As a heads up, we’ll be hosting another meetup for A City That Works readers on July 17th, at Jefferson Tap from 5:30-8:30pm. Hope to see you there!

Last week, we reviewed what social housing is, why it is generating so much interest as a new tool for addressing our affordable housing crisis, and what Chicago’s new green social housing ordinance entails. This week, we’re going to discuss what it actually will take to convert social housing in Chicago from a good concept in theory to a good concept in practice.

To briefly review, social housing provides affordable housing without the need for ongoing subsidy through two channels: First, local governments offer low-interest construction loans that increase project affordability by lowering the cost of capital. Second, governments guide those loans to fund mixed-income projects where the profits from market-rate rents can fully offset the limited ability of rents from mandated affordable units to cover debt service and operating costs.

Ensuring social housing works, then, represents a simple equation. The annual income from building rents has to be greater than the annual cost to operate the building, and pay down the financing costs (debt and equity) incurred to fund the initial construction.

Pro formas are financial statements through which developers determine whether or not developments meet this equation. Affordable housing pro formas can be intensely complex because of the capital stack required and thin margins that require highly detailed information about potential project risk and other variables.

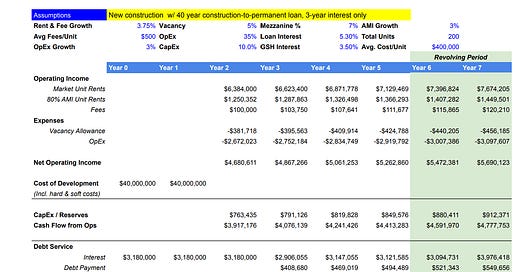

For the sake of this exercise, I am going to produce a less-detailed and more high-level pro forma based on those made available online by Local Housing Solutions and A.CRE. The point of this exercise is to determine the conditions that would make a newly constructed, affordable, and mixed-income housing development financed by GSH feasible under existing requirements.

The construction of this model will be guided by three basic premises:

If the reason we’re taking $135M off the table for closing dire budget deficits is to supplement current affordable housing dollars, I want to try and make the project work without needing to braid in additional support from tax credits or other capital subsidies. (Tax credits also cost a great deal in legal and accounting fees.) Consider it a “proof of concept” that the city could then branch from once showing initial success.

Since the city needs to maintain a majority stake in the building, and cash outflows are what can doom a project by compromising debt service, in this model I directly convert interest on GSH loan financing into equity. By ordinance, the full payoff of the initial GSH loan can only occur once the City’s equity exceeds 51% of total equity in the project. This example meets that standard.

While for the majority of this article we have discussed requirements from the city regarding building design and affordability, I also need to ensure double-digit returns for any private investment in the project in order for it to be realistically attractive. With GSH, the city is operating as an investor, not a developer. For top-notch, competitive market-rate development GSH will have to lean heavily on competent industry partners, and to ensure the buy-in of partners who the city might also expect to invest in and actually build these projects, we will have to show prowess at putting together deals that legitimately entice them to put skin in the game.

Some quick notes on terms and structure: I designed this pro forma using the most profitable parameters possible under the current ordinance, which is to set-aside 30 percent of units for households at 80 percent of area median income. At the top of the pro forma, I’ve listed all the additional assumptions I made to run the theoretical model, including loan terms, building size, and year-over-year rental increases.1 It may be helpful to outline a few terms:

Operating expenses, including taxes and property management, are lumped together and calculated in this pro forma as a percentage basis of building rental revenue rather than the sum of discrete line items.

Cash on hand is important to track throughout the analysis because of loan terms that require reserves to pay off a certain amount of debt service sans profitable operations–in this model, I try to keep reserves for about 6 months of operations and debt service.

DSC, or debt service coverage ratio, is the property’s net operating income (building income minus operating costs) divided by it’s debt service costs. That’s important to ensure risk management for the lender - most lenders want DSC above 1.20, but those supporting affordable housing can flex to 1.05 to 1.10.

Capital expenditures, or CapEx, are monies reinvested to keep up the building. We don’t want this to replicate public housing’s issue of costly repair backlogs owed to deferred maintenance.2

Lastly, you will notice GSH’s investment in the project appears in two places - both debt and equity. This is not double-counting, but meant to represent that GSH’s investment will be mezzanine debt: Unlike a standard loan, it does not require continuous payments (key for the model to work in terms of cash flow) and comes with the ability to convert debt and debt service to equity. In this model, I’ve put GSH as contributing $23 million in debt to the project with interest that immediately converts to building equity. That’s why the city appears to have an equity investment of $805,000 in Year 0 due to interest contributions.

