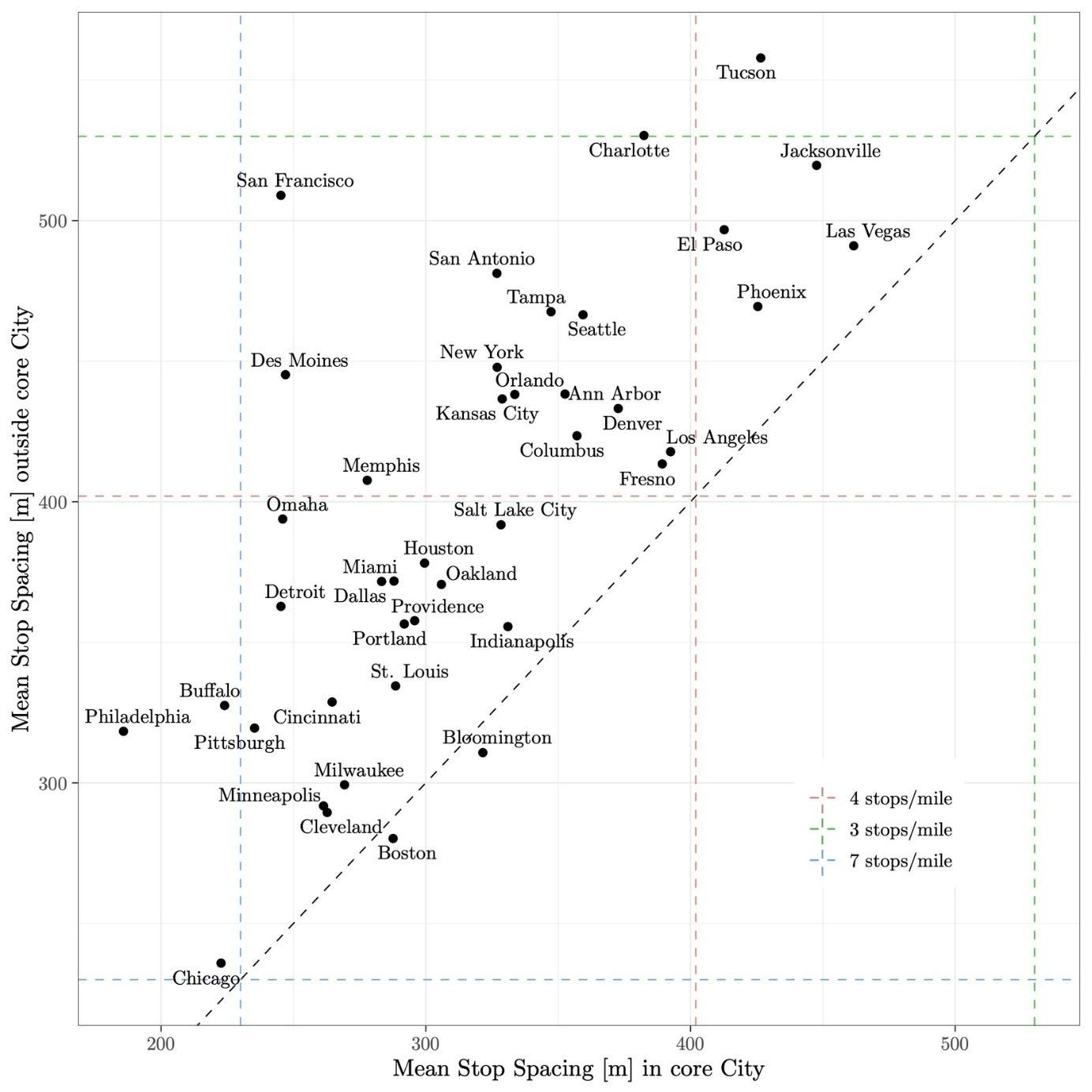

Another example is the CTA’s spacing of bus stops. Today, bus stops are comically close together – often at almost every block, in violation of transit best practices, and far more densely spaced than other US cities. Transit agencies consistently describe bus stop consolidation as the most successful action they can take to speed up bus service, which reduces costs (because it takes fewer operator hours to run a route), and improves travel times.

Source: Pandey et al, 2021

The downside, of course, is that the CTA might get yelled at by a few riders who lost the stop outside their front door. But if we want to start acting like a world-class transit agency, that’s a trade-off worth making.

