Source: C. Holmes, Flickr Creative Commons Attribution

We’re excited to publish this piece from Justin Erb, a Chicago-area prosecutor. The views expressed in this article are very much his own, and do not represent the views of his employer.

And as a reminder, we have another City That Works meetup next week! Come join us Thursday, July 17th at the Jefferson Tap, from 5:30-8:30. You can register here (attendance is free).

Most people who see police lights and sirens in their rearview mirror pull over right away. Some people don’t, and those people are committing a crime called fleeing and attempting to elude a police officer. We’ve all seen dramatic helicopter footage of police chases, and if you’re like me, you assumed that anybody unfortunate (or unskilled) enough to be caught at the conclusion of the chase is in for a lengthy prison sentence. In Illinois, that’s not the case. In fact, fleeing and eluding is a misdemeanor.

This is a serious policy mistake. In fact, it borders on encouraging people to flee from the police.

Fleeing from the police is a really big deal

Running from the police is one of the most clear, obvious criminal actions somebody can take. First, having to obey a police order is a necessary predicate to any sort of criminal justice system. Criminal law exists to coerce individuals to maintain some basic standards of conduct. If complying with our criminal code is optional, it undermines our ability to enforce every other rule.

Second, a car chase can be incredibly dangerous for the police, the driver, and for anybody that happens to be on the road. About 350 people die a year in America due to police chases, and about half of the people killed or injured in these chases are innocent third parties. In Chicago specifically, police chases have often resulted in horrifying tragedies, killing or maiming third parties, and also leaving the city on the hook for millions of dollars in settlement payouts.

Finally, when people decide to flee from the police, particularly for minor traffic offenses, there’s a good probability that they are in the process of committing another crime they are trying to conceal. This could be as simple as driving without a license, or as serious as driving with an illegal weapon or some large quantity of drugs. In at least some of those cases, offenders may be making the calculated decision that it’s worth the risk of picking up a new crime to avoid getting caught with a more serious one, or worth just buying some time to hide or destroy evidence.

For fairly obvious reasons, it is tricky to get reliable data about how often people are fleeing from the police to obfuscate or destroy evidence of other crimes. However, at least in California in 2020, about 16% of all police pursuits were initiated because the police tried to pull over a stolen car. In Pennsylvania, about 20% of the reason for the stop was either because the vehicle was stolen, or some other felony. According to the San Francisco Chronicle’s database for fatal police chases, about 20% of the chases were initiated because the driver was wanted for some sort of violent offense. Furthermore, when the driver was apprehended, about 17% of the time, the driver was subsequently charged with a more serious offense, including felony drug violations, felon in possession of a firearm, or attempted murder.

All this is to say, on the continuum of crimes, fleeing and eluding is a bad one. It’s dangerous, it erodes the functioning of the criminal justice system as a whole, and it lets people get away with even more serious crimes. It should be treated like the serious offense it is.

It’s easier to flee from the police than you think

But even though this crime is a uniquely bad one, the odds of getting caught are surprisingly low. The Chicago Police Department has a fairly stringent balancing test they must apply before engaging in a vehicle pursuit. The test requires an officer to weigh the benefits of apprehending a subject with the danger created by a vehicle pursuit. In the vast majority of cases, particularly for most traffic offenses, officers and supervisors frequently choose not to pursue the vehicle. In 2023, CPD reported 2,564 incidents where drivers refused to stop or fled from police. CPD only pursued drivers in 15% of those cases.

There are still ways to apprehend people even after they successfully flee, especially with license plate readers, surveillance cameras, and clever teamwork, but there’s no question the odds are much worse than just chasing the person. While catching someone after the fact is better than not catching them at all (or having them T-bone an innocent bystander), it comes with its own challenges. To secure a conviction for fleeing and eluding, prosecutors need to prove the identity of the particular driver, not just the owner of the vehicle.

Even if the police caught a license plate, was able to track it to the registered owner, and showed up on their front door the next day, that would not be enough for a conviction. The State would have to affirmatively prove that somebody didn’t borrow or steal the owner’s car. That in all likelihood would require the police officer to identify the driver based on his or her observations.

When you’re driving, how often are you seeing the faces of the drivers next to you? What about the drivers in front of you? Imagine trying to do that during the chaos of trying to pull somebody over who is actively trying to avoid you, and then affirmatively identifying that person hours or days after. It can and has been done, and A City That Works has written previously about ways the city could be better at it. But for obvious reasons it is not and probably never will be as effective as just catching the driver.

