We’re very excited to run another guest post this week. Nik Hunder is an environmental policy analyst, researcher, and public transit advocate from Chicago. And as a reminder, join us on April 10th for our first A City That Works meetup.

In early January, the Chicago Transit Authority secured $1.9B in funding from the Federal Transit Administration’s New Starts grants program funded by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL). This award is one of the largest grants in Federal Transit Administration (FTA) history.

The 5.5-mile project will bring the Red Line down to 130th Street with four new stations at 103rd, 111th, Michigan/115th, and 130th, plus a multi-story parking lot, a new rail yard, and a heavy-rail maintenance facility north of the 130th street terminal. In total, it is projected to cost $5.75B.

By all accounts, investments in the Wild Hundreds are long overdue. Mayor Richard J. Daley first proposed extending the Red Line to 130th in 1969, soon after the Dan Ryan branch opened. Today, Far South Siders experience some of the longest commutes in the region.

But while the CTA’s intent is noble, its execution has been costly and mismanaged.

First, this project is disastrously expensive. The RLE will be the most expensive transit project per mile1 and most expensive per new passenger gained2 in North American history.

Second, CTA’s cost estimates have skyrocketed since its initial grant application to the FTA. This means that FTA’s capital dollars are covering much less of this project than originally envisioned. That comes with a significant opportunity cost for other disadvantaged communities in Chicago. It also means the project is backed by a questionable financing structure that ensures CTA will be saddled with loads of debt service for the project until the 2040s3.

These questions are complicated, and it’s been challenging to piece the full construction cost story together. After multiple Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to CTA, RTA, CMAP, and the FTA and several hundred pages of records, I’m still working out the answers to key questions regarding material costs and bid details. This has not been helped by CTA’s blanket denial of numerous documents it supplied to the FTA to secure the project’s funding. The group helping me obtain these records is taking CTA to court over these improper denials, part of a troubling pattern of CTA failing to comply with FOIA.

For today, we’re going to take a deeper look at problem #2: the causes and consequences of CTA’s poor estimates.

What has caused projected costs to increase?

When the CTA first pitched this project to the FTA in 2009, the original cost estimate to the FTA was only $1.09B (not adjusted for inflation). The estimated cost remained at $1.09B until 2016, when the price doubled to $2.3B. In 2022, it shot up to $3.6B, which is partially attributed to inflation and rising construction costs (though those increases were not to the tune of $1.3B).

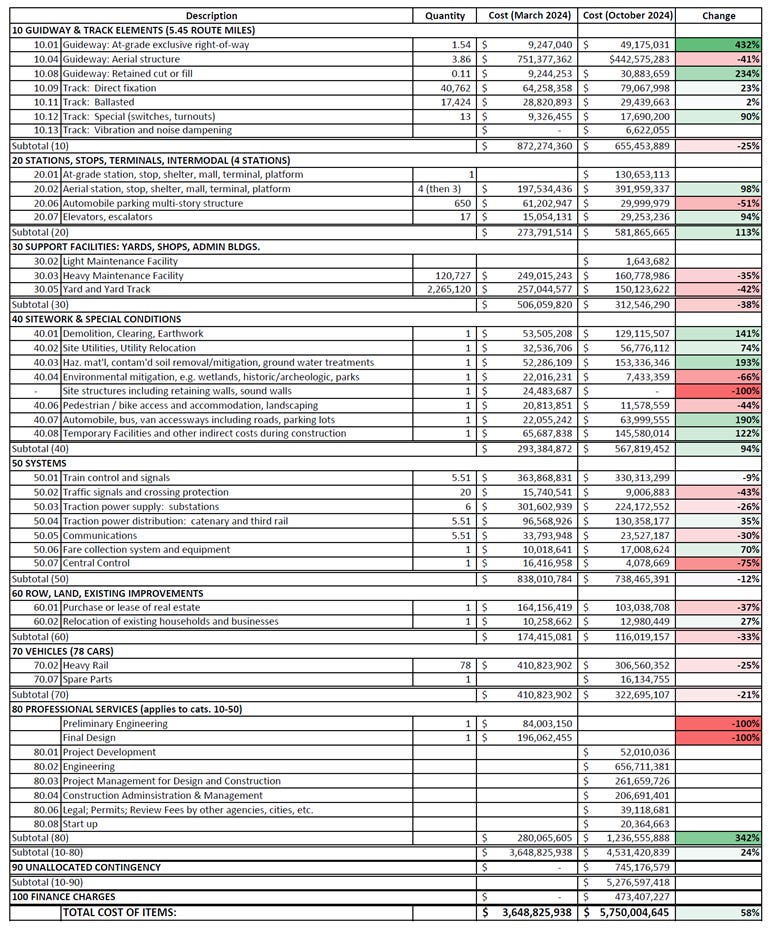

After the CTA received notice in 2023 that it was in line for $1.9B in federal funding, the cost estimates for the project continued to rise and quickly. In March 2024 it was $3.6B. In July it was $3.9B. In August, it was $4.3B, then 12 days later it was $5.3B and finally in October, it reached $5.75B. A 60% increase in seven months.