There are a few observations to immediately note from this pro forma. First, the “revolving” period in this analysis would take slightly longer than Montgomery County’s revolving loan fund, which typically “revolves” within 5-7 years of deployment. In this model, it would take at least 7 years from loan deployment, at which point the combination of cash on hand and income generation of the project would support buying out $23,000,000 worth of GSH-issued debt through a mix of cash and privately-sourced mezzanine finance.

Second, the conditions under which this development would pencil out, even when maxing out the incomes of families living in affordable units, are very optimistic. The cost per unit of $400,000 is about half of the city’s current per unit costs of new affordable housing ($747,000). The vacancy allowance (or vacancy rate) for this project, set at 5 percent, is also lower than the area average: Moody’s reported an 8.3 percent multifamily vacancy rate for Class A buildings in Chicago in 2024, and this model is indeed premised on the city developing a truly Class A building (see the proposed rent schedule below).3 The private mezzanine financing in this model also assumes philanthropic support for social housing: Commercial mezzanine debt would more likely cost 10 percent or more on an annual basis, and would be difficult to push for the 8-10 year payback schedule required in this model.

Lastly, assuming the building would be immediately leased upon opening pushes the boundaries of belief. For the sake of simplicity I made that sunny assumption, but I doubt most developers would model building stabilization that early after construction, or that most underwriters would accept that assertion.

On a final note, the annualized return for the partnering developer who put $600,000 worth of equity into the development, assuming the city follows through on buying the developer out upon project completion (as detailed in the description of how GSH funds should be used in the Bond Book), in this model would be about 38 percent.4 That’s in addition to a $4 million development fee calculated as 5 percent of total project costs. A pretty solid return for the partner, all told!

So, keeping in mind that this model is hypothetical, what can it tell us? In sum, three things:

The city will have to take significant steps to ensure, as a partner in new GSH developments, that per unit costs are significantly reduced compared to existing affordable housing developments if GSH is to fund new housing from the ground up.

The city will have to partner with top-talent developers for new construction projects to pencil out, since they will need to be competitive with buildings at the top of Chicago's rental market in order to ensure adequate cross-subsidization.5

Even with these very optimistic scenarios, the margins that would allow this project to pencil out are thin. Given this, it seems that the more advantageous use of GSH dollars in the near future would be to inject capital into stalled private multifamily projects currently in the development pipeline, rather than building new ones from the ground up. Helping to push projects that already have debt and equity on the table but need just one more injection of funds to make it through would give the City significant leverage to demand affordability, and could extend the impact of GSH investments. But whether this is a smart long-term plan for GSH to follow (e.g., meaning we have created a development ecosystem where projects frequently stall out) is another matter for debate.

Moving toward more affordable housing for all

Optimistically, it is incredible to see the city return public housing to its roots. As GSH theoretically intends, public housing should be a shared, sustainable resource and source of pride for all of the city. But for these things to hold true officials need to carefully consider three factors when designing and implementing programs like GSH: 1) The long-term financial penalties of adding additional costs to already high and quickly rising nationwide costs of construction, 2) the truncated ability of Chicago’s local housing market to bear the weight of cross-subsidy for units set aside at affordable rates, and 3) the share and mix of affordable requirements that will allow social housing to effectively scale to the city's aspirations.6

In the City of Chicago’s Bond Book, officials predicted the GSH revolving loan fund would add 600 new units of housing to the city every five years–assumedly both affordable and market-rate. This model suggests that the rate at which GSH can add units under current constraints will be about as estimated; this represents an annual 1.5 percent increase to the total amount of new apartments added to the city on an annual basis from 2019-2023, and that is certainly something. By contrast, Montgomery County’s Housing Opportunities Commission estimates it will be building Housing Production Fund units at nearly three times the speed for the next two decades.

Looked at from another perspective, though, this hypothetical GSH project is a steal compared to subsidies sent out the door: Rather than giving away equity for affordability to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars per unit, after just issuing a $23 million loan fully repaid to the city after 7 years, Chicago ends up with a new, 200-unit mixed-income building’s majority ownership stake valued at $43 million. True, this is assets on a balance sheet - but that is a huge return for a revolving loan! (A 34 percent year-over-year return on investment if you count total waived cash interest at 3.5 percent!7)

Since GSH is a financially savvy strategy for producing affordable housing, I’m not sure the best use of funds is to prioritize the numeric share of affordable units in each individual project rather than finding a well-tuned blend of deep affordability and market rents that can quicken the rate at which loans can be revolved and thus moved into new developments, significantly upping GSH’s impact on both the city’s affordable and market-rate new housing stock. Remember, part of what makes Vienna’s social housing program work is that it hosts a variety of income types–over half of the city uses it. Conditions in Chicago are ripe for a similar level of popularity that GSH should leverage: Today, 48 percent of all Chicago area renters and 25 percent of all homeowners are housing cost burdened.

