How to make social housing work in Chicago: key learnings

The third and final part of our series

A City that Works recently published two pieces explaining the basics of Chicago’s new Green Social Housing Program (part 1, and part 2). Those pieces are admittedly quite dense. They also generated a bunch of additional input from folks in the know. So we thought it would be a good idea to write a final wrap up piece to update the last article’s model Pro Forma based on reader input received, and summarize some takeaways for improving the program going forward.

Importantly, this new model suggests the potential for:

Deeper affordability in GSH projects (20% of units set-aside for sub-60% AMI)

Faster rates of housing production (30-40% quicker than city estimates)

Lower market-rate rents to make developments more competitive

A linked version of the Pro Forma is available here if you’d like to follow along at home.

As previous pieces pointed out, the key ingredient to making social housing work will be lowering construction costs significantly compared to the recent costs to build affordable units in the city ($747,000 per unit in 2023). Since that condition is so critical for GSH’s success, this piece will also briefly touch on routes to achieving that goal at its conclusion.

Let’s get to it.

Key takeaways on social housing in Chicago

Social housing is a promising tool for affordable housing because it results in the city developing equity and assets, rather than continuously sending subsidies out the door. Instead of relying on year-by-year grants and government revenues that continuously cover the gap between housing operating costs and maximum affordable rents, social housing uses government resources to develop assets (a revolving loan fund, government-owned buildings) that can be continually drawn upon to support continuous affordability and that are less reliant on unstable state and federal support.

Chicago’s GSH projects will need to host market-rate units near the top of the market to support affordable units unable to even cover per unit debt service, let alone operating costs and capital expenditures. Chicago has significantly lower area median household incomes (AMI) than Montgomery County (over $40,000 lower), and significantly higher costs of construction for affordable units. Since social housing supports affordability through both lower costs of capital during the construction phase and cross-subsidization during the operating phase (e.g., profits from market-rate units are used to shore up operating costs and debt service left unmet by affordable rents), the reliance on cross-subsidization in Chicago will be more intense than in frequently cited building examples from Montgomery County (see chart below).

The current Green Social Housing ordinance imposes restrictive building and operating requirements that will make it difficult to operate effectively and for developments to pencil. The ordinance and accompanying bylaws should be amended to give the city’s nonprofit investment corporation greater discretion in putting together deals that work, while the Board provides yearly or multi-year strategic planning. As it stands, the ordinance to create GSH imposes accessibility requirements (44% of all building units must be accessible) that are four times in excess of the percent of people in Chicagoland who identify as having a disability. They also require projects to foster tenant organizations, which are not required in any other market-rate, Class A buildings. In addition to these ponderous design requirements, the ordinance stipulates that the Residential Investment Corporation (RIC) in charge of GSH must continuously consult both the Board and City Council to close out projects, tweak affordability requirements, or dispose of assets. This will impose punishing procedural hurdles for what should be standard operations in real estate development. These hurdles present a problem because they reduce GSH’s to compete nimbly against other developers, lower chances of GSH projects’ success, slow unit completions, and increase risk to RIC’s financial standing.

A GSH board controlled by the Mayor has poor precedent in Chicago and will not replicate best practices from Montgomery County. Chicago has a long history of poorly-run agency boards subject to mayoral control, including the boards for the CTA and CHA. Even if we had the best mayor on Earth, flipping a Board in charge of long-term capital planning from administration to administration is a proven recipe for disaster in housing. To ensure GSH’s board brings together the talent necessary to make GSH work - and particularly draws in Chicagoans with significant experience in top-tier market-rate developments - board requirements should be amended to reflect these needs and strictly adhered to when confirming appointments. Ideally, those appointed would also be appointed for terms that exceed Mayor-to-Mayor administrative shifts to avoid politicizing what should be a well-run operation focused on financial stability, long-term capital planning, and effective service delivery first and foremost.

A model for social housing - an updated pro forma

Readers had a number of suggestions about tweaks to our hypothetical pro forma from Part 2 in the series. In that pro forma, I took a number of assumptions based on typical costs of building operations and tried to make a social housing development pencil without additional subsidy by using the most generous terms possible under the ordinance: setting aside 30 percent of total building units to be affordable to households making 80 percent of AMI. The other goal of that pro forma involved ensuring that the GSH loan could be “revolved” - or turned back into sourdough starter capable of jumpstarting further developments - within 5-7 years’ time.

