Should Chicago pension funds just buy the index?

One weird trick to make our pension funds a bit more efficient

In past posts, I’ve covered a lot of the problems with Chicago’s four pension systems. Today, I’d instead like to outline a proposal on how to make them work a little better: passive management.

The Basic Idea

At a high level, a pension fund is a large pot of money. On an annual basis, the fund receives inflows from employee and employer contributions, which grows the pot. It also makes distributions to beneficiaries, which shrinks the pot. But the pot doesn’t just sit in a bank account somewhere in the interim. Instead, each pension fund invests across a variety of asset classes to grow the pot over time. Like the vast majority of public pension funds, Chicago’s four pension funds1 are actively managed. Each fund has a team of investment professionals who decide where to put the fund’s money to achieve the best risk-adjusted returns possible. In addition to making their own decisions, they also often place those funds in the hand of other outside investment managers (including private equity funds, hedge funds, and a number of public fixed income or equity investment managers). From the City of Chicago’s 2023 annual comprehensive financial report2, here’s a look at their latest target asset allocations:

This is consistent with how the vast majority of public pension funds in the U.S. are managed, but not all of them. The Nevada state pension fund - the Nevada Public Employees’ Retirement System - is managed quite differently, as a 2016 Wall Street Journal outlined in detail:

Steve Edmundson has no co-workers, rarely takes meetings and often eats leftovers at his desk. With that dynamic workday, the investment chief for the Nevada Public Employees’ Retirement System is out-earning pension funds that have hundreds on staff.

His daily trading strategy: Do as little as possible, usually nothing.

The Nevada system’s stocks and bonds are all in low-cost funds that mimic indexes. Mr. Edmundson may make one change to the portfolio a year.

Instead of a team of professionals, Nevada’s entire system is managed by one guy. When money from contributions come in, it’s invested into the low-cost index funds along with the rest of their funds. When they need to make distributions, they sell a bit. There are no questions on asset allocation, or specific names to long or short, or new hot investment managers to onboard - you just buy the indexes.

This is the approach Chicago’s funds should adopt. At present, our strategy is a lot more elaborate - I counted over 80 distinct investment firms receiving management fees from the four funds as of 2023. That’s a lot going out the door. It stands to reason that if we can adopt an investment strategy that achieves similar performance but keeps those funds invested, it would be better.

How would this impact returns?