That brings me to my first recommendation: GSH needs to set clear program priorities that are not counter to one another, then invest GSH with the discretion to achieve those targets in order to make them truly competitive with market peers. Percentage-based shares of affordability per project will not necessarily support goalposts of deep affordability or boosted housing production at a significant scale. Similarly, rigid requirements for environmental friendliness, accessibility, and tenant organization (what high-end projects on the market require this?) will not set up GSH to develop projects nimbly in response to demand, putting up multiple regulatory hurdles that will not be faced by top-tier developers against whom GSH will have to compete.

Section 1A of the ordinance, for instance, allows the Board to alter the standard affordability requirements of projects “if the Board deems it necessary for the financial sustainability of the Development in order to meet program priorities,” including lowering the percentage of overall affordable units required to support deep affordability in a project (e.g., housing affordable to families who make 30 percent or less of AMI), or flexing max AMI requirements for projects to up to 100 percent of AMI to make new developments pencil out.

The Residential Investment Corporation that will administer GSH should immediately have this discretion, rather than needing to go to the Board for approval, in order to swiftly push through deals that are clearly viable, potentially capable of supporting deep affordability, and, ideally, that also shorten timelines of loan revolutions.8 On a yearly or multi-year basis, the Board could then revisit how market conditions will enable different program priorities. After that, it can work with the Corporation to hammer out new priorities to emphasize in deals as needed.

On a related note, I think it’s also concerning that high-level asset management related decisions for GSH (e.g., disposing of underperforming property unable to bring in rents required to sustain operations9) require approval of BOTH the entire Board and City Council. By contrast, the Chicago Housing Authority merely needs a simple Board majority and approval from HUD to dispose of holdings it no longer can sustain or does not require. Why would we make it hard for ourselves to dispose of assets that could potentially cost the city millions if not tens of millions of dollars if they began to fail?

A discretionary approval process and lack of clear goals for directing development will slow GSH down and impose a layer of unnecessary review upon it contrary to the spirit of the Mayor’s ongoing Cut the Tape initiative. As Richard wrote in the Sun-Times: “We can build high-quality affordable housing at scale, or we can build specialized projects that gesture at a laundry list of other laudable policy goals. Pick one.” Delays and discretionary approvals cost time and money, and these are not something affordable projects can themselves afford.

My second recommendation is related to the first: The City and the Department of Housing need to align resources and design guidelines to significantly lower costs of affordable housing production and to ensure GSH units can pencil out with mandated affordability. What might this mean? Well, for starters:

A menu of off-the-shelf, by-right design options for GSH projects that can ensure target affordability by lowering construction costs. These could include removal of mandatory parking minimums, streamlined approval of projects in planned development zones, and, when available, unconditional approval of the use of modular construction.10 (The Resurrection Project has already done amazing work using this innovative tool.)

Pre-clearing city-owned sites in or immediately adjacent to high-demand, strong rental market areas for GSH development, to remove the significant costs and delays of site acquisition and review. And while we’re at it, GSH should make sure it builds large buildings on sites to take advantage of free land via economies of scale: Montgomery County Housing Production Fund projects typically have 200-400 units, while the average Chicago Department of Housing multifamily building has 50 of them.11

Collaboration with the Cook County Assessor’s office and the State of Illinois to determine the full suite of property tax exemptions for which GSH projects could qualify, then set guidelines for how projects can effectively secure them.12

My last recommendation has to do with the organizational structure of the Residential Investment Corporation that will implement GSH, because neither of my first two recommendations will hold water without a Board that knows how to compete with top-tier developers and create long-term assets that are self-sustaining. GSH needs to build out a Board highly competent in market-rate development and long-term asset management, with expertise on par with top-tier real estate developers. The current ordinance and bylaws for GSH do not clearly provide for this crucial enabling feature.

The Board structure outlined in the final ordinance will consist of six ex-oficio members from existing City government bodies (including DOH and DPD), two resident members, and seven members to be appointed at the discretion of the Mayor provided they have expertise in market-rate development, “affordable housing development or asset management,” housing or sustainability organizing, or labor relations. So, at best, 3-4 of the 13 members of the Board might have the requisite expertise to make GSH units competitive with the existing market. (We also do not have a great track record with Mayoral-appointed Boards for agencies that require deep expertise, like in transit.)

