To fight climate change, blue states have to grow

An abundance strategy for the state and local climate movement

The Clinton, Illinois nuclear power plant. In June 2025, Meta signed a 20-year Power Purchase Agreement with the plant’s owner, Constellation Energy. Source: Constellation.

We haven’t written much about climate policy around here yet, and I think that needs to change. Climate change remains a critical issue, and for the next few years any real progress will have to happen at the state and local level.

There were some important state-level wins during the first Trump administration. But the politics and economics around climate have changed a lot since. To secure lasting progress during the next four years, climate advocates will need to be a lot more disciplined about the issues the prioritize. That includes being a lot more focused on ensuring that blue states grow: adding jobs, people, and clean energy at a much faster rate than in the past.

The old playbook

The first time Donald Trump won the presidency, leaders in the climate movement pivoted to the state and local level. By 2017, more than 20 states and 110 cities (including Chicago) signed on to realize their commitments under the Paris Accord. California and New York passed laws requiring zero-carbon energy grids by 2045 and 2040, respectively.

A few years later, Illinois followed with the Climate and Equitable Jobs Act (CEJA).1 In addition to requiring a zero-carbon grid by 2045 and the closure of coal-fired plants by 2030,2 CEJA includes a range of targeted mandates and subsidies to ease the energy transition. Those efforts include steps to keep existing nuclear plants open, accelerate energy efficiency improvements, and ensure that the jobs and opportunities created by the transition were broadly shared.

This strategy worked pretty well. In 2020, the now-24 state coalition reported that it was on track to realize its commitments under the Paris Accord. In a period of relatively flat energy demand, investments in energy efficiency and renewables helped bring down carbon emissions at relatively limited cost. While the US as a whole wasn’t on track to meet its goals, those reductions helped ensure that states in the coalition cut emissions at twice the pace of non-coalition members.3 And the activity at the state and local level helped ensure that climate ideas and personnel were ready to act following Joe Biden’s 2021 inauguration.

This time is different

But things have changed since 2016. Emissions in blue states are a smaller share of the global total than they used to be. In 2023, California, New York and Illinois accounted for 1.7% of global emissions, down from 2% in 2016. That number is likely going to continue to decline, thanks in part to the policies laid out above, along with rising energy demand across the developing world.

That’s good news for the climate. But it also means that further emissions cuts in blue states will have a smaller direct impact on the climate outlook than they would have in the past—and that trend is likely to accelerate in the coming years.

In addition, thanks in part to the explosion of AI and cloud computing demand, we’re now in an era of rising demand for energy. PJM, the grid that serves the Chicagoland area, now forecasts that peak energy demand will jump by more than a third in the next 10 years.

Forecast Peak Energy Demand, for PJM, in Megawatts. Source: PJM Long-Term Load Forecast Report – January 2025

That has two implications. First – curbs on energy supply are likely to drive rising electricity prices. It’s no longer enough to turnover the generation mix and slowly bring down demand via energy efficiency levers. Now, without the ability to add significantly more power to the grid, Illinois is at risk of seeing electricity prices spike – hurting consumers and putting energy-intensive manufacturing jobs at risk.

We are already seeing early market signals of this. The price paid for spare capacity in PJM for 2025/2026 just soared to almost ten times the price for 2023/2024, ($269.92 per MW-Day versus $28.92). That’s also more than double the price in any year since 2015-2016.

Rising energy demand also increases the risk that emissions limits in one state simply result in higher emissions next door. Data center operators are making choices about where to site new assets. It might seem like a climate win to prevent a new one in Illinois. But what does that accomplish if it just gets built across the state line in Indiana, which burns twice as much coal as Illinois instead?

National climate action requires winning elections

Finally, Trump’s 2016 win didn’t turn out to be an aberration. There’s no path back to international climate leadership without winning the White House in 2028. And realistically, the White House alone isn’t enough. Congressional Republicans are planning to gut many of the subsidies and incentives embedded in the Biden Administration’s Inflation Reduction Act, strangling critical climate (and economic, and national security) investments in the process. If you care about the climate movement, you need to care about consistently winning enough congressional elections over a long enough time horizon to protect climate investments.

