Chicago’s state capacity crisis

It’s getting harder and harder for government to get things done

Each padlock added to the Pont des Arts bridge in Paris has a love story behind it. But if the Paris Government doesn’t regularly cut them off, the bridge will collapse under their weight. Photo: PxHere Creative Commons license.

In March, Chicago’s Progressive Caucus made a painful observation: voters believe that city government just isn’t functioning. Following the defeat of the Bring Chicago Home campaign, which would’ve raised real estate transfer taxes to combat homelessness, the caucus observed that “[v]oters who opposed the referendum told us that their vote represented their current distrust, frustration, and disappointment with government… Chicagoans deserve and transparent and responsive government that gets things done.”[1]

It's hard to argue with them. On issue after issue, it feels like government is either performing worse than it has in the past, or we’re spending a lot more for the same results:

Housing: Chicago has a shortage of affordable 120,000 units (and rising), but efforts to redevelop Chicago Housing Authority properties have been mired in delays. Costs for new city-funded affordable housing now average $600,000 per unit.

Public Safety: Thankfully, violence is trending down this year, but homicide rates are still far higher than in the 2000s. Police only make arrests in 20% of fatal shootings, and total arrests for violent crime fell 79% between 2006 and 2021.[2] Arrests certainly aren’t the best indicator of police effectiveness—real public safety involves fewer crimes committed in the first place. But if arrests are falling while homicides are up, something’s broken.

Transit: The CTA has cut schedules repeatedly, but still can’t deliver on promised service as it faces a looming fiscal cliff. Meanwhile, the planned Red Line Extension is projected to cost seven times more per mile than the Orange Line, which we completed in 1993 (that’s after adjusting for inflation).[3]

Education: There are 100,000 fewer students enrolled in Chicago Public Schools than there were 20 years ago, even as district spending continues to rise. Reading scores have only now recovered to pre-pandemic levels, while math scores remain below 2019 levels.

Many of these challenges have been worsened by external factors like the pandemic and inflation. But a key piece of the problem is coming from inside the house. City government is being slowly strangled by layers of process that have accumulated over decades. Many of these constraints are well intentioned correctives to past misdeeds. Anti-corruption checks are important, affordable housing should be high-quality, and accountable policing is fundamental to long-term public safety. But without any effort to rationalize the constraints we continue to add, we have a crisis of state capacity: a government unable to get things done.

I’ve written about one of our most fundamental state capacity problems before: it takes 6 months to hire for roles in city government. But HR is just the start. Procurement processes can take years, and delays hamstrung efforts to feed asylum seekers. Technology systems are a “spaghetti mess,” heavily reliant on customized, outdated software, and propped up by an understaffed and aging workforce. Finance is also a challenge – the city can take years to bill vendors for special events.[4]

Those are the deep, broken systems that hobble government at every level. Then there are the issue-specific constraints that have steadily built up:

Since 1969, major projects receiving federal funds are required to submit an Environmental Impact Statement under the National Environmental Policy Act. In 1985, the CTA’s Final EIS for the Orange Line ran 378 pages. The 2022 Final EIS for the Red Line Extension is 50 times longer, at 17,899 pages. That’s for a project that’s half as long.

Higher costs for new affordable developments are driven in part by “ever more rigorous government standards for accessibility, sustainability and design,” according to reporting by Crain’s.

The consent decree requires far more documentation on the part of Chicago police officers, but the Office of the Inspector General has found that records management at the department is a mess.

If this is depressing to read about, imagine how difficult it is to try to work through. There are an enormous number of talented, caring, and capable employees working for the city. But over the last few decades, city staff have spent more time fighting systems designed to slow them down and less time on the work that led them to public service in the first place. That creates a slow, vicious spiral: as public sector work becomes less rewarding, high performers leave, or never pursue a career in government in the first place. And with an overstretched, less capable workforce, more mistakes happen – inviting more rules that further hamstring public servants.

