What Does Better Growth look like?

Lessons from Austin, Texas

Living in Chicago has given me the chance to work with urbanists, YIMBYs and abundance-minded peers. But I've also met plenty of Chicagoans worried that rapid growth will wipe out the character of their neighborhood. What I find both of these camps have in common is that their concerns are mostly hypothetical, since the people making them haven’t actually lived through the type of neighborhood growth they envy or fear. But I have, and I would like to share some of that experience to contextualize these arguments.

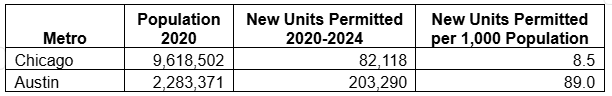

I lived in Austin, Texas from 2011 to 2023: for much of that time, it was the fastest-growing large city in America. Austin built the housing to accommodate this growth, too: every year since 2010, the Austin Metropolitan Area has built more new housing than the Chicago Metropolitan Area, despite having less than 1/4 the population. In recent years this has been downright humiliating: from 2020-2024 the Chicago Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) permitted about 80,000 new units of housing. The Austin MSA permitted over 200,000. The Austin region has built new housing per capita at a rate over 10 times that of Chicagoland.1 This hasn’t just been a bonanza of “luxury” developments for the affluent, either: Austin has built more affordable housing than any other city in America as well.

Or to put it another way:

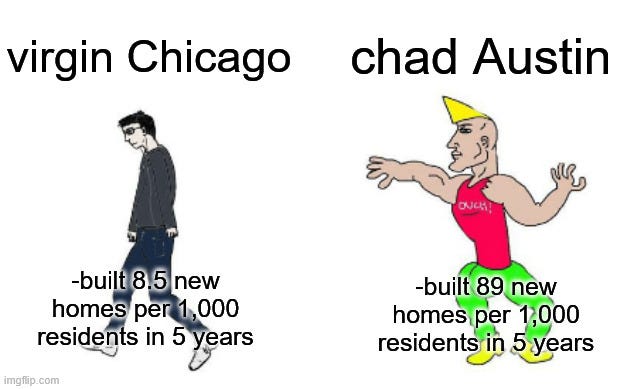

This growth has brought immense benefits to the region, which has grown larger and has become significantly wealthier. And the unabated home construction has led to higher vacancy and decreasing rents over the past 3 years.

But there are better and worse ways to grow. The two neighborhoods I lived in serve as perfect case studies.