Readers returned with two core suggestions for variable inputs used for that initial pro forma, both of which are incorporated in this new model:

Readers astutely noted that while rents affordable to households making 50 percent or less AMI (what equates to about $50,000 in a two-parent, one-child household in Chicago) would make it difficult for the project to pencil, most social housing programs leverage vouchers to close that gap and to ensure that subsidies typically going out the door instead convert to government equity. As Richard wrote Wednesday of last week, housing vouchers in Chicago have a poor track record of successful uptake due to complications landlords face when deciding whether or not to accept them. Ideally, GSH’s status as a government entity would avert similar complications while also turning one-time subsidies into long-term assets. Since FMR rents - or the maximum rents HUD allows for vouchers to subsidize - are actually about the same as 80 percent AMI rents, this adjustment in and of itself does not impact the model greatly. In fact, it aids in cash flow: Since many voucher holders would likely have incomes requiring deep affordability (three-quarters of households receiving vouchers each year make 30 percent or less AMI), prioritizing those households and ensuring they move to the building with vouchers in tow would trigger the allowance for 10 percent of total building units to shift to 100 percent AMI-level affordability. The additional higher rents that the city can collect from those 100 percent AMI units reduces the need for top-tier market-rate rents to ensure adequate cross-subsidy, which, as many readers noted, would be difficult to justify given the city’s inexperience with creating competitive Class A apartments on the current market. That new rent schedule is included below.

