Springfield might be getting serious about our housing crisis

Two bills with enormous promise for Illinois and Chicago

An Accessory Dwelling Unit in Lakeview. Legislation pending in Springfield would legalize these units statewide. Credit: Steven Vance.

We talk a lot about Chicago’s housing shortage – as of 2021, the city was short 120,000 affordable rental units. But Chicago's problems are embedded in a larger statewide housing crunch. Between June 2019 and June 2024, Illinois’ housing inventory fell 67% -- an indicator that properties are moving quickly and there’s insufficient supply available on the market. Statewide, median list prices rose 26% over that timeframe, outpacing overall inflation (23%).

This shortage hits vulnerable residents the hardest. When housing is scarce, higher income residents are able to fork over more for rent or a mortgage payment. Residents without means are most likely to be left in the cold. The best predictor of a city’s rate of homelessness isn’t the poverty rate, or social service spending, or weather: it’s the cost of housing. And study after study after study finds that housing becomes more affordable when there’s more of it to go around.

Expensive housing creates other problems. Higher rents and mortgage payments drain wallets and restrict other consumer spending. And when housing is expensive, it’s harder to grow. Residents are more likely to leave for cheaper Sunbelt states, and Illinois becomes a less appealing destination for in-migration. That makes it harder to retain workers, grow the economy, and cover our pension obligations.1

We think of this as a Chicago problem, but it’s also becoming an issue downstate. In Bloomington-Normal, where Rivian is investing $1.5 billion to build new EVs, median home prices have more than doubled since 2019. That poses a real risk to our chances of attracting more manufacturing jobs.

Source: Report of the Ad-Hoc Missing Middle Housing Solutions Advisory Committee, June 2024.

Beyond the dollars and cents, there are other benefits to growth. Lots of elected leaders talk about the need to stand up to stand up to Donald Trump. But Illinois is one of several blue states projected to lose congressional districts in the 2030 congressional redistricting. If trends hold, those seats (and their corresponding electoral college votes) will shift to fast growing red states like Texas and Florida. Unless something changes, a Democrat could win the ‘blue wall’ states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania and still be toast in the 2032 presidential election:

Source: American Redistricting Project

Springfield is part of the solution

Of course, if fixing this was politically easy, we wouldn’t be talking about it. A key part of the problem is that while the benefits of new housing accrue to the whole region, the perceived costs (traffic, noise, general aversion to change) are almost entirely local. I think those costs are often overstated, but it’s understandable that residents feel them. But when small suburbs (or individual wards) make decisions about development, hyper-local concerns dominate the discussion, and the larger benefits of more housing are ignored.

Each individual decision to restrict new development is barely noticeable on its own, but taken together they add up across the region. In a 2020 paper, University of Pennsylvania researchers find that these zoning rules raised the median cost of a quarter acre of land in Chicagoland by $63,000.2 We’re left with a region that is smaller, less affordable, and poorer than it would otherwise be.

Organizing at the local level is still important—we need every home we can get, and fights for specific projects can help build larger coalitions. But housing advocates in Illinois (and elsewhere), have started to focus more attention at the state level where lawmakers are better able to weigh the broad benefits of additional housing for the region.

That effort is starting to pay off. On March 20th two bills authored by State Rep. and potential YIMBY hero Bob Rita (D-28th) cleared the Illinois House’s Housing committee. If they make it through the Illinois General Assembly this session, and get signed by Gov. Pritzker, they have the potential to make a real impact on lowering the cost of housing in Illinois.

The first bill, HB 1813, legalizes the construction of Accessory Dwelling Units statewide. These are smaller structures, often called coach houses or granny flats, that are a crucial source of low-cost housing in neighborhoods that may otherwise be very expensive. They can provide an additional income stream for homeowners and are often a nice way to help older residents age in place, rather than being forced to move out of a neighborhood when a single-family home is too much to keep up.

The City of Chicago has had a very limited pilot for ADU legalization, but efforts to legalize ADUs citywide have been tied up for years. That’s meant that ADU production to-date has been subscale. Chicago Cityscape founder Steven Vance notes that statewide legalization may create the sort of predictable demand on a scale that would help foster a dedicated industry of ADU construction firms, bringing down costs and accelerating construction timelines.3