Some people think this is a feature, not a bug. This view is common on the right, where cascading government failures are used to justify more constraints and budget cuts. But in Chicago, you can also see this style of thinking on the left, with activists pointing to our poor public safety record as justification to defund the police. These folks are in the minority, and they’re also wrong. You might be able to go it alone elsewhere, but a modern city can’t succeed without functional infrastructure, a decent social safety net, and adequate public safety.

Despair nationally, act locally

These problems are not unique to Chicago. In 2022, Ezra Klein offered a blunt assessment in the New York Times:

When I go looking for ideas on how to build state capacity on the left, I don’t find much. There’s nothing like the depth of research, thought and energy that goes into imagining health and climate and education policy. But those health, climate and education plans depend, crucially, on a state capable of designing and executing policy effectively. This is true at the federal level, and it is even truer, and harder, at the state and local levels.

That is starting to change. Jennifer Pahlka’s excellent 2023 book Recoding America takes readers through the challenges of fixing broken digital services, from Healthcare.gov and veteran’s benefits to food stamps and state unemployment insurance programs. She also has a great Substack on the topic. And she’s not alone. In the last few years, there’s been growing attention to this challenge of state capacity from think tanks across the ideological spectrum.[5]

But Klein is right that the state and local versions of this problem haven’t gotten nearly enough attention. It’s where a huge share of domestic policy gets implemented. Unfortunately, red tape tends to snowball--federal funding comes with its rules and reporting requirements that pile on to the dysfunction that state and local government are already subject to. And while staff in local governments can be driven up the wall by those rules, it’s hard to push back—loudly complaining about funding constraints isn’t conducive to receiving any more dollars.

Focusing on state and local challenges could also bring faster progress. Mayors are often the most directly exposed to the wrath of voters when the snow isn’t plowed or trash isn’t picked up. They should have a greater incentive to fight for more governing capacity. And because the policy to implementation cycle generally moves faster, there are more opportunities to experiment with what works.

A place to start

There aren’t easy answers to these challenges, and this post is more of a strangled cry for help than a detailed set of solutions. But here are a few ideas:

Make state capacity an early-term priority: Nobody gets re-elected for speeding up hiring or procurement, but without fixing those issues, ribbon cuttings and policy accomplishments won’t happen in time for re-election. But by year two or three when these problems start to bite, it’s too late.

Hold officials accountable for outcomes and give them flexibility on process: Too often, government officials face one-way incentives: if a process isn’t followed, or a mistake happens, they’re likely to end up in the paper. But leaders are rarely recognized for delivering more efficient public services or taking measured risks that end up paying off. Rebuilding state capacity will require holding public servants accountable for better outcomes, but then giving them more flexibility on the approach to get there.

Don’t rely on new technology to save broken processes: As Pahlka’s book notes, one of the key reasons technology rollouts fail in the public sector is that policymakers insist that technology perfectly captures the rules and edge cases imagined by legislation and implementation guidance. But that’s never how technology implementations work in the private sector—there is a necessary iterative process, where requirements are adjusted and prioritized to build something workable within technical and resource constraints. To make technology modernization efforts successful, the city needs to simplify and update processes (or have non-technology workarounds for edge cases), rather than simply shove broken systems into the cloud.

Approach centralized services with caution: It can seem appealing to centralize core functions, like HR, finance, and procurement. But while the mission or meaning of work matters to all employees, it’s an especially important part public service. A finance administrator who sits next to their colleagues in the Housing department is likely to carry the culture and values of their department. An administrator working in a central department three floors below, handling reimbursements from a half dozen different departments may not.

Highlight the upstream constraints driving government dysfunction: While there’s coverage of many of the consequences of these state capacity challenges (much of which I’ve linked to here), there’s remarkably little attention paid *why* core city systems work so poorly. It’d be a real public service if reporters dug further on the longer-running causes of the city’s hiring, procurement and technology challenges, and if advocacy organizations that focus on specific issues spend a little more time on the upstream causes of poor performance.[6]

These suggestions might sound fanciful given the city’s current challenges, but there are positive efforts to build off. When the city switched from ward-based to a grid-based garbage collection, Streets and Sanitation was able to use 60 fewer garbage trucks and save $30 million a year. When Streets and San finally won approval to move away from the old request-based tree-trimming, the city started trimming more than twice as many trees per year. In a similar vein, the City’s new Housing and Economic Development Bond will simplify the Kafkaesque process of segregating city development funds by TIF district. Mayor Johnson’s Cut the Tape initiative could make it easier for affordable and market-rate developers alike to build new housing.