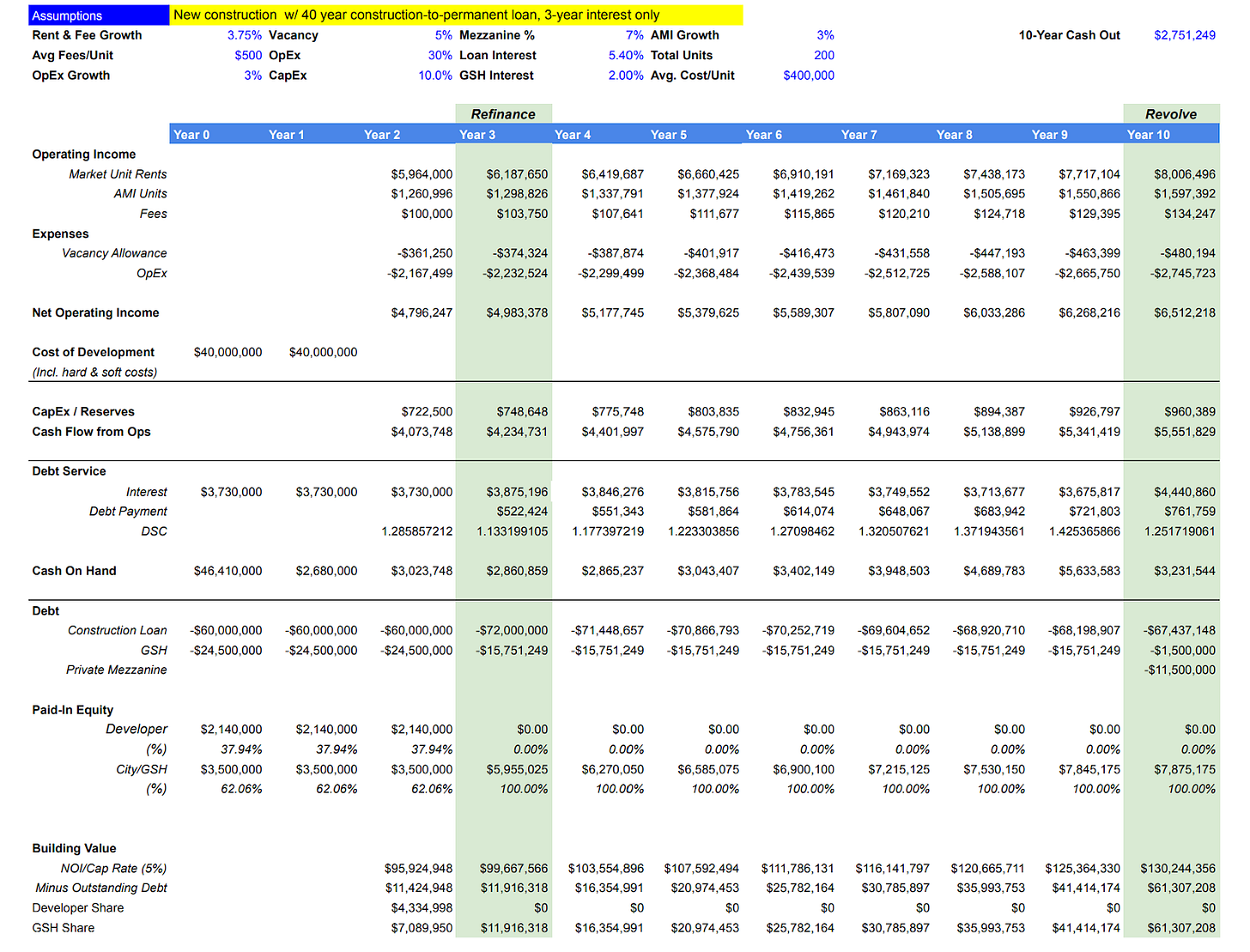

Readers noted that both FBB construction-to-perm loan flexibility and the flexibility of the city’s “revolving” loan fund could be better leveraged to simultaneously manage debt service requirements and cash flow needs. Daniel Kay Hertz, who is slated to serve on GSH’s board, reported that different social housing programs revolve loans at different rates (and at different stages) to ensure projects can pencil while maximizing affordability for units. As he also noted, social housing projects can be refinanced with higher loan-to-value ratios at stabilization, which provides a cash influx capable of quickly revolving back a significant portion of the GSH funds contributed as debt to the project. This model, which incorporates these strategies, thus breaks up the revolution of funds in two stages over 10 years, and leaves a small percentage of those funds in as equity to be cashed out at a later stage.

Other alterations had to do with model variables that would already flex according to individual projects’ management or shift according to macroeconomic conditions. First, a hard-coding error was removed from the cash flow (fully owned- by Bo, my bad). Second, in this model, the ratio of operating expenses to income has been lowered to 30 percent based on how individuals familiar with existing special property assessment programs in Cook County observed how those programs’ adjustments to property taxes have lowered other mixed-income buildings’ operating costs. Lastly, the interest rate on the FBB loan in this model has been increased to 5.4 percent to reflect the ticking-up of 10-year Treasury rates. Like the fluctuation of those rates, however, the loan’s interest could rise or fall, later, too.

So what does this adjusted model tell us? In sum, provided that the City can pull through in lowering current costs of development to $400,000 per unit, a $28 million investment from GSH could stand up a new Class A building in which 20 percent of units are set aside for voucher holders with deep affordability needs, 10 percent of units are set aside at rents affordable to households with area median incomes, and market-rate rents are competitive if not lower than similarly constructed Class A buildings. In this model, about 40 percent of GSH funds “revolve” within 3 years, while nearly 90 percent of funds revolve by the 10-year mark. Using this model, and assuming efficient redeployment of capital, the city would exceed its previously estimated rate of unit production (600 units every 5 years) by 30-40 percent on an annual basis. That’s a goal to which we should aspire.

In this new model, a small amount of money is paid back into the revolving loan fund during the three-year period before the construction loan begins its full debt service through cash interest paid on GSH debt. After that, all interest on the remaining GSH loan converts immediately to equity to ease debt service for the project.1

In Year 3, an increase in loan-to-value ratio supported by the occupation of the building provides $12 million in cash to send another $9 million back to the revolving loan fund. That’s in addition to paying out the developer’s equity share at 75 percent of “market value.”2

The result of this is that by Year 3, 40 percent of GSH revolving loan funds have been returned. By Year 10, a combination of cash and private mezzanine finance (paid back within 8 years) returns an additional 50 percent of the initial GSH funds. As with the last model, the interest rate for mezzanine finance in this equation implies that the city would rely on philanthropic or nonprofit partners to supply that debt at a below-market rate (most commercial mezzanine finance charges interest rates of 10 percent or more). That is by no means a given input, and those partnerships will be something the city should have solidified prior to finalizing any GSH deal that relies on a model similar to this one.