For comparison, here’s the Montgomery County Housing Opportunity Commission’s Board of Commissioners:

Roy Priest, former head of the Alexandria Redevelopment Housing Authority, Director of Economic Development for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and CEO of the National Congress for Community Economic Development.

Robin Salomon, affordable housing developer that has built over 7,000 units in multiple states.

Jeff Merkowitz, senior advisor to the CDFI Fund created by the U.S. Department of Treasury to facilitate community economic development, and former CFO for the Opportunity Fund, itself a Community Development Financial Institution.

Linda Croom, educational paraprofessional and former long-time president of the HOC Residential Advisory Board who has now served as a commissioner for nearly a decade.

Jonathan Miller, former Deputy Director of Policy and Research at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and 23-year Congressional staffer who worked on the Senate Committee for Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs.

Izola Shaw, current council member in the City of Rockville who serves as a liaison to the Rockville Human Rights Commission, Rockville Housing Enterprises, and Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments’ Region Forward Coalition.

Paul Weech, former president and CEO of NeighborWorks America, senior leader at the Housing Partnership Network, 10-year Fannie Mae employee, and chief of staff at the Small Business Administration.

By all counts, let me be clear - this is a knock-out board for an affordable housing agency that would be difficult to replicate anywhere outside of the Washington, D.C. metro area. But there are lessons in it for Chicago to follow: Build a board that will enable you to meet program goals of building competitive developments that can sustain valuable assets with permanent affordability, not meet the needs of administration-by-administration political whims.

The Mayor’s proposed appointments from June 18 fall somewhat short of this critical component to replicate Montgomery County’s recipe for success. Of the seven proposed members Mayor Johnson presented to City Council as of Wednesday, one has experience in large-scale affordable housing finance (Daniel Kay Hertz), one has a background in sustainable construction (Juanita Garcia), one has a background working for Goldman Sachs managing a large-scale real estate investment trust (Gwendolyn Hatten Butler), and one has experience with significant public housing and community revitalization projects (William W. Towns).13 The others are talented professionals with a potpourri of experience in the wider orbit of community development and affordable housing. But they have little direct experience with building and financing the types of competitive, large-scale market rate developments at a Class A-level that Chicago will need to make GSH pencil out.

We have actually created an affordable housing board that operated according to the whims of Mayoral politics in the past, and its history should have been infamous enough to teach us that boards composed in such fashion are bad ideas. Yes, I’m talking about the Chicago Housing Authority, whose shift to firm Mayoral control under Richard J. Daley gave us characters like “Flophouse Charlie” Swibel (forced to resign under pressure by HUD). These problems have not gone away, either. As mentioned earlier in this article, CHA properties face an ongoing maintenance backlog that has routinely led to low scores on HUD inspections. In 2016, the Better Government Association determined that the agency was boosting executive pay beyond caps while sitting on hundreds of millions of dollars of unused funds for development. Woof.

The lesson is that since affordable housing projects operate on razor thin margins, bad decisions can quickly snowball into crises. It’s important to create a board and board governance structure for GSH that ensures we do all we can to make GSH projects work for the long-term, operate with minimal risk, and avoid these dangerous situations.

To close things out here, I want to make sure to emphasize that the creation of GSH remains an incredibly significant achievement, one of the many reasons I am proud to be a resident of Chicago. To ensure that GSH fulfills its promise as a ground-breaking initiative to increase housing availability and affordability for all Chicagoans for the long-term, we need to ensure it operates with full awareness of the financial complexity and whipsaw volatility of housing markets, not according to short-term whims and political pressure.

To start an affordable housing program by binding it up in requirements that shrink the scope of likely success is to recommit the same sin that housing expert Catherine Bauer bemoaned of U.S. public housing–the program she helped make into a reality–in a 1957 retrospective. As she wrote in “The Dreary Deadlock of Public Housing,” she considered the program a dwindling promise frustrated by political engineering that left it “not dead but never more than half alive.”

What might make us feel good for the short-term can in the long-term leave affordable housing projects unworkable, program goals unfulfilled, and city agencies insolvent. That has been the lesson of public housing programs that have tried and then foundered in attempting to solve too many disparate problems at once (income inequality, neighborhood inequality, housing shortages, and the racial wealth gap, to name a few). That has in fact been the lesson of many well-intended housing programs in the U.S. going back to tenement reforms, whose frustrated ends I have spent nearly a decade studying for my dissertation and a forthcoming book.

This is a major chance to turn a new page for a long streak of frustrated dreams for U.S. housing, and particularly the frustrated dreams of equal and affordable housing in Chicago. Remember: The nation is watching to see if Chicago can join Montgomery County and prove that social housing can live up to its promises. Similar programs are being considered in Seattle, Chattanooga, and California.

