How has the city budget changed since 2020?

To find savings, let's first look at where we're spending more.

It’s been about a month since my initial post on this year’s budget, and my prediction that the proposal was far from final seems to have held up well. We’re still yet to pass a budget, though on Tuesday the Mayor’s latest proposal narrowly advanced out of committee.

Unfortunately, however, the latest proposal remains thin on savings. While the proposal’s property tax hike is down to $68.5 million - and tied to the increase in the cost of living from the past two years, which I’ve advocated for previously - it instead primarily replaces that revenue with a slew of around $165 million in other fee and tax hikes to close our budget gap, instead of focusing on addressing the spending side.1

Last week, 28 aldermen sent a letter to the Mayor outlining their priorities and requests for the budget as we near the end of the year, including a list of spending cuts the Mayor’s team was proposing. They also recommended some measures including a reduction in the Mayor’s Office staff back to 2020 levels, as well as eliminating some redundant roles. These are good suggestions. Separately, a couple weeks back, 15 alderman floated a proposal to right-size the entire budget back to 2020 spending levels, generating over $500 million in savings. That strikes me as very hard to actually do - as we’ve covered, salary costs are subject to CBAs; we can’t just roll them back entirely - but it’s an interesting idea and I think it’s directionally correct.

Unfortunately, I haven’t actually seen much more about exactly how our spending’s changed since 2020, or what a return to those levels could look like - so that’s what we’ll get into today.

Where has spending increased the most since 2020?

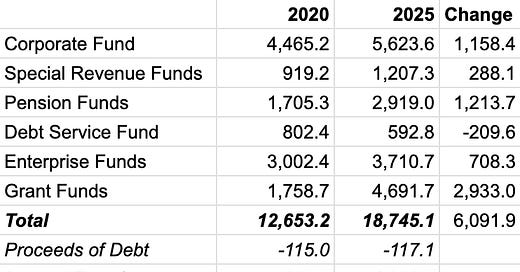

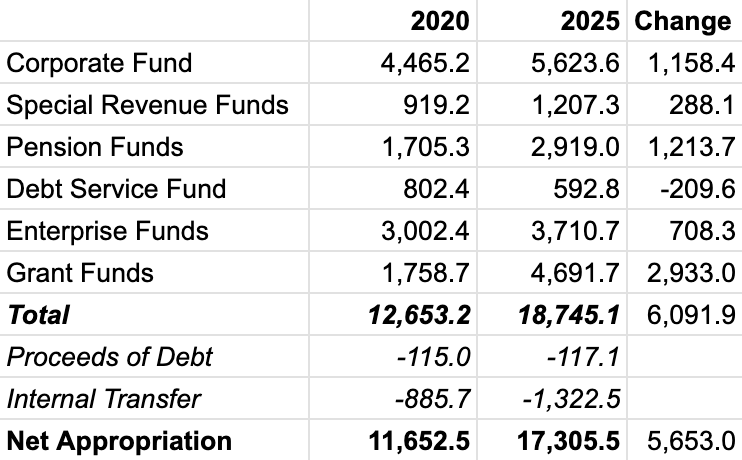

Starting at a high level, here’s spending across the various budget funds in 2020 and 2025:

Inclusive of grant funds, we’re up to $17.3 billion in spending this year, or over $5.6 billion higher than in 2020. Nearly $3 billion of that increase is specifically Grant Funds. We’ve also had a big increase of $1.2 billion in our pension fund spending - this makes sense, given that we’ve climbed the pension ramp - and over $700 million in our Enterprise Funds (these are somewhat irrelevant to the overall budget, since they’re self-sustaining enterprises). We can basically set all of those aside. But the Corporate Fund - the main part which we do control - is up about $1.15 billion, or roughly 26%. Where’s that money going?

Based on the budget recommendation books2 for both years, we can break this down by spending purpose. While the Corporate Fund as a whole is up about 26% since 2020, that varies widely by function and department.Spending on the Department of Housing, for example, is actually down nearly 30% - while the Department of Planning and Development is up over 40%. For a full list, in lieu of dropping in a bunch of duplicative tables I’ll refer you instead to my Google Sheet here for a full itemized list: Corporate Fund Spending, 2020 vs 2025.

To narrow in on the biggest things, here are the eight specific lines with a budget increase3 from 2020 to 2025 of at least $10 million and 30% (e.g. things where we’re spending a lot more in both relative and absolute terms):

Spikes aren’t necessarily proof of an issue - OPSA, for example, was a brand new entity in 2020, so we’re starting from a pretty low level in 20204 - but they’re a good starting point on where we should begin looking into deeper structural reforms to fix spending. I’m very happy with my garbage collection service - but their budget is up almost 50% since 2020. What are we getting for that extra spending?

Similarly, the Department of Family and Support Services does important work, but as of 2025 the vast majority of their $955 million budget comes from non-Corporate Fund sources (mostly $743 million in Grant Funds). Are we spending that grant money as efficiently as we can be, and are we sure that we have no room to shift any of our current Corporate Fund spending into those grants? I am skeptical.

How much could we actually save with 2020 staffing levels?