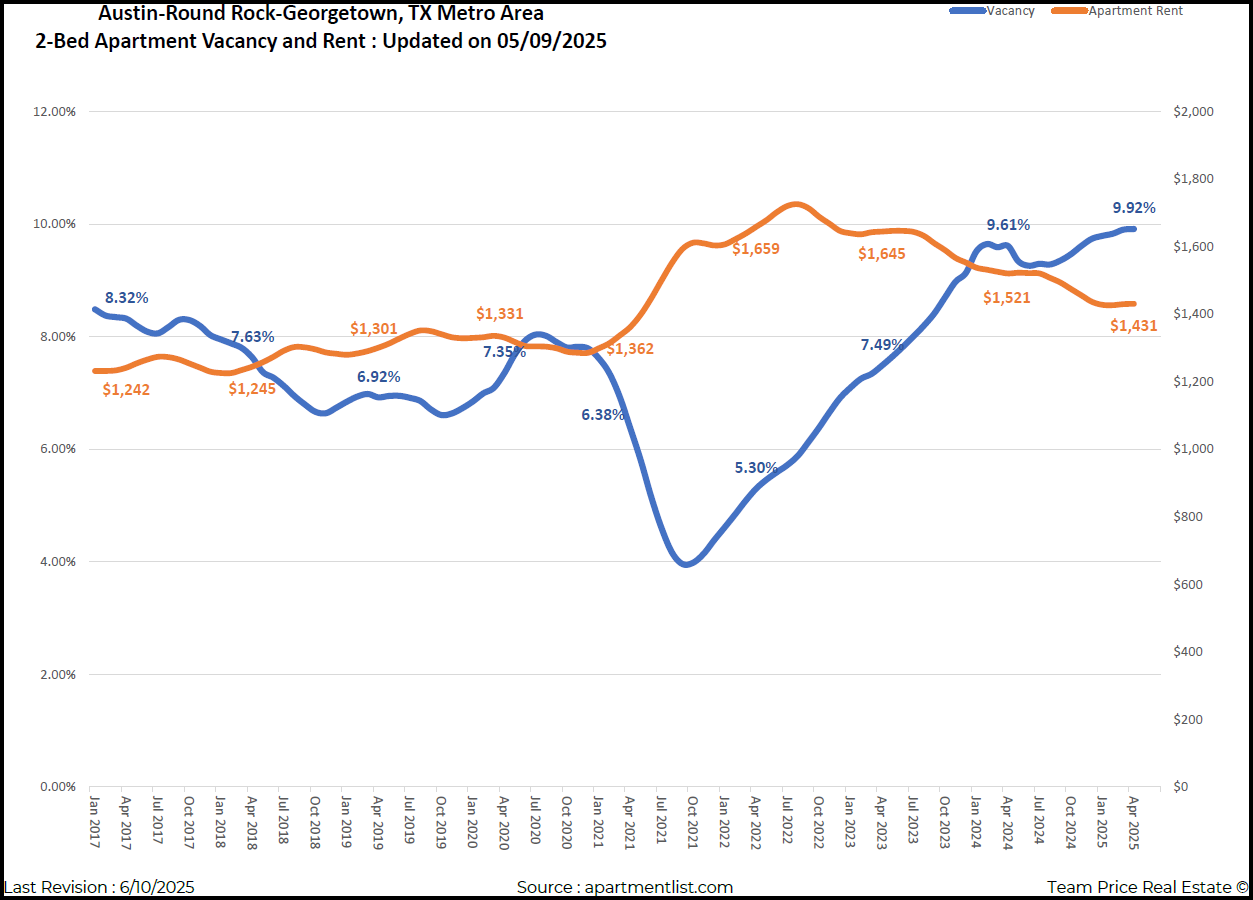

Displacement in East Riverside

Let’s start with the bad: in 2011 my partner and I rented a condo at 1201 Tinnin Ford Road, just southeast of downtown. South Austin had historically been working class, and our neighborhood of East Riverside featured a vibrant Hispanic community, a local supermarket, cheap apartment complexes, and empty lots where other cheap apartments had been recently torn down.

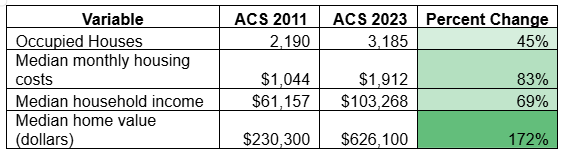

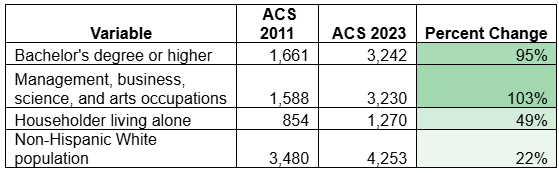

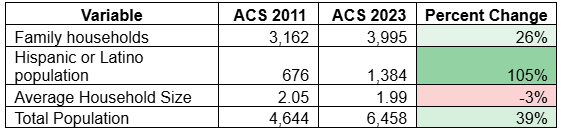

Census tract 23.04 of Travis County, East Riverside neighborhood

East Riverside was slated for a major redevelopment due to its aging multifamily housing stock and close proximity to downtown. The redevelopment efforts originated from a 2006 neighborhood plan of the surrounding region that explicitly identified as its goals “preserving the single-family homes and the character and assets of our traditional neighborhoods” (pp.26-27) along with protecting the local shoreline, creeks, and golf course. No mentions were made of protecting renters.