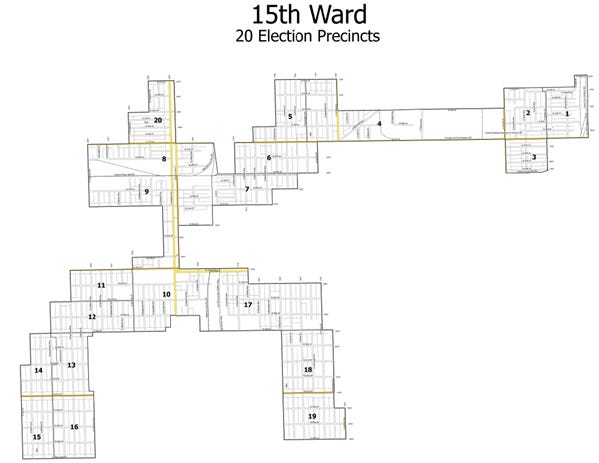

Map of Chicago’s 15th Ward. Turns out this is not the most efficient way to route a garbage truck. Source: Chicago Board of Elections.

But if we don’t address these problems, we’re in for an ugly reckoning. The city is out of money and voters are revolting at the idea of tax hikes. Federal dollars are unlikely to be forthcoming in a Trump administration, and the state is already planning to cut costs ahead of a tough budget next year. If we don’t figure out a way to do more with less, we’ll be forced to do less with less. It’s time to get serious about the problems we’re facing, and the solutions that are required.

In the coming months, A City That Works plans to do just that. We’ll stay focused on structural challenges and long-term outcomes, rather than the wedge issue of the day. We’ll keep writing about the constraints on government, and where they can be loosened. And we’ll share success stories, highlighting the public servants who have helped make Chicago a city that works a little better.

Correction: This piece originally stated that the average affordable unit in Chicago was coming in at a cost of $650,000. It’s actually $600,000, per the linked Crain’s story. My apologies for the error.

[1] It’s not the point of this piece, but for the record, I didn’t think the referendum was a good idea, and A City That Works urged a no vote. But we certainly need more funding to address homelessness in Chicago, and the Progressive Caucus’s statement is a really encouraging sign that eventually we’ll get to common ground here.

[2] It’s important to note that the reported rate of violent crime fell by about half over the same time horizon, according to the linked Crain’s story (that’s still a much smaller decline than the fall in arrests). But those reported rates are sensitive to other variables (less present/responsive police may reduce the willingness to report). Homicides are generally the most reliable data point, because bodies have a nasty way of turning up. In 2006, the city reported 467 homicides. In 2021, that number was 797.

[3] The Orange Line cost $130 million per mile in today’s dollars. The Red Line Extension is set to cost $5.3 billion for 5.5 miles of track, or $964M per mile. That estimate also reflects the heroic assumption that costs don’t increase any further during the construction process. It’s hard to imagine how Chicago ever builds another mile of track, until we get serious about reforms at the national and local levels.

[4] Note that the CTA and CPS have different back-end processes for hiring, procurement, and technology. But they often face similar (if not) worse issues in their own processes.

[5] That includes the left-leaning Roosevelt Institute, the right-leaning Manhattan Institute, and the harder-to-pin-down-ideologically-but-frankly-more-interesting Niskanen Center.

[6] This is something Commuters Take Action has done a really good job of, with respect to CTA hiring – much of the work publicizing the CTA’s reliance on small training classes and requirements to serve as a flagger before a train operator come from their work.

It never stops surprising me when progressives clap back at other democrats for suggesting a better functioning government would be a good thing. The far left has really backed itself into a corner intellectually and I deeply appreciate those working to boost supply-side progressivism.

I'd love to meet with you guys. I have info and experience to share.