This generally went unnoticed with the exception of a few local advocates. Local media only reported the updated values as part of the overall news about the CTA’s progress in securing federal funding.

Celebrating the total value of a project is becoming a troubling trend in Chicagoland. Rather than evaluate an infrastructure project based on its value to communities, local officials are evaluating projects on how much they are willing to invest in disadvantaged communities regardless of whether it is cost effective and leaves an acceptable debt burden to those same communities and the city at large.

About Those Price Increases…

The CTA has not made it easy to understand the project’s cost structure or its cost increases. If someone were to rely on CTA press releases alone, it would appear the project cost just $3.6B in 2023 when it announced it was in line for federal funding and then $5.7B when the Full Funding Grant Agreement was signed early this year.

I was able to piece together the full story based on public filings, including the 2009 locally preferred alternative selection report, 2022 presentation to the Department of Planning, and 2020-2025 FTA New Starts Program filings with additional records from CMAP, RTA, CTA, and the FTA.

The CTA’s quarterly filings with CMAP’s Transportation Improvement Program demonstrate that it knew the entire time that the project cost was increasing. As the finish line got closer, the agency left nearly everyone in the dark.

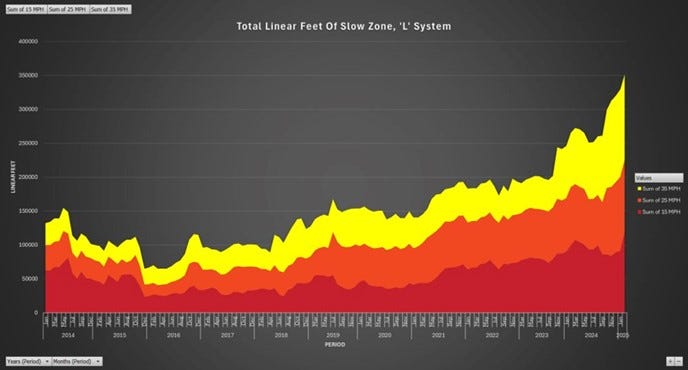

The major spike at the end of the graph is the $2B cost increase that hit the project in 2024.

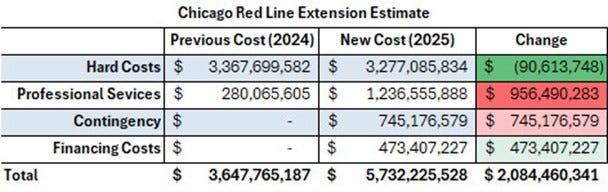

Their most egregious error appears to be in the estimates of engineering costs. CTA had only budgeted for $280M in March 2024. Seven months later, the cost was up by nearly a billion dollars to $1.23 billion. It’s so off that when looking at the line-by-line, it appears engineering costs were not even budgeted for in the CTA’s original FTA bid.

Beyond that, the agency did not factor in contingency and financing costs until the October 2024 revision of its estimated budget. But there should have been at least some financing cost for $266M in bonds it had previously announced it was borrowing, and the FTA had required $338M in contingency before March 2024. How did those numbers get missed?

Looking more closely at construction costs and professional services, after the March 2024 cost estimates were made CTA awarded a $2.9B design-build contract for the RLE in August 2024. In picking the contractor for this project, CTA issued a request for qualifications in 2023 and later that year announced it had selected three firms to submit bids.

When reached for comment, CTA Spokeswoman Tammy Chase said only two of the three firms selected(FH Paschen, Ragnar Benson, Milhouse + BOWA Joint Venture, and Walsh VINCI Community Partners) submitted bids. Spokeswoman Chase did not specify why the third contractor, Kiewit Infrastructure, selected from the request for qualifications pool did not submit a bid. With only one competitor, all the FH Paschen Joint Venture or Walsh VINCII teams needed to do was provide a better offer than the other.