Controls on capital costs

While improving day-to-day operations requires grinding out a series of efficiencies, the way we approach capital projects requires a full teardown. Here are a few examples:

Metra is about to spend $74 million to replace an existing open-air station in Hyde Park.

The CTA wants to spend $440 million dollars to replace the existing station at State and Lake with a “gateway to downtown.” Remarkably, for that price tag, we’ll somehow get no actual improvement in service beyond ADA accessibility.

Of course, the Red Line Extension, now set to cost $5.75 billion, will be the most expensive transit project per mile ever built in North America.

The cost of these projects is borne by taxpayers. They also mean that other projects never get off the drawing board. Bus rapid transit is no closer to fruition now than when Rahm proposed an Ashland BRT line back in 2013. Much worse, the CTA can’t find money to make critical repairs to the western branch of the Blue line. As the system rots, expanding slow zones mean that that branch has had the worst post-Covid recovery of any line.

For a long time, the dodge here was that the feds were picking up a large share of the cost. That excuse was never all that compelling, but it’s also much less true now than it used to be. Given the exploding costs of the Red Line Extension, roughly a quarter of the price tag is being picked up by Washington – if that money ever ends up coming at all. And the new transit bill includes $180M of annual funding exclusively dedicated to the region’s capital spending (via the road fund interest). Those are fundamentally flexible dollars coming straight out of the pockets of state and local taxpayers.

We simply cannot afford to throw that money down a rathole of unnecessary alternatives analyses and overbuilt stations. We need to drastically curtail the design ambition and revisit cost estimates for the projects listed above – and be willing to walk away if necessary, rather than put the system in greater risk. CTA and Metra also urgently need to adopt international best practices for transit cost management, bring more design work in-house, and hire transit professionals from systems in other countries that have a track record of building at reasonable cost.

This is the really hard part

It may feel harsh to focus on these challenges so quickly after a big win. But the urgency of the fiscal cliff was central to driving the hard political choices we needed to make. In many ways, the system is at its most peril now—after the fiscal cliff has been averted. With the pressure now off, it will be easy to sink back into old, bad habits. And if this opportunity is wasted, legislators in Springfield will be much less forgiving in the future.

This is the last, best chance we have to deliver the sort of transformative transit system the region deserves. We can’t afford to waste it.

Note – there are a few other really good reforms in the bill, including a statewide elimination of parking mandates near transit. Austin Busch has a great comprehensive run-down of the details over at Streetsblog Chicago.

Historically, the CTA has had the highest farebox recovery ratio of the three service boards. Density really is a crucial ingredient to effective transit.

These are just European cities. Many Asian cities have farebox recovery ratios north of 100%.

Great article. The peer cities metric is good but it is important to remember that Chicago lags far behind leaders London and Berlin with its farm-to-market rail mass transit network. You simply cannot get quickly anywhere via a train but to and from downtown here in Chicago. Evanston to OHare? Gotta go downtown first. Lincoln Park to Wicker Park? Go downtown first. In London, Paris or Berlin? There are concentric rings where you can take a subway across town with heading into the center. Chicago has had an incredible amount of legacy systems that were simply tossed out without any thought of reuse. We once had the largest cable car network in the world. It was modified for faster street cars that were junked. When walking up Kingsbury and North Ave with a development group transforming an industrial area into needed housing, we stepped over railroad tracks that are being ripped out. Why? Why not create a new light rail line to combat the traffic congestion? Our imagination needs to broaden and see what is possible. Chicago needs a circle line and ways to get around quickly during rush hour. New rail mass transit that creates new opportunities here in Chicago and improves our quality of life. Yes, have a high speed bike lane but we need less rails to trails and more new rail and new bike lanes that foster a new paradigm in getting around.

Operations planning is definitely the largest (hidden) piece of the puzzle here. I think this funding gives the agencies the cushion to hopefully do the necessary planning.

One thing that handicaps CTA bus planning in the City of Chicago is aldermanic prerogative. In a weird way, it's extremely difficult for CTA to remove or alter bus stop placement without aldermanic coordination and tacit approval. And so, CTA, perhaps due to it's existing board structure under mayoral control (to be changed under NITA) has historically avoided this fight. That needs to change.