Even if you get caught fleeing and eluding, the punishment probably won’t be too bad

Even if prosecutors do secure a conviction, a defendant will likely only receive a slap on the wrist. In Illinois, fleeing and eluding is a Class A misdemeanor. That’s the same penalty as retail theft under $300, buying a beer for somebody under 21, and owning a crack pipe. The absolute maximum term is 364 days in prison, but there is a next to zero chance that you’re actually going to get anything close to that sentence.

The most likely outcomes are that a defendant would be sentenced to supervision, or to two days in prison. If the sentence is supervision, a defendant simply has to avoid being caught committing any other crimes for the next year. If a defendant is sentenced to two days in prison, they’ll generally be released on the day of their sentencing, because time spent in jail after an arrest counts as time served. The defendant’s driving license is also suspended for 6 months. That’s hardly the serious time you might expect.

There are some ways that fleeing and eluding can be a felony. It becomes a Class 4 felony after the third conviction. It also becomes a felony if there are certain aggravating factors - the defendant breaks the speed limit by over 21 miles per hour during the chase, the chase results in bodily injury to “any individual,” causes over $300 in property damage, breaks two or more traffic control devices, or the defendant hides or alters his plates in some manner. Doing any of this once is a Class 4 felony as well.

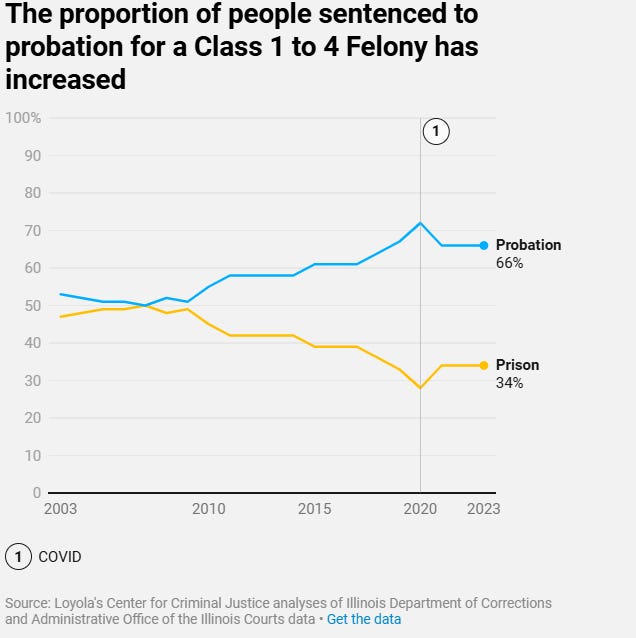

The sentencing range for a Class 4 felony is 1-3 years in prison, but it’s much more likely that a defendant would be sentenced to probation. A second or subsequent conviction is a Class 3 felony, which can be up to 2-5 years in prison, but it also is much more likely than not to result in probation.

Source: Loyola’s Center for Criminal Justice

Keep in mind that even if convicted and sentenced to prison, due to time spent in some form of pretrial detention and “good time” credit, the defendant would spend a fraction of that time actually inside prison. Across all felonies in Cook County, person who is denied pretrial release after being charged with a felony spends about 8 to 14 months in jail or electronic monitoring.

The law can’t reward drivers for the fleeing police

Illinois more or less has set up a system where it actually makes sense to flee from the police. There are two potential solutions to this problem - lowering the odds that offenders can successfully escape, and increasing the penalties associated with fleeing when they do get caught.

The first approach is preferable for a number of reasons. Most importantly, a lot of research indicates would-be offenders do not make rational cost-benefit decisions in the seconds before committing a crime. To the extent that offenders are thinking about the consequences, the certainty of punishment matters a lot more than the severity of punishment. But that brings us back to the tradeoffs between apprehending offenders and violent, deadly car chases that also generate major settlements. Figuring out the exact mix of technology, targeted chases, and just letting people go is beyond the scope of this post.

But while harsher sentences are rarely the answer for other crimes, fleeing and eluding is an exception. Fleeing from the police endangers the lives and safety of police, not to mention the regular people who happen to be on the road. It’s indicative of guilt of even more serious crimes. It should be treated like the serious crime that it is. And even if more severe sentences don’t *generally* deter crimes, the size of the gap here between harm and the current punishment is so large that if even some deterrent effect could be realized, it’d be worth pursuing.