Kiewit did not return a request for comment about why it did not end up submitting a bid for the project.

Between the two bids, Spokeswoman Chase said that “Walsh VINCI's contracting team bid was selected based on what provides the CTA with the best value” which was “based on a number of criteria, including the technical proposal on how the project would be built and the proposed cost,” but did not go into greater detail.

A FOIA request for the contractor’s bids was submitted to the CTA, but it refused to cooperate in reducing the scope of the final contract so that it could be released. As part of a larger pattern of lack of transparency, FOIA requesters sometimes have to sue CTA to obtain records and often face chronic delays if they ever receive a response. In this case, CTA claimed the Red Line Extension contract was too large to review and because of that, it could not be released while complying with the FOIA. A separate request for the bid from FH Paschen et al was not acknowledged.

The contract bids submitted could have been competitive. Taxpayers, the public, and CTA riders are entitled by law to know what the other contract options are without having to undertake a lawsuit that is rarely settled in less than six months and potentially requires retaining an attorney.

Messing up the professional services estimate may have been the sole error that has jeopardized the near-term future of CTA capital projects. CTA was required to submit its estimated project cost to the FTA for entry into its New Starts Program (the program where the federal funding comes from). When it submitted its estimated cost, it notified the FTA that the cost was $3.2B, and it was seeking 60% of that cost in federal support. 60% of $3.2B is ~$1.97B which is how the Full Funding Grant Agreement award amount was determined.

After it was admitted to the program, the CTA was required to notify the FTA of the increased costs, but it could not go back and continue to ask for 60% of the revised costs—it was stuck with its original estimate. Today, $1.97B is only 34% of the total cost making the local match, 66%, not 40%.

If all the budgeting failures are totaled, 85% ($1.8B of a $2.1B increase) of the cost increase is nothing but administrative oversight failures.

Spokeswoman Tammy Chase attributed the rising project costs to rising construction costs, pointing to increases in the National Highway Construction Cost Index as justification. But hard costs actually declined slightly between 2024 and 2025.

From March 2024 to October 2024, actual construction costs varied widely in the line-by-line budget (Figure 4) but overall stayed flat across eight months. That is the best one can hope for with a multi-billion-dollar project but it invalidates the CTA’s argument that inflation and construction costs were entirely to blame for the frequent price updates. The consumer price index was +1.6% during that time, which only accounts for $40M of the increase.4 The NHCCI actually has construction materials decreasing between the March 2024 and October 2024 press release announcements. Even if the hard costs remained flat, the amounts the CTA was off by are significant and do little to ensure price changes (both up and down) are not coming in the future. Hard costs remaining flat appears more of a coincidence than effective project management.

Long Term Impacts

While the total project cost continued to increase, the amount of federal funding did not. CTA based its application for $1.9B in funding when the project was expected to cost $3.2B, representing 60% of the total cost, with 40% to be paid by local funds. The local match dollars were set to come from the Red Line Extension TIF district, a Carbon Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement grant, and state funding. After all of that public support, the CTA would have only needed to provide about $266 million5 of its own money to finance the project.

When the project started to increase beyond $3.2B, CTA was not at the liberty to go back and revise its ask to the FTA—it was stuck with their original application amount. Any additional increase in the project cost had to be covered by local funds. The city council has already put in up to $959M to the project, via a TIF district running from Madison to Pershing, and the state has already chipped in $280M. There’s no indication any additional city or state funding is forthcoming. That means the CTA has to cover the increased cost.

The CTA is now planning to cover the nearly 60% cost increase (when compared to $3.6B) by issuing $2.1B in bonds at an estimated 5.5% annual rate backed by its sales tax receipts and TIF revenue. Despite the 35-year term of the bond agreement, the CTA states it plans to pay off the debt by 2043. The amount in bonds issued increased by $1.8B compared to August 2024. CTA has estimated that issuing the $2.1B in bonds will create $473M in financing costs.

This added debt puts the CTA in a dangerous position. At the October 2024 meeting of the Chicago Transit Board, CTA CFO Tom McKone reported in his financial report that CTA already had to add $407M in capital funding to the 2030 and 2031 budget to pay for the RLE. 2030/31 is a notable timeframe because it is the first outyear of the agency’s current 5-year capital plan.