As another exercise, I wanted to look at what we could actually save if we rolled back employee counts to where they were in 2020. This isn’t quite as simple as “restore funding to 2020 levels” - salary cost per employee has gone up since then, based on our agreements with the various unions - so I followed this simplistic approach:

Get Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) employee headcount in the 2020 and 2025 budget for every department

Get total personnel spending in the 2025 budget proposal to estimate cost per FTE

If 2025 FTEs are lower than 2020 FTEs, leave them alone

If 2025 FTEs are higher than 2020 FTEs, roll back to the 2020 figure

Use those 2025 cost-per-FTE figures to figure out how much we save per eliminated FTE

As an example, the 2025 budget proposal shows 123 FTEs in the Mayor’s Office, with a total personnel cost of $14,366,265 ($116,799 per FTE). The 2020 budget only funded 116 - so rolling back those incremental 7 FTEs generates around $817,600 in cost savings.

I repeated this exercise with every other function/department on the city budget, based on the 2025 and 2020 budget outlooks, and then made a few choices5:

I’m assuming any FTE changes for O’Hare, Midway or the Department of Water Management can’t add any value to us - those all come out of the Enterprise Funds - so I ignore those.

I’m assuming we don’t want to change anything within Public Safety, because it’s public safety.

With all of that done, I end up with around $124 million in reduced personnel expense if we restore 2020 staffing levels for everything else where we’ve increased FTEs:

There are a fair number of departments where our headcount is up significantly and we could see real savings by going back to 2020 staffing levels:

The City’s Department of Human Resources - which we’ve already covered doesn’t seem to be too focused on hiring well - is up 50% in FTE headcount, and eliminating those incremental 41 FTEs could save $4.2 million or so.

Streets and Sanitation’s Forestry and Street Operations divisions are up by a combined 79 FTEs - that’s about $8 million. I’m cognizant that those are important services, but I don’t recall 2019/2020 as having issues around those services being inadequate - and it’s worth noting that other portions of S+S, like Sanitation and Traffic Services, are all largely flat. Beyond that, Streets and San is reporting that tree trimming services got more than twice as efficient in the last two years. That’s a real credit to the department! It also means we shouldn’t need to add an additional 79 positions at the same time.

Staffing in the Department of Public Health has nearly doubled, adding over 400 FTEs - almost $56 million in personnel cost - since 2020. The majority of their budget comes from Grant Funds, but it’s worth looking into how fungible those dollars are and whether any of the Corporate Funding still going to DPH can be reduced.

That last point is an important caveat - because not all of these positions are funded from the Corporate Fund, that $124 million figure is almost certainly too high. CBA rules also make it more likely that our cost savings per layoff will end up lower than the per-FTE figures I calculated here.6

Given that, let’s assume there are a bunch of issues around revenue-fungibility making many of these staffing reductions not doable. There are also probably other instances where we don’t want to fully roll things back - I’m hesitant to make cuts to Housing or Planning + Development headcount in case they’d slow down construction projects, for example - so let’s just cut the overall savings figure in half. That still gives us over $60 million - nearly equivalent to the $68.5 million property tax hike the latest budget proposal includes.

The Mayor has placed a big emphasis on not wanting to impact city services by instituting spending cuts, but it’s hard for me to imagine that we’d see a major collapse in city services if a few departments returned to the same headcount they had in 2020. I see about $14 million in savings, for example, by returning all Finance and Administration spending (departments like Human Resources, Finance, the City Clerk and Treasurer’s offices, etc.) back to their 2020 staffing levels, and I’m pretty skeptical that would have any noticeable impact to the public.

The Bottom Line

This latest budget proposal, much like the first, still avoids making the hard choices around spending efficiencies which we’re going to need to make as a city. If we don’t make changes this year, we’ll have an even harder time next year, and the year after that, and the next after that.

With both the revenue and spending plans clearing committee on Tuesday, my understanding is that City Council will likely vote on both as soon as Friday. It’s not clear whether there are sufficient votes to pass the budget, and I think it will be close. If you live in Chicago, I encourage you to reach out to your alderman7 encouraging them to vote against this budget and push for the city to get serious about structural reforms to our spending.

The largest spending change I’ve seen described is a $74 million elimination of the basic income pilot program the city’s been running the past few years (the Sun-Times mentions this here). While I’m definitely in favor of that cut (it’s the sort of ‘nice to have’ experiment we just literally can’t afford right now), I think there’s a big difference between sunsetting COVID-era pilot programs and making hard decisions about structural spending - and I don’t see anything on the latter.

One footnote here: the city’s IT department has bounced around over the years. To be precise, I am comparing the Bureau of Information Technology (within the Department of Asset and Information Management) in 2020 to the Department of Technology and Innovation in 2025.

That said, there’s probably a separate question on whether OPSA is worth keeping around at all - see this BGA report from 2022 on some evidence that it’s not saving us money.

If you want to follow along, or find where I might’ve made an error, my Google sheet with the data I’m using is here: 2020 vs 2025 FTE Cost

As a general rule - and in all the city collective bargaining agreements I looked at - CBAs will require a ‘last in, first out’ policy where the least-tenured employee at a position has to be laid off first. Given the tenure-based pay structures for most city union jobs, those employees likely earn less than the average employee at that position.

That link should do the work for you, but just in case - in the same vein as our usual election guide promise: if you don’t know who your Alderman is, please reach out and I will be happy to point you in the right direction.

Thank for sharing this! I personally find budget talks super difficult to follow, and you made this very neat and concise.

Also, thanks for holding the line about structural spending changes instead of one off patches. You did a great job of being diplomatic in your assessment, but I think you have latitude to be more directly critical about our spending choices. A 50% jump in HR spending with no discernable reduction in hiring timelines is bananas.

Thanks for writing!

This is a fantastic resource - wish it had been out earlier!