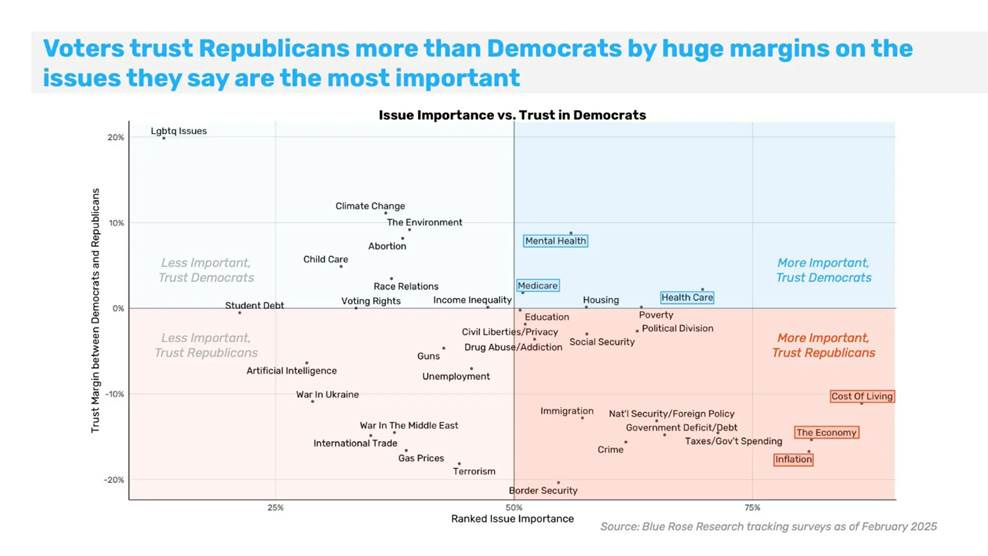

That doesn’t mean swing voters Ohio or Texas are paying attention to the details of climate policy in blue states. But voters do have a sense of how states like California, New York, and Illinois are doing overall. It will be hard for Democrats to claim to be the party of lower costs and faster growth if the states they lead tend to be high cost and slow growing.

Source: Blue Rose Research via Ezra Klein/New York Times

Following the election, Democratic strategists pointed to California as the party’s biggest liability, but this isn’t just a coastal phenomenon. Residents of Wisconsin and Michigan are more likely to Google Chicago than they are to search for New York, Los Angeles or San Francisco.

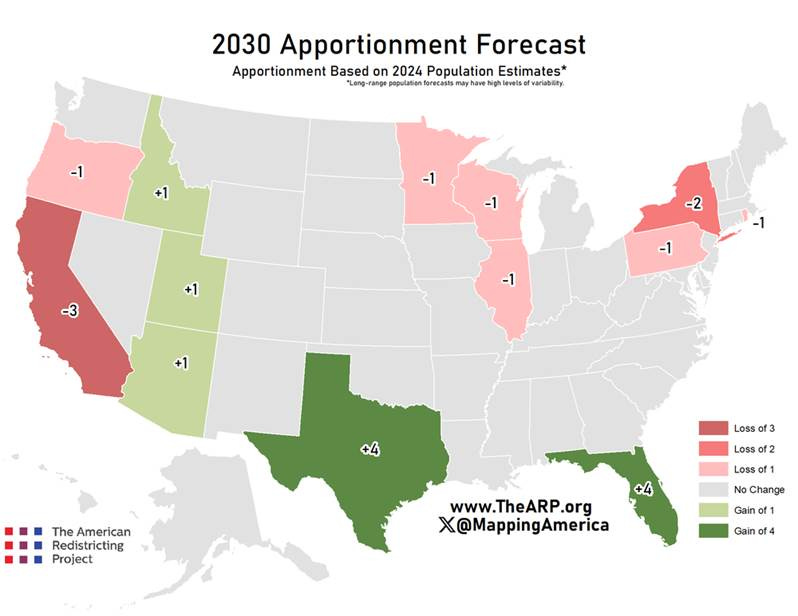

And even if you’re not convinced swing voters care about blue state dysfunction, a more mechanical threat looms. Based on current population trends, 10 seats in Congress (and their corresponding electoral votes) are set to shift from states that Harris won to seats that Trump won following the 2030 census. In 2032, a Democrat could win the traditional ‘blue wall’ states of Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin, and still be giving an early concession speech on election night.

Source: American Redistricting Project

None of this implies that Democrats must pursue maximally popular climate policies in blue states where they maintain control. But it does mean that economic and population growth in blue states is a climate imperative. In the current environment, climate policies that restrict growth in blue states will simply shift emissions and political power to red ones.