The CTA needed to find the money now because when the cost of the RLE skyrocketed, the FTA revised its risk assessment, requiring an additional $407M to be provided in local funds as contingency. Having assessed another $407M for a once $3.2B project should have been the only smoke signal needed for officials to perform a more sophisticated review of the project’s finances. CTA had to propose an ordinance to its board which was passed after only one question. CTA found it was unlikely that it would need such contingency but still needs to potentially finance it through bonds in case they are needed in the the outyears. This increase is what caused the price to bump from $5.3 to $5.75 in October 2024.

Devoting this much capital funding has helped to hamstring the CTA’s capital budget. The CTA does not yet appear to have a fully fleshed-out 20-year capital plan. In the capital plan it presented to the FTA, there were unspecific plans for rail improvements other than a vague $3.2B for “rail projects.” It also lists $3.9B in funding for the 9000-series train sets CTA intends to procure in the 2030s.

A Significant Opportunity Cost

Meanwhile, Chicago still has an urgent need for other rail improvements. 77% of the Forest Park branch of the Blue Line is now under a slow zone for needed track, power, or structural improvements. Moreover, 30%6 of the entire system is under a slow zone for the same reasons. This number was only 5.5% when Carter began his decade-long tenure as head of the CTA. Forest Park branch slow zones only totaled 13% in 2015. Carter has left the agency with an expensive state-of-good-repair bill—one that has not been explicitly budgeted for in the 20-year capital plan.

The CTA estimates it needs $3B to replace all tracks on the Forest Park branch because they are at the end of their useful life. The cost increases of the RLE could have paid for a significant portion of the funding needed to repair the FP branch if the RLE funds were more tightly controlled. Other at-grade or elevated projects expecting to receive full Federal funding in FY25 are only expected to cost $423M/mi.7 CTA’s cost per mile is $1.05B. Following the national average, it could be expected that this project may have been constructed for as little as $2.4B, a little more than its pre-request for proposals estimates.

Had CTA provided a more accurate estimate to the FTA in 2020, it would have at least freed up bond capacity for the Forest Park branch rebuild.

Without a rebuild, the FP branch could fall into such disrepair it may not be safe (or at least practical) to operate on. Without proper funding secured, CTA is risking a similar fate as Baltimore when it had to suspend service immediately because all of its rolling stock had electrical issues. Rail expansions are good, but as it stands, the CTA is letting down the people it’s already promised to serve reliably with no end in sight.

The impact of slow zones has contributed to the Forest Park branch having the slowest pandemic recovery of any CTA line. Slow service has led to fewer riders, which has led to reduced service and short turns at UIC because fewer riders are on that portion of the line. It is a slow bleed that deteriorates the quality of life in an already strained area of the city. Fewer riders also mean those remaining feel less safe waiting for and taking the train, continuing a vicious cycle.

Repayment

The CTA has floated a repayment method for the RLE that could get the agency in financial trouble—or at least trigger a federal audit. In the Regional Transportation Authority’s 2025 budget, RTA wrote that:

CTA plans to issue new debt in the 2025-2029 period primarily as a match to federal funds for Red Line Extension construction. These bonds are planned to be supported by sales tax receipts and are expected to be paid back using Federal Formula Funds.

The catch is that CTA cannot pay back those bonds issued to finance its local match using Federal Formula funds. To back up, let’s pause for a grants compliance lesson. The CTA receives two major types of funding from the FTA:

FTA 5307, known as Urbanized Area Formula funds is the money CTA receives for operation and maintenance funds. This hovers around $350M/year.

FTA 5309 is FTA’s New Starts program. This is where CTA is getting its RLE money from. It requires a local match of 40% (in the case of the RLE) as part of receiving funding.

As previously discussed, the CTA needs to take out billions in bonds to pay for its local match, but it wants to repay some of the bonds of its capital project using its operating and maintenance funding. Not only is this a bad idea for providing reliable service, but it’s also not permitted by the FTA and Code of Federal Regulations for good reason.

The feds want local transit agencies to have skin in the game when they apply for capital project funding. Allowing this kind of maneuver would let grantees diminish how much local funding they are actually committing to a project. By the time the CTA starts to employ this strategy, all of the federal funds will have been dispersed and likely spent, but that doesn’t mean the FTA can’t ask for its money back or subject the CTA to an audit for non-compliance.

It’s a tricky line CTA is treading. It cannot use federal funds to pay for the RLE grant local match, but it can use them to pay for any bonds issued as a result of cost overruns or increases. Since the CTA states it will pay for its local match with bonds, it's not allowed.

To add another wrinkle, reliance on federal formula funds to repay cost overruns may be a near-term mistake. It cannot be ruled out that the current presidential administration may seek to change the appropriation levels and the actual formula FTA uses.