We should be the City That Works. Let’s make GSH work like it can and ought to.

This can be waived if the project can somehow guarantee continuous affordability and gets approval from both DOH and City Council

The construction loan is assumed to be reflective of one available under the Federal Financing Bank’s risk-sharing program, which adds +1 percent to outstanding 10-year Treasury rates.

OpEx for this project are set on the low range for a property, at 35 percent. CapEx/Reserves represent the annualized cost of capital maintenance and repairs for a project, the unused portion of which would be set aside for reserves to be used for large repairs. The 10% percent figure for that expense and set-aside is based on the high point of guidelines for CapEx by income, since we want public investments to be well-maintained. See for instance, RCN Capital (2023), A.CRE (accessed 2025), and Stessa (accessed 2025).

While the rent schedules for affordable housing in the model are taken from DOH’s website (AMI), I based the market rate rents (pictured below alongside affordable rental rates) on Class A buildings like West Loop’s Parq Fulton and The Foundry located off North Clybourn, but built in a slight discount in order to make these units more competitive.

I assume a 25% discount on the value of the developer’s stake at the point of sale. The rate of that discounted purchase would likely be hammered out in the initial development deal.

To clarify what I mean by this last point, since the loss on market rate rents for affordability at even 100 percent AMI compared to Class A market rents is more significant for some unit types than the loss of revenue between 40 percent AMI rents and 80 percent AMI rents, there is a policy debate to be had about whether mandating smaller overall percentage of units with deeper affordability (e.g., 30-50 percent AMI) would be a more valuable contribution for the social housing program than setting aside 30 percent of units at 60-80 percent AMI. Some would argue we’re already doing this through our ARO program, which focuses on providing units at 40-60 percent AMI affordability, but the paltry rate at which we’re building ARO units (between 100-150 per year) suggests the finances of that program without subsidy or discounted costs of capital are not terribly enticing.

An important note here: Debt service on the bonds used to fund the revolving loan fund are supposed to be covered by expiring TIF districts, which means that GSH should have the flexibility to turn interest into equity rather than needing it for debt service.

Degree of affordability versus expediency in development speed and minimization of social housing project risk is a major subject of debate. See this recent story published by Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies to learn more.

In theory, the Residential Investment Corporation could sell an underperforming asset unable to meet operating expenses to a buyer on different conditions of affordability or, if the city really needed the asset off its books, to convert the building to market rents.

Modular construction’s benefit is not directly lowered costs of construction (modular buildings can cost about the same in construction costs) but rather the level of speed and customization it offers, which both reduce soft costs of development and increased projects’ ability to meet resident needs.

This number comes from the Chicago Data Portal, and is the average of only Chicago Department of Housing multifamily developments.

I also wonder if the Corporation that will implement GSH could partner with Cook County to develop on sites in the Chicago suburbs where the rental market was recently declared the most competitive in all the country, building off the prior success of the Gautreax voucher program in opening up additional areas of opportunity for those in need of affordable housing. RIP to Alexander Polikoff, the lawyer who spearheaded the Gautreaux case behind the program, who died last week.

This is great. I worry the challenge is even steeper than you suggest, though. Specifically, the cross-subsidy part. Those market rents you assume to make this deal pencil are crazy. There is no way GSH will produce market-rate units that successfully command $5,700 for a 3BR, $4,600 for a 2BR, and so on. It's hard to believe that anyone in Chicago can charge those rents (even private luxury developments). (Someone who can afford $4,600 rent could afford to buy a home in the $800-$900k range even with today's high interest rates.) It's even harder to believe that GSH developments could compete with those private developments. And even if GSH can produce incredibly high-quality high-rent units, people are going to find it hard to stomach a city enterprise focused on affordable housing charging such high rents. And on top of all that, if GSH (and other reforms like cut the tape) succeed at boosting supply of new units, that will have the most direct effect on the new/high-end of the market; it will make it harder for GSH and private competition to charge rents so high.

We're in desperate need of more affordable housing, so I'm very supportive of this. One of the many challenges CHA has with its mixed-income developments (1/3 of housing at or below 30% of AMI, 1/3 at 40% -80 % of AMI, and 1/3 at market-rate) is its difficulty finding market-rate renters. That same challenge will need to be addressed for GSH.

When I was a Franciscan friar many lifetimes ago, one of my favorite philosophers in theology was John Stuart Mill, who once said, "He who only knows his side of the case knows very little of that." This board would benefit from members who have a greater understanding of "the other side of the case."