A pro-growth climate agenda

There’s no easy answer to these challenges. But I think it’s worth laying out a few pro-growth policy priorities for blue states and cities to have a maximally useful impact on the long-term climate outlook.

Prioritize innovation over state-level emissions targets

Blue states don’t have the same emissions profile as they used to, but they remain some of the most important centers of research and innovation in the world. US based inventions like photovoltaic solar panels, lithium-ion batteries, and nuclear reactors have been critical to cutting emissions not just here at home, but around the world. Even as our share of global emissions continues to shrink, our ability to influence global emissions remains a function of our ability to invent, commercialize, and scale better climate technology.

Of course, stretched state budgets are unlikely to pick up all the slack as the Trump administration hacks away at the US’s lead in research and science. But state and local leaders should be aggressive about protecting new R&D investments where possible.

Illinois’s recently announced TCCI Clean Energy Innovation Hub is a great example of the path forward here. The hub, funded with state resources, is designed to strengthen a key piece of the EV supply chain in Illinois (EV compressors) and support ongoing research on heat management in EVs. I have no idea how impactful it’ll end up being. But I do know that better EV technology developed in Illinois has the chance to make an impact on emissions well beyond state lines.

Accelerate approvals for zero-carbon energy production

While hard caps on emissions raise the risk that economic activity (and GHG emissions) simply shift to red states, faster rollouts of renewable energy have the opposite effect. Cost-competitive clean power not only helps grow blue state economies, but to the extent that it supports manufacturing jobs and data centers that would otherwise be built elsewhere, it has the chance to reduce total emissions well beyond the borders of Illinois or California.

But in recent years, red states have been blowing past blue states when it comes to new climate investments. Some of this is a function of cheaper land and labor. But permitting and regulatory approvals are another key variable. As researchers at Columbia’s Climate Knowledge Institute point out:

What about states that, unlike Democrat-led New Jersey and Illinois, are not exactly known for climate-friendly policies? Look no further than Texas. Despite offering minimal state incentives, the state has surged ahead of former solar leader California…

Texas’ streamlined permitting and interconnection processes enable solar projects to become operational notoriously fast. As a result, 2024 saw more capacity additions to the Texas grid from solar and battery storage than any other energy source… Republican-led Florida took second place for utility-scale solar additions in 2024, thanks in large part to its developer-friendly permitting policies. The Sunshine State’s Power Plant Siting Act simplifies the process and exempts any projects smaller than 75 MW.

Texas has some unique flexibility (and vulnerability) thanks to its separate and less-regulated energy grid. But it’s not surprising that states that have made it hard to build infrastructure are now struggling to build green infrastructure. Without faster approvals, blue states will continue to be left in the dust. In the first quarter of 2025, the six states with the greatest new clean energy installations were all governed by Republicans.

Source: American Clean Power Association

Nuclear power is another example. Here the challenge is not so much re-inventing the technology, but re-discovering the process to build those reactors cost-effectively. That requires building at scale and reforming the regulatory regime at the federal level.

While it’s still early, those are changes that the Trump administration appears to be pursuing. The changing economics of nuclear meant that reactors were already reopening with support from the Biden administration in Michigan and New York. Just last week, Meta announced an power purchase agreement with one of Illinois’ existing nuclear plants.

Nuclear also presents a unique opportunity for Illinois. We generate more nuclear power than any other state. Our combination of existing assets, engineering schools, and national labs means that we’d be extremely well positioned to lead a nuclear renaissance. But today the state has maintained a ban on large-scale nuclear reactor construction at the behest of state-level environmental organizations. As long as that ban remains in place, Illinois is likely to be left on the sidelines.

Prioritize density over building decarbonization

Cities are not just hubs of economic activity and innovation. They’re also one of our most efficient tools for fighting climate change. Density results in lower transportation emissions, and multifamily buildings also consume much less energy on a per unit than single family homes. And to the extent that dense cities in blue states grow, they also help to support the political power of Democrats in the House and Electoral College.4

CTA Rail Lines and Average Greenhouse Gas Emissions per Household (equivalent to Metric Tons of CO2/year.) Source: UC Berkely CoolClimate Network

There are certainly some climate organizations that continue to balk at density in other blue states, but those in Chicago generally get this one right. The harder conversation is around energy efficiency. For affordable developments, extremely high energy efficiency standards are a significant contributor to construction costs in Chicago and California. Not only does that mean more low-income families are displaced, but it also increases the odds that they’re stuck in older, substandard housing with much worse energy efficiency standards.