After this model’s full “revolution” in 10 years, the city would then have a sole building ownership stake valued at $62.8 million - given the $3.5 million left in the building as equity and total waived cash interest, that’s a 27 percent year-over-year ROI. Not bad at all!

Again, the city has to do many things right to make this model work: From ensuring below-average vacancy rates to finding reliable philanthropic partners for mezzanine finance to guaranteeing swift project completion. These will all require significant effort, but the key ingredient and arguably most difficult hurdle for a GSH model like this will be construction costs.

The key to the question - managing construction costs

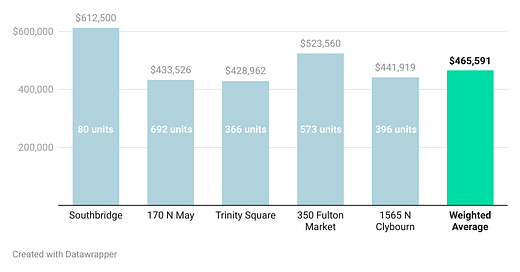

The secret sauce to making GSH work will be avoiding what makes existing affordable housing models in Chicago eye-wateringly expensive and ponderously inefficient. In the above model, the project pencils at $400,000 per unit, though affordable housing costs in the city average around $747,000 per unit. Looking toward market-rate construction as a benchmark, however, and this equation appears much more hopeful: A survey of five recent Class A apartment buildings in the construction pipeline (listed on the site Chicago YIMBY) suggests developers can build market-rate Class A multi-family buildings at just under $470,000 per unit.

Closing a $70,000 per unit gap for a project is far more manageable than a $300,000-plus gap!

There is also now a healthy and growing research base on tools to help states and cities bring down the cost of new affordable projects. In particular: researchers at RAND find that the cost of land acquisition, soft costs (like design, permitting and engineering), and project length are all major drivers of construction costs for affordable projects in other states.

That implies a few levers to help bring costs under control. Wherever possible, we should be leveraging pre-cleared sites on city-owned land to accelerate construction timelines and bring down costs. The city should move aggressively to cut permitting timelines, and avoid complex ATSM-style design requirements that raise costs and limit flexibility. Faster construction timelines (and approval of modular designs where possible, which speeds construction),3 can get buildings’ cash flowing faster, and help avert the added potential penalties of rising labor and material costs. Lastly, the city should be judicious about the amount of parking it imposes on these developments – a feature that costs a lot to deliver, but often sits unused by residents.

The point of forcing economy in per unit construction is to make projects pencil out, not to build them as cheaply as possible. We still need top-tier, Class A construction to bring in market rents required for GSH’s cross-subsidization to work. If buildings need parking or other amenities to compete for market-rate rents and to maximize building occupancy, we will need to weigh those trade-offs when deciding which levers to pull to reduce overall construction costs and to what degree we ought to pull them.

Will all this information in mind, let’s focus on the silver lining here: If we can leverage what we know about drivers of multifamily construction costs to get the City out of its own way with GSH; if we can eliminate construction costs for things not required (e.g., on-site parking) to ensure GSH residents’ flourish; and if GSH can live up to its promises and provide the mix of new market-rate housing, deeply affordable housing, and middle-market rent-restricted housing that the City so desperately needs, this will be a monumental achievement for housing in Chicago.

I believe Chicago can do it, in part because we know what making GSH successful will take. We owe it to ourselves and to everyone looking to us as an example: Let’s make sure GSH works.

Important reminder: Debt service on the bonds used to fund GSH will be paid through expiring TIF districts and do not require the generation of interest on debt that GSH loans out to pay bondholders.

That payout equates to $3.25 million, or a year-over-year 15 percent return to the partnering developer. That’s a pretty penny in addition to an assumed $4 million collected for a 5 percent development fee baked into the estimated cost of construction!

Cook County recently debuted two modular homes constructed at $100,000 a piece as part of a new slate of affordable housing initiatives from the County. True, they used donated land to build the homes, which significantly reduces costs; but in case you’re keeping track, that’s less than 1/7th the cost of building an affordable housing unit in Chicago. And it’s a whole damn house.

Amazing series! I wish I had hope the program could take these ideas seriously