A President’s Role

Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson’s defense of former CTA President Dorval Carter (DRC) was often devoid of details, but he affirmed several times that Dorval Carter was great at securing federal funds. That appears to be true since the CTA ultimately got the award, but Carter left a billion-dollar mess in the process, along with significant opportunity costs and potentially negative impacts on GDP.

When it comes to an acceptable leeway of error, one would have hopes that Carter, as the highest-paid public official at the time, would have had a better grasp on the reality of the finances.

This is ultimately Dorval Carter’s failure to own up to but we’re watching in real time how Johnson and the Chicago Transit Board’s continuous rubber stamping of Carter’s actions have fared for the region.

Controlling Costs

A City That Works ran a piece last fall about the impacts of professional services on Metra’s Peterson/Ridge station—a project that ran 15 years behind and at least $10M+ over budget. The takeaways from that project certainly apply here.

Based on the timeline of the RLE prep work, it appears the CTA was slow to complete its portion of the work because it required outsourcing the most significant pieces–design, engineering, and environmental impact studies to contractors. That process requires multiple RFPs, time to review them, and months of leaving the applications open.

The CTA doesn’t need to become a one-stop workshop, but it’s clear how outsourcing most of that work can cost billions in potential federal funding. If the agency could get to a point where it could submit more accurate estimates of its construction expenses in applications for federal funding, it could save itself from many political headaches down the road and would be able to better invest in transit-dependent communities.

The Forest Park branch rebuild discussed earlier is a perfect example of such an opportunity. The full project funding is likely not coming for at least four years, so now would be the best time to put its intergovernmental agreement to work and come to the table with a complete engineering plan and cost estimate so that the ‘GO’ button can be pressed when the opportunity arrives.

As CTA begins 5 new BRT studies this month as part of its Better Streets for Buses initiative, now would be the perfect opportunity to try better in house capacity to control all costs-but most importantly, engineering costs.

If the agency gets the infusion of cash it’s seeking from the IL General Assembly, it will have the resources to take on smaller but more frequent capital projects. Having in-house labor for those projects would mean they could get done quicker; and there would be less need to supervise contractors, cutting down on wasted costs. The Transit Costs Project cited having in-house capacity as one of the reasons European countries build transit faster and cheaper than the United States.

Doing it Again

It will be a while before the CTA can secure funding for another major capital project, but it will happen. In addition to the Forest Park Rebuild, the CTA has on its plate the remainder of the All Stations Accessibility Program and the Red Purple Modernization Project - Phase II.

And we can even dream bigger. The CTA could extend the Pink Line into Berwyn, the Orange Line to Ford City, the Brown Line could connect to the Blue Line at Montrose and the Mayfair Metra station; not to mention there are miles upon miles of bus rapid transit to be built out.

With all this potential – when we do it again, will we do it like this? Or can we try something smarter?

Red Line Extension Project Financial Plan Version 7.0, October 11th, 2024

Ibid.

Ibid.

$2,084,460,341 (estimate difference) x .016 (inflation factor) = $33.4M. I added some margin with the CPI representing the whole economy. Construction has increased faster than the economy. $40M is a 1.95% inflation rate.

Mass Transit Magazine, “CTA’s RLE Project to receive $396 million increase in federal funding in project’s first year,” August 4th, 2024.

This number increased by an additional 2% between the draft and final version of this article.

Evaluated Projects included LACMTA’s West Santa Ana Branch and D Line Extension, Metro Link’s (St. Louis) Jefferson Alignment Expansion, Austin’s New Light Rail System- Phase 1 and Sound Transit’s Lynwood Link Extension. Two tunneled projects cost more per mile, BART’s Santa Clara Extension (2.1/mi) and the MTA’s Second Ave Subway Extension ($4.3B/mi). https://www.transit.dot.gov/funding/grant-programs/capital-investments/current-capital-investment-grant-cig-projects

Great article. In your research did the RTA have any useful information or analysis on the issue. They, in theory, are the regions oversight agency.

Nik, excellent analysis, thank you. Another opportunity cost lay in the lost opportunity to collaborate with Metra on connections to an improved Rock Island line, which could be upgraded to high-speed, high frequency service and get downtown a lot faster than the Red Line, which is truly a slow boat to China. Honestly, what benefit will a long, tedious, depressing Red Line ride through the middle of I-94 really provide to far south siders? Metra offers more possibilities.