This problem also affects market-rate development. Last year, a committee convened by Illinois Governor JB Pritzker cited CEJA’s demanding new energy code as the primary state-level barrier to building new housing, and recommend pausing or extending the timeline for implementation.

Climate advocates and state and local officials need to take this tradeoff seriously. If we’re not willing to walk back standards that are likely to impinge on housing production (especially for low-income families that desperately need it), lawmakers need to pair them with dedicated funding to ensure that tighter building standards don’t end up subverting a broader climate agenda.

Prioritize transit frequency and reliability over electrification

This dynamic shows up around transit as well. In recent years, there’s been a push from climate advocates to electrify municipal bus fleets. This is a noble goal, but it’s gone extremely poorly – electric buses are far more expensive upfront, require a different maintenance process, can’t operate for a full shift without a lengthy recharging pause. That’s a recipe for less frequent and less reliable service.

A frequent and reliable diesel bus is a much more effective emissions fighting tool than an unreliable electric one.5 Transportation consultant Jarrett Walker notes that California’s electrification requirements are already resulting in service cuts – even though the climate benefits of adding five riders to an existing diesel bus are greater than the benefit of electrifying that bus. In Chicago, simply getting CTA ridership back to 2019 levels would have as big of an impact on CO2 emissions as electrifying the agency’s entire bus fleet.

This is another area where Illinois climate advocates have done a decent job. Climate organizations have been on the front lines of efforts to save Chicagoland transit agencies from brutal service cuts as federal funding winds down – while also demanding necessary reforms to governance and service. And while the proposed Northern Illinois Transportation Act did include a requirement to shift to zero-emissions vehicles, it also included a complete out clause if funding or infrastructure was unavailable.6

Fighting harder means fighting smarter

If we want to move the needle on emissions in the coming years, we’re going to need to be more ruthless about the issues and priorities we support. Climate research? Fund it. Clean energy? Approve it. Housing? Build it. Just about everything else? Let’s circle back in 2030.7

Unfortunately, while climate advocates remain conflicted, progress in Springfield has stalled. On almost all of these issues – including battery storage and nuclear power, housing and transit, lawmakers fumbled the bag badly and wrapped up the legislative session without action.

There are lots of good legislators still trying to address these issues. There’s also still time to act – hopefully in a supplemental session this summer. But if climate change is really a priority, advocates and lawmakers alike are going to have to lead with a great deal more focus and urgency than they’ve shown so far.

Illinois didn’t get moving until Governor Pritzker came into office in 2019, and CEJA didn’t pass until 2021. But it’s grounded firmly in the model of the other state climate actions here.

With the exception of municipally owned coal plants which need to be on a glide path to net zero emissions by 2045.

Interestingly, an evaluation at the local level found that most cities struggled to hit their targets. That’s not all that surprising – the smaller the jurisdiction, the harder climate politics become.

This again highlights the inanity of state-level emissions targets. If a family relocates from the South Side of Chicago to Northwest Indiana, emissions in Illinois will go down. But global emissions will rise!

It’s also a more effective tool for economic and population growth in blue cities.

Of course, there’s still the risk that a newly constituted agency tries to deliver on this mandate, since it’s technically encoded in legislation. We’d be better off if the mandate is dropped from any final transit reform and funding package.

Hasbro has yet to return my calls regarding Bop-It: Climate Edition

If you thought the 2025 PJM capacity auction was rough, just wait until you see what is about to happen for 2026.

The solar lobby and groups like CUB are quick to point out that PJM has a big and slow interconnection queue, but they won't tell you that solar, which makes up most of the queue, is one of the least valuable resources in the capacity auction. The ELCC is ~10%, and over time that will fall. So not only are we phasing out gigawatts of dispatchable firm resources, we are trying to replace them with something that is significantly inferior. All while load growth is exploding. Its a recipe for significantly higher prices, which will hurt lower income folks the most.

https://www.pjm.com/-/media/DotCom/planning/res-adeq/elcc/2026-27-bra-elcc-class-ratings.pdf

A good City That Works follow up to this would be a proposal for Illinois to exit PJM altogether.... We were our own balancing authority until Enron came around and 'deregulated' us. We have more than enough power to satisfy our own demand. The ComEd zone is a net-exporter of electricity every second of the year. Its the wider PJM region that aren't pulling their own weight, especially the mid-atlantic zones.

Who would have thought that one of the oldest high tech industry, nuclear power would be saved by the latest , AI???