As a consequence, all growth in the area was pushed into places already zoned for multifamily (East Riverside). To make matters worse, the existing multi-family housing stock had all been built around the same time and was starting to deteriorate. After decades of minimal new construction, East Riverside was now faced with a deteriorating housing supply and massive demand for new housing.

The results were predictable. As the existing multifamily stock was replaced with new, high-end apartments rents spiked and existing residents had nowhere to turn. Our rent went up by 50%, and with no existing units remaining that we could afford, we had to move elsewhere. As it turned out, that was just the beginning - Oracle would later build its new Austin headquarters in East Riverside, further accelerating the area’s rapid gentrification.

New apartments on empty lots, before and after

Increased density replacing existing apartments, before and after

Oracle’s new headquarters, before and after

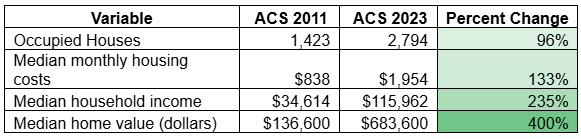

From 2011 to 2023, the number of occupied housing units in East Riverside doubled. Median housing costs also doubled, median household income tripled, and the median home value increased five-fold. Even after controlling for inflation (35% from mid-2011 to mid-2023) these increases were enormous.

Most of the people living in East Riverside in 2011 did not benefit from this massive influx of wealth. Alongside the economic transformation came a textbook case of displacement. The number of Hispanic residents and family households fell by two-thirds, while the number of non-Hispanic White residents and non-family households quadrupled. The number of residents with bachelor’s degrees or higher and the number working in “management, business, science, and arts occupations” both increased more than five-fold.

But what’s so stunning about the “growth” of East Riverside is that during this same time period the overall population actually declined! How is this possible, when the number of occupied housing units in this same area doubled? Because the average household size over that time tumbled from 3 to 1.3 people.

To be clear, these results would not have been better if East Riverside had replaced those aging apartments with single family homes instead. The household count would have grown less, but long-time residents would still be displaced. The neighborhood would have just ended up with a smaller number of residents in even more expensive homes – and the rest of Austin would’ve felt even more displacement pressure without new apartments to soak up demand.

But this story is still something that many Chicagoans fear, and rightfully so. Hundreds of millions of dollars of investment were poured into the neighborhood, with no benefit to existing residents. Hispanic families were priced out and displaced by upper-middle class white professionals,2 all to ultimately house fewer people at the end of the day.