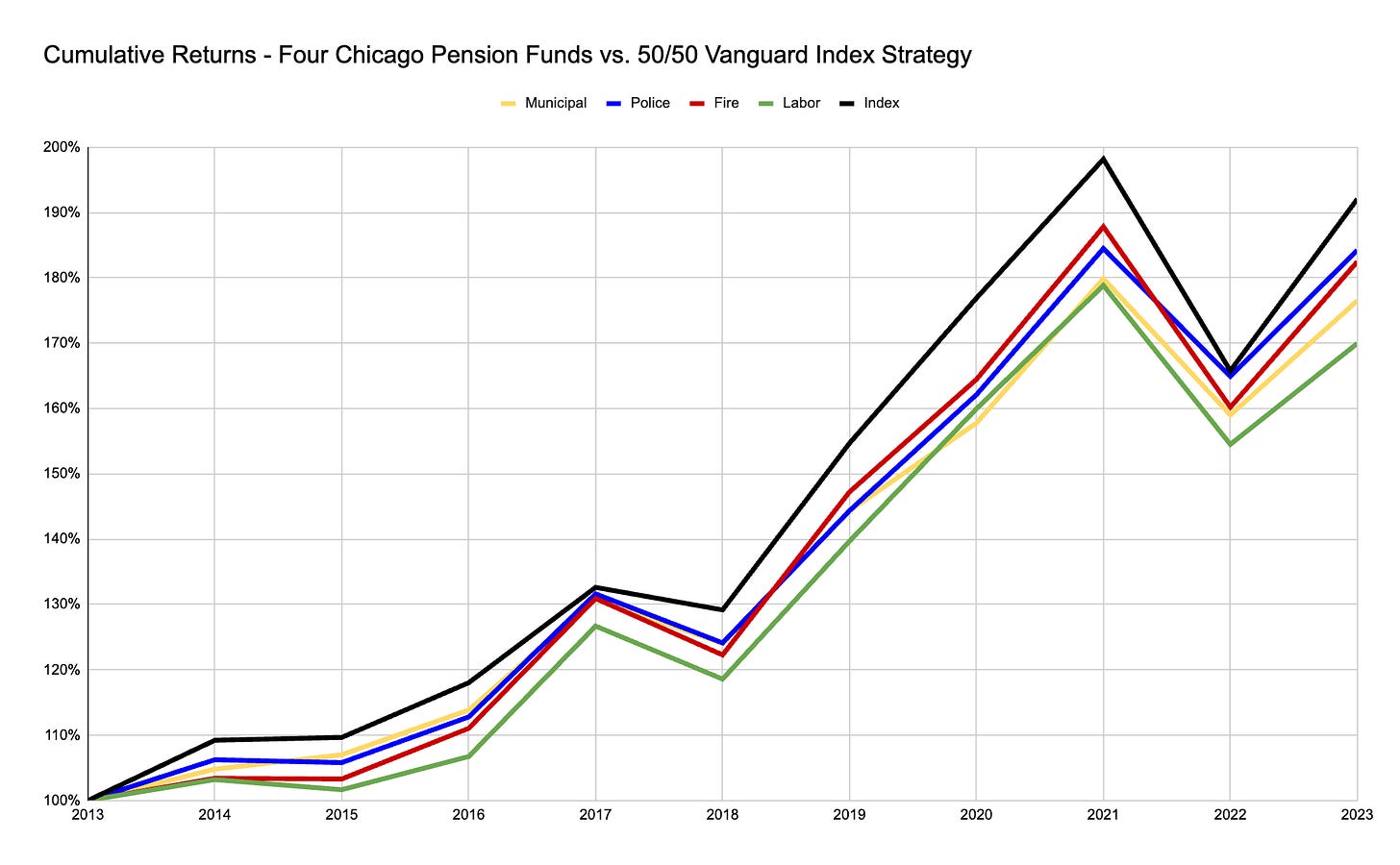

So - can we achieve a similar performance? Yes: simpler doesn’t have to mean worse returns. To approximate a very basic index fund strategy, I went to Vanguard’s website to get the annual performance returns for their total stock market and total bond market funds. I combined these two with a 50/50 rate (which strikes me as a pretty conservative investment strategy), then compared those returns to the last 10 years’ fund rates of return published by each of the four pension funds in their 2023 audited financial reports. Here’s how they compare on a year-by-year basis:

And how that adds up over the decade (indexed relative to 2013):

Again, I’d like to stress this is about the most simplistic and basic thing I could possibly do - but that 50/50 index strategy is enough to generate a better annual return than any of the four pension funds while still showing a similar annual volatility. The benefits you’d expect the funds to be receiving from their more diversified portfolios in real estate or private markets doesn’t seem to be translating into meaningfully better returns - at least not factoring in the cost of those investments (or the cost of their active public investment strategies alongside them). I’m cognizant that there are a lot of other caveats to make here,3 but I think the fact that a simple 50/50 strategy is even competitive is a pretty good point in its favor.

The upside of simplicity

That simplicity would come with a few other very straightforward benefits to Chicago, too. Start with direct cost savings. Here’s a look at exactly how much the four systems have been paying out each year in active investment management fees:

Over the past decade, that’s nearly half a billion in investment expenses we’ve incurred. That’s a lot! You can’t eliminate these fees altogether - at a bare minimum you’d have some custodial fee on the assets, and even index funds have some kind of expense ratio - but we could do away with most of them; the WSJ article noted that Nevada’s outside management bill is about 1/7th that of the average public pension plan’s. Getting rid of 85% of these fees would mean more than $360 million over ten years - and over $500 million when you account for the compounding investment returns those additional funds would generate. This won’t fully solve our pension problem (I trust you can do the math that $500 million is a lot smaller than $37.2 billion), but it’s still a good dent, equivalent to a couple of the supplemental pension payments we’ve been making each year to chip away at the problem.

Simplicity comes with other benefits as well. Liquidity strikes me as an obvious one. The assets I’m talking about here (Vanguard index funds) are some of the most liquid instruments available in modern financial markets, while many of our funds today also include significant portions in illiquid assets such as private equity or real estate.4 Under normal circumstances, that’s not a significant concern for pension systems; it’s actually what you want - their long-duration liabilities and stable asset base are usually tailor-made for targeting less liquid asset classes and the premium returns they usually carry. In the case of our funds, however, I’m actually concerned that our low funding rates have threatened our ability to enjoy that privilege, given how much of the portfolio may require redemption to pay benefits at any given point in time. In light of that, sticking to a simpler, more liquid asset strategy strikes me as prudent.

It would also help stave off any (for lack of a better term) shenanigans around where exactly the funds should be investing. Just last year, real estate developer Sterling Bay tried pitching the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund on investing over $300 million in the Lincoln Yards development in an effort to reenergize the stalled project (they said no). Chicago being Chicago, I’d imagine that other ‘opportunities’ like this pop up more frequently than we’re aware. While I genuinely have full confidence in the investment teams of each of the pension funds to manage their strategies prudently on behalf of their beneficiaries, it seems to me that eliminating the potential for such conflicts of interest altogether would be a really nice side benefit of this approach.

Some logistics

I’m not naive enough to suggest we could off-board all of those investment managers tomorrow if we wanted to. A lot of those private investments are likely locked up in longer duration funds; they’re not things you can - or would want to - unwind tomorrow. Many of those public market investment managers might have contracts we’ll need to deal with too. All of that said, transitioning away from this current strategy is a good idea.

On the liquidity question, you may also wonder whether there’s a risk in putting all our eggs in only a couple baskets. I’d note that Vanguard as a whole has over $7 trillion in assets under management - so adding the four Chicago funds’ combined $11 billion would be a drop in the bucket for them. Moreover, the average daily volume of the two ETF equivalents of those two mutual funds (VTI and BND, respectively) equate to around $800 million and $400 million, respectively - which again strikes me as plenty sufficient for any daily liquidity needs we’d have.

The Bottom Line

Shifting the city’s four pension funds to a passive investment strategy has the potential to save $30 to 40 million per year in outside investment management fees without degrading investment returns.

That is a change worth making.

The Laborers’, Municipal Employees’, Firemen’s, and Policemen’s Annuity and Benefit Funds.

Page 97.

Two offhand: My “index fund” strategy ignores any investment expense, which is unrealistic; second, the money-weighted returns from the four funds aren’t quite an apples to apples comparison with a time-weighted return from Vanguard. That said, I think 50-130bps of outperformance is still a pretty significant win for the index comparison.

See that first chart on asset allocations again - by my math, the four funds have roughly 20-30% of their investments in less liquid asset classes.

This is a very good idea, especially knowing that our pension funds have a deep history of making questionable investments. I suppose the risk would be mitigated by the timing of making these changes.

The only downside I see is the short term risk of investing the way when markets are at their highest- we can expect a downturn after the election.

Pretty outrageous that all of the "management" of these funds benefited the managers a whole lot more than the pensioners.