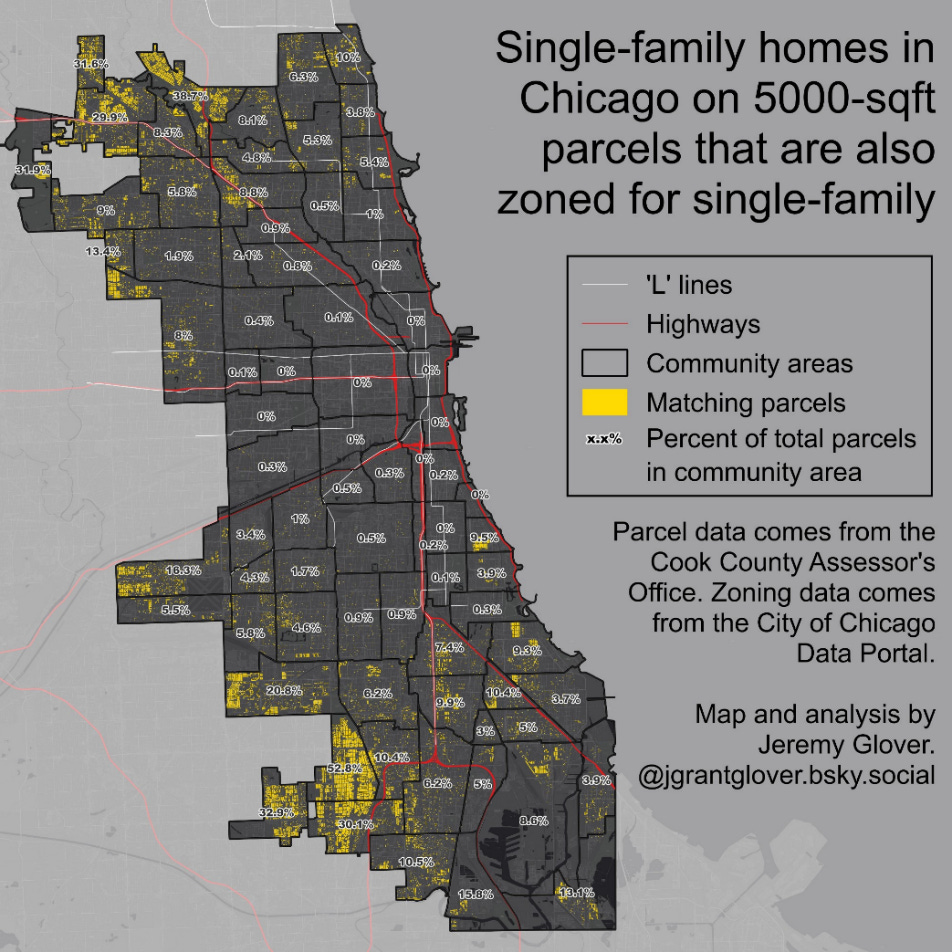

The second bill, HB 1814, would make it legal to build up to four units on any lot greater than 5,000 square feet. This would legalize the “missing middle” of our housing market: the 2-4 flats, townhomes and cottage clusters that add density and are generally much less expensive to buy and rent than single family homes. Single family homes could of course still be built (and in most cases, still will be). But it’d now be possible to add slightly denser, lower-cost housing in towns and municipalities where the demand exists.

While this is exciting, the missing middle bill still has room for improvement. As currently written, the 5,000 square foot lot means that the bill wouldn’t apply across most of the city – and would almost completely miss the neighborhoods on the North and near Northwest sides where costs are the highest. Ideally, the House would drop that requirement to 3,000 square feet before final passage.

Source: Jeremy Glover

But beyond that requirement, the missing middle bill is refreshingly simple—there aren’t other add-ons or carve outs. That’s important, because if we give local municipalities leeway, we’ll be back to the same twisted politics that makes regional decisions based on hyperlocal objections. If individual municipalities were able to demand overlay districts or impose additional standards to exempt themselves from the rules, for example, we’d quickly see them start to pop up in response to local NIMBY pressures.

It’s also a good thing that the bills don’t add affordability requirements to the newly legalized units. While well-intentioned, a wealth of research has found that unfunded requirements to rent new units at below-market levels dramatically reduces the amount of incremental housing that gets built. New housing is expensive, and if developers are unable to charge market rents, they’ll tend to build fewer, higher-cost units that they can charge full-freight for. In LA, Shane Phillips at UCLA’s Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies estimates that once affordability requirements exceed 20%, market-rate production declines so fast that no incremental affordable units are produced.4

In gentrifying neighborhoods, the city is already witnessing deconversions into higher priced single-family homes. We want to make 2, 3, and 4-unit buildings more appealing to build relative to single family homes. Requiring that 25% (or more) of the newly permitted units be rented at below market rates is a recipe for ensuring no new housing gets built at all.

A paradigm shift in our approach to housing

One of the great benefits of statewide legislation is that new housing will be spread out across high-cost regions, with minimal change to any single block or neighborhood. Instead, we’ll gradually see a steady scattering of additional ADUs, 3-flats and townhomes sprinkled across in-demand neighborhoods. Over time, that will add a release valve for housing markets with tight inventories and make life a little easier for renters and first-time homebuyers.