Good Growth in Crestview

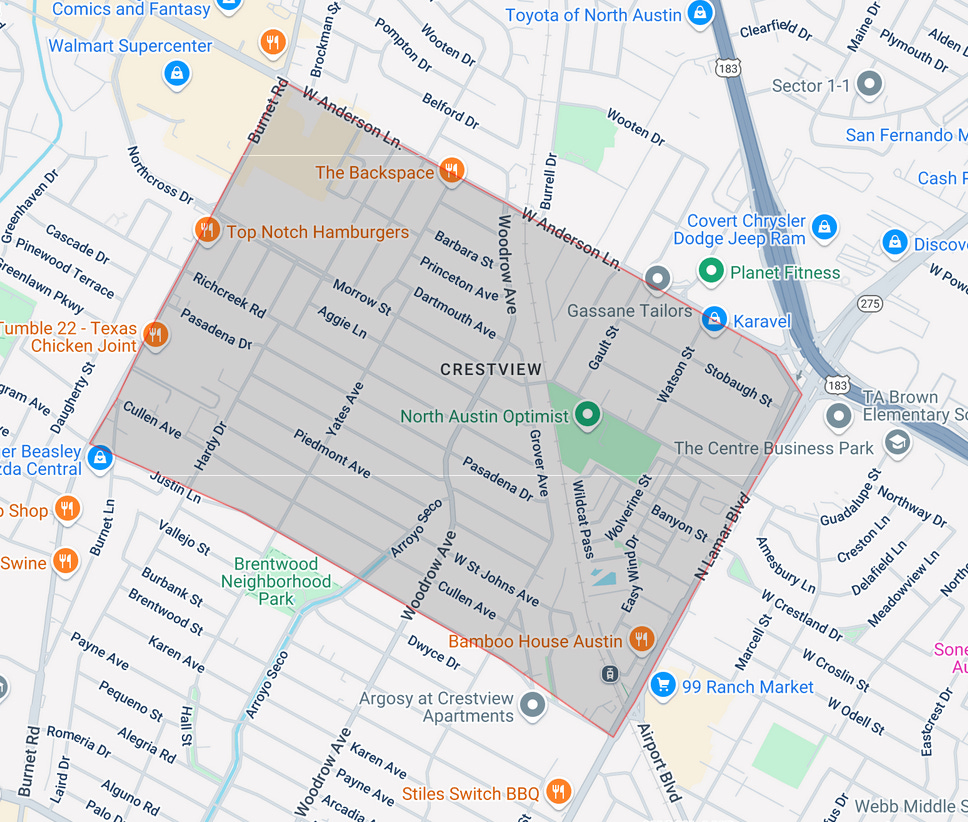

A few years later, my partner and I moved to Crestview, a neighborhood full of single-family detached houses and a few apartment buildings. Crestview was zoned for duplexes up to 2 stories, but historically there wasn’t enough demand to justify the construction of this housing type. As a result, most of the neighborhood remained single-family.

Census Tract 15.04 of Travis County, Crestview neighborhood

The cost of living in Austin had steadily risen through the decade of the 2010’s, but at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic demand to live in Austin suddenly surged. This led to one of the most extreme cases of skyrocketing housing costs in the United States - between February 2020 and May 2022, home prices increased by over 60%. As the market heated up, dozens of Crestview houses were torn down and replaced with boxy duplexes, while new high-rise condo and apartment buildings rose up alongside the existing apartments on arterial streets.

Single-family detached houses replaced with duplexes, before and after

New apartments on empty lots beside existing developments, before and after

A church redeveloped into new duplexes, before and after

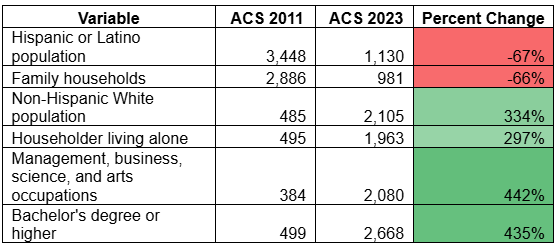

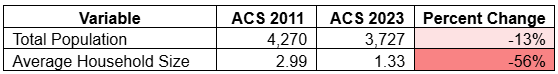

Between 2011 and 2023, Crestview saw some of the same economic trends as East Riverside. The number of occupied housing units increased about 50%, median home costs and household income increased 70-80%, and median home values nearly tripled.

Some of the same markers of a changing population appear: residents with a Bachelor’s degree or higher and employed in “Management, business, science, and arts occupations” doubled. Householders living alone increased 50%, and the number of non-Hispanic White residents increased as well.

But while the neighborhood got more affluent, the same evidence for displacement isn’t there. The number of family households also increased, and the number of Hispanic residents doubled.3 Average household size stayed the same. And finally, the overall population grew substantially, by about 40%.

This is the type of growth we need not be afraid of.

So What Makes Growth “Good”?

Ideal growth accommodates current residents while allowing room for newcomers and avoiding sharp spikes in rental prices. This sounds pie-in-the-sky, but it was achievable in Crestview and it’s achievable in Chicago as well. The secret is that the best growth is incremental.

Recall that Crestview was already zoned for duplexes, but few had been built due to low demand. Likewise, other Crestview parcels zoned for apartment buildings lay empty or underutilized. As the market heated up and demand increased, the zoning in place enabled additional housing to be built.