Punishments Should be Smart and Targeted

First, we should upgrade fleeing and eluding to a felony, and aggravated fleeing and eluding to a more severe class of felony. As we’ve already established, certainty of conviction is a bigger factor in deterrence than severity of punishment. It does not follow, however, that greater punishment does nothing for deterrence.

The legislature should also take care to give prosecutors and courts more options, not fewer, when crafting these new penalties. The majority of people who commit fleeing and eluding are, in all likelihood, fine people who panicked and made a bad decision. For these people, the legislature should create some equivalent to the First Time Weapon Offender’s Program, where recipients have their background cleared if they go one year without picking up a new felony. Furthermore, State’s Attorneys should be encouraged to liberally downgrade fleeing and eluding charges to misdemeanor attempt charges.

The main advantage of making fleeing and eluding a felony is that it eliminates the current environment where it makes more sense to run from the police than to pull over for some cohort of people, normally the most dangerous felons. I’m not suggesting that anybody, particularly multi-time felons, are doing this mental calculation every time they are pulled over. But they probably have at least a vague sense in that moment of what the likely consequences of not pulling the car over are, and Illinois’s policy should not be to make fleeing the obvious choice in that circumstance.

Beyond deterrence, there’s an additional benefit to making fleeing and eluding cases a felony. In situations where an offender escapes rapidly without a chase and ditches incriminating evidence of other crimes, the current system doesn’t guarantee much of a punishment even if they are caught later via a camera or license plate reader. Ensuring that fleeing and eluding itself merits a felony ensures that society has an option to incapacitate dangerous offenders who do use the current no-chase laws to evade other crimes.

Second, there should be consequences for owners of vehicles that happen to be involved in fleeing and eluding incidents (provided that they’re not reported as stolen). For example, Illinois could make it so any vehicle involved in a fleeing and eluding incident is automatically forfeited. This way, the State would not have to prove any person in particular was the driver, increasing the certainty of punishment without any further investment.

This law is already on the books for the aggravated form of fleeing and eluding, and should be extended to the misdemeanor version as well. And although some people might prefer to lose a car than to be caught with a gun or drugs by the police, it still is not a pleasant outcome. Illinois could similarly suspend the driver’s license of the registered owner of any vehicle involved in a police pursuit automatically, even without a conviction under the same logic. This policy could have some positive downstream effects of other crimes where it is easy to identify the vehicle but not the driver, such as such as hit and run incidents.

Any of these reforms should come with some sort of release valve for innocent or indigent car owners. Nobody would benefit from a situation where a person whose car is stolen gets their license suspended a month later when the thieves use their car to outrun the police, for example. This could be in the form of a hearing where the vehicle owner can provide some small amount of evidence they were not the ones driving that day, or the impound or license suspension could be for a fairly short period of time. So long as the punishment is swiftly enacted with a high degree of certainty, the actual punishment can be fairly light.

Driving is a privilege that should not just be given to those who show a minimum technical competency, but for people who society can trust to pilot a multi-ton machine that can and regularly does kill people. Part of that privilege is having the fortitude and coolheadedness to just pull over when you’re told, and not to risk random people’s lives because you panicked. That is simply not a crime on the same level of seriousness as owning a crack pipe, and society’s outrage at this activity should be reflected in its laws.

A rational and well-thought-out piece by someone who sees the effects of these situations up close. Thank you.

If I could add one more suggestion - fleeing is currently a "non-detainable offense" under the SAFE-T Act, and this seems like a mistake on the legislature's part considering fleeing inherently demonstrates the offender's willingness to run from justice.

I'm not saying every instance deserves pre-trial detention, but judges and prosecutors currently have no ability to make these subjective determinations based on case specific context. Allowing the case to be made that specific offenders obviously pose a risk to the public seems like a good idea given the act clearly shows a willingness to ignore efforts to hold them accountable for their dangerous actions - intentional or otherwise, not to mention the risks they put on the public during these dangerous actions they willingly took.

While some will argue that electronic monitoring should suffice, I would simply offer that that system has consistently been found to be woefully ineffective due both to technical issues and judicial resource constraints.

reactionary nonsense