But in the long run, it’s hard to overstate just how important these bills could be. Advocates have been fighting for years to expand the ADU pilot across Chicago. Now in a matter of months we could legalize ADUs statewide. And the missing middle reforms embedded in HB 1814 could be an even more ambitious tool to add housing in areas where it’s sorely needed.

More fundamentally, these bills represent a new approach to housing in Springfield. Legislators are finally waking up to the state’s affordability crisis and reaching for a solution that adds supply at no cost to taxpayers. It’s also a great sign that Governor JB Pritzker is backing the changes – his office filed witness slips in support of both bills. As exciting as the specifics of the bills are, the emerging political consensus behind them is even more encouraging.

It’s time to work the phones

But we’re not across the finish line yet. In the coming weeks, lawmakers will decide if and how to bring these bills to the House floor for passage. It’s crucial that they move through without getting watered down—and ideally also drop the 5,000 square foot lot requirement on the missing middle bill.

You (yes, you!) can do two things to improve the chances that these bills pass. Neither one will take more than five minutes but they could make the difference between passage and failure.

First, call your state representative and senator. This process is easy, and fine to do outside of work hours if need be (they track voicemails – but calls of any kind count for a lot more than emails):

Go to the State Board of Elections District Locator and enter your address. Then scroll down to see the names of your State Representative and Senator.

Click on the globe icon underneath their name, to be redirected to their Illinois General Assembly webpage, which lists their contact information.

Use the number listed to call their office in Springfield, and indicate that you live in their district, support both bills, and want to see the minimum lot size requirement on the missing middle bill lowered. I’d suggest some version of the following:

“Hi, my name is [your name]. I live in [Rep/Senator] district, at the intersection of [Your Cross Streets]. I’m calling because we have a housing crisis in Illinois, and we desperately need to build more homes.

As part of that, I hope that [Rep/Senator], will support House Bill 1813, which legalizes Accessory Dwelling Units statewide. I also hope they will support House Bill 1814, which would legalize missing middle housing statewide – and that they will amend the minimum lot size allowed from 5,000 square feet to 3,000 square feet, in order to ensure the bill benefits Chicago.

Other than that change, I really hope these bills pass with no other amendments or changes that would reduce the amount of housing that they produce. Thank you so much.

Second, submit witness slips. These are public records of support that legislators and their staff track as the process unfolds. This process takes seconds:

(Suggested): Register for My ILGA, which will auto-populate your information when you submit witness slips.

Click on this link to submit a witness slip in support of HB 1813 (the ADU bill).

Enter your information (only the Name, Firm/Business/Agency, and “Representing” fields will be publicly visible). For Firm, enter "Abundant Housing Illinois" or whatever pro-housing group you're a member of. (or whatever else you’d prefer, but listing an official group gives these statements of support a little more oomph

In the ‘Representation’ field, write “Self”). In the ‘Position’ field, select ‘support’ and in the Testimony section, check “record of appearance only.”

Repeat the process here for HB 1814 (the missing middle bill).

That’s it! As of this writing, only a couple hundred people total have weighed in on these bills. A small number of A City That Works readers can make a real difference to their chance of passage.

Cause for genuine optimism

It’s easy to get negative around here. I can’t tell you how nice it is to write about some genuinely good ideas, with a real shot at passage for change. Representative Rita, Governor Pritzker, and a host of additional co-sponsors have made a gutsy call to stand up for two great bills. Now the rest of the Illinois General Assembly needs to get the message.

Our housing costs certainly aren’t the only thing contributing to the state’s demographic challenges. But they are an input to some of the other reasons Illinois is expensive (one of the key drivers of the cost of services is the cost of housing for workers, for example). And we have a lot more control over the cost of housing than the weather.

That’s in a 30 mile radius from the city center. The cost of zoning rules is much higher 15 miles in, and falls off pretty significantly once you get further out. For reference, a quarter acre lot is about 3.5 standard Chicago city lots, or 1.5 standard standard Evanston lots.

This also happened in California after that state legalized ADUs.

Notably, this covers unfunded affordability requirements. In Chicago, developers can receive tax breaks when they put affordable units on site. That’s created its own controversy (which I’ll try to get to later), but it’s a far better system than an unfunded inclusionary mandate, which just starts to throttle new housing production.

Some of the best things that happen to Chicago don't come from city hall. Instead, it comes from Springfield.

Advocates will get a lot more juice for the squeeze at the capitol. Zoning is the prime way that alderpeople wield power. They don't want to give up discretionary power. It will need to be taken away.

Urban planning should be done at the local level. Those people know the community the most. There is no one size fits all to zoning.

There is literally no evidence that adding more housing lowers housing costs. The most dense cities in America have the highest housing costs. Just like building more roads does not reduce traffic, merely adding housing units does not lower housing costs.