More apartments went up while current residents built ADU’s and replaced their existing houses with duplexes. This absorbed the new demand and accommodated an influx of new residents without wholesale displacement. And because Crestview had apartments across a range of ages, there wasn’t a cliff of older, inexpensive housing stock that all had to be replaced at the same time.

I experienced this firsthand. My spouse and I lived in an older apartment complex charging $1,600 per month for a 2-bedroom, while the nicer, newer complexes that opened up down the street from us charged $2,400 per month for a 2-bedroom. Newcomers who could afford the new complexes were thus accommodated while current residents who lived in older units (namely, my spouse and I) could stay put. Despite the surging property values, we didn’t face major rent hikes.

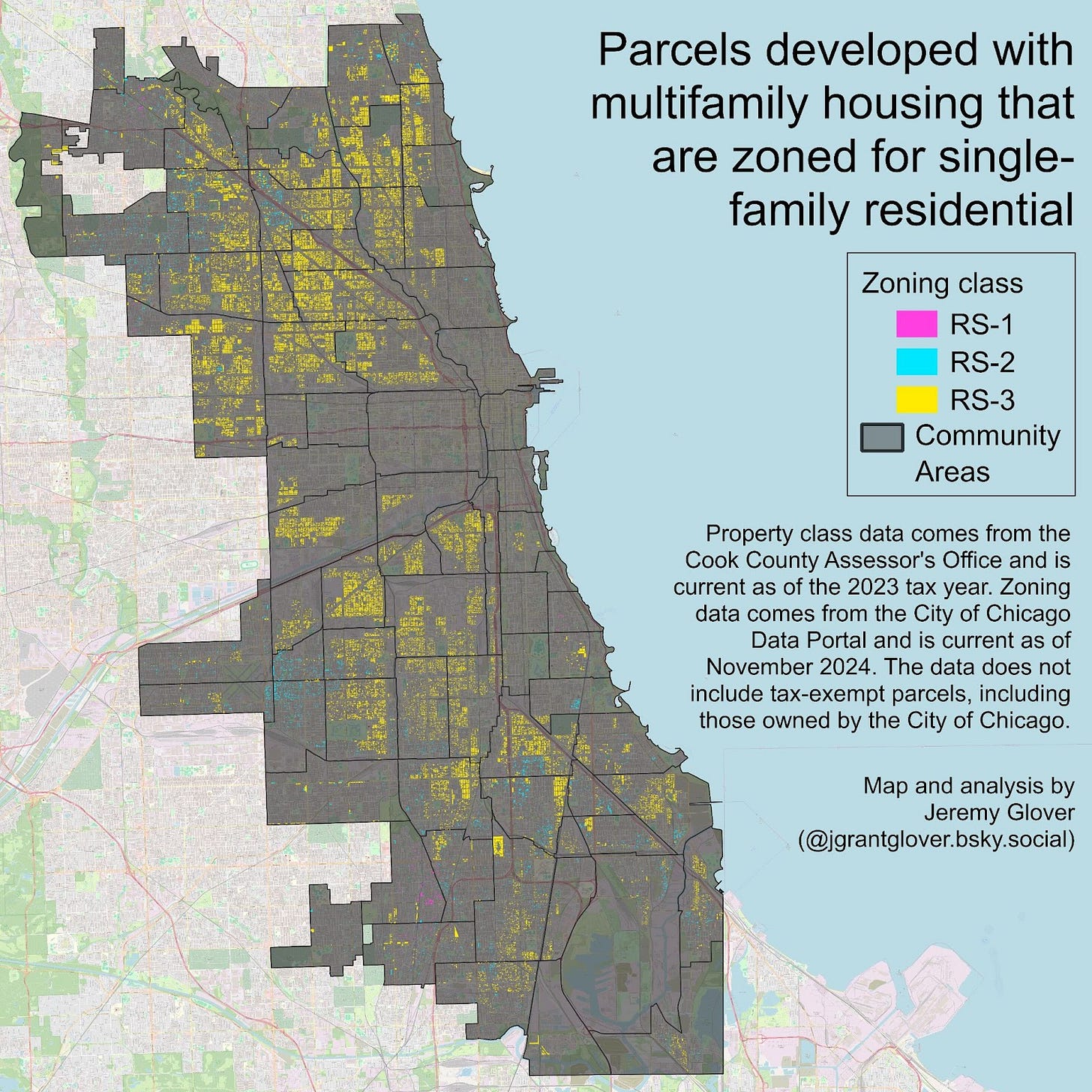

We can do this in Chicago, but that incremental quality is the critical missing piece. Most of our zoning and rules reflect a classic NIMBY position of no growth, ever. It is currently illegal to build the next increment of housing types in most neighborhoods. Worse than that, it is illegal to build many of Chicago’s existing housing types, such as 2- and 3-flats, in their current neighborhoods! I now live in just such a unit: my 3-story condo building, which sits in a neighborhood full of 2- and 3-flats, could not legally be built today.

A map of existing Chicago multifamily housing that is now illegal to build. Source: Jeremy Glover

To get to better growth, we can start by doing away with absurd bans on what’s already there. It should be legal to build the predominant type of housing stock in a neighborhood. The next step is to legalize the next increment of density. In a neighborhood of bungalows, a property owner should be able to build a 2-flat. Neighborhoods made up of 2-flats should allow 3- and 4-flats. Neighborhoods comprised of those should allow small apartment buildings and so on.

Note that none of this replacement is guaranteed to happen - if there’s no demand, the next increment of density won’t get built. Think back to Crestview before the COVID housing runup, full of single family homes despite being zoned for considerably larger units. But default legalization of the next increment allows for gradual growth to accommodate demand, which is the least disruptive means of accommodating new residents in an existing neighborhood.4

At the end of the day, cities, neighborhoods, and communities are living things. And living things change. If we make space for that change gradually, with the option to add a few more units in every neighborhood, we’ll make room for newcomers and long-time residents alike. That’s a recipe for a more sustainable, affordable, and vibrant city for everyone.

Noah Wright is on the board of the Chicago Growth Project.

Austin frequently tops new apartment construction charts where Chicago doesn’t even place in the top 20, for example.

I’m not including Black residents of Austin in this analysis because that’s another embarrassment entirely. All while being the fastest-growing large city in America, Austin actively lost its Black population. There’s plenty of writing out there on the macro-level trend as to why this was the case, but I can personally note that every Black friend and colleague of mine in graduate school said that they never felt welcome in the city. All of them moved elsewhere after graduating.

I don’t think it’s necessarily important that the ethnic mix of a neighborhood always remains exactly the same, but for the record, the proportion of Hispanic residents in the neighborhood also grew (since the population of non-Hispanic White residents grew by just 22%).

It’s also a recipe for better fiscal health. Austin manages to have much better funded pensions and a AAA bond rating.

We need to stop caring about the demographic composition of neighborhoods. No ethnic group has a right to any area, and I’m sick of people complaining about the rise of one and the decline of another. Just upzone, build housing and let people live wherever they want while turning a deaf ear to those who whine about “displacement” or “gentrification”.

This article really hits home 🏠 But seriously the part about Chicago needing to legalize it’s own existing housing stock is so true. I owned a three flat in Bridgeport by 31st Ave and Halsted and technically it violated the city code! Even Chicago needs to learn a few things from Austin and get with the growing YIMBY trend because restrictive laws make conditions more expensive and even more ethically segregated and unequal. The East Riverside project was classic gentrification but from reading the brief Wikipedia article about it sounds like the neighborhood is actually pretty nice to live in. And the other reality about the Chicago metro area is that it is still losing population so that has to be factored in to the comparison with Austin. Great article and I’m glad you did the reverse move!