Budget Deep Dive, Part 2: Where the City Gets its Money

Even more overview of the Chicago City Budget

Note: As I’ve mentioned in some earlier posts, my objective on some of these deeper dives is to help you better understand the issues facing Chicago. With that in mind, please feel free to reach out at citythatworksnewsletter@gmail.com or in the comments with any questions, suggestions, or or other feedback about pensions, budgets, Chicago, or anything else. I’m more than happy to chat.

In my last post, I went through the basics of the City’s budget and how the City spends its money. Today I’ll be going over the obvious flip side to that coin - where the City gets that money in the first place.

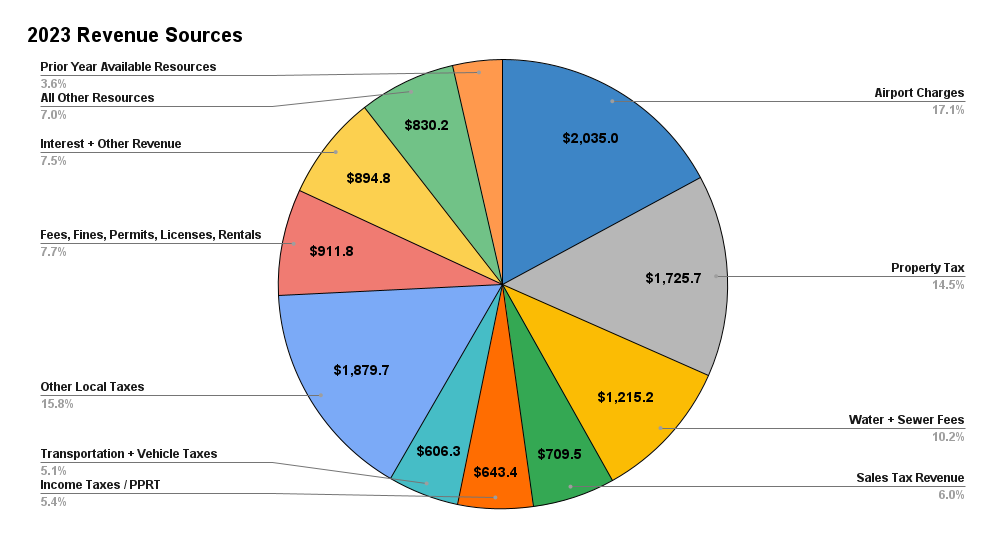

By law, the City of Chicago needs to produce a balanced budget every year. As we covered in the last post, last year the City’s budget included a net of $11.8 billion in spending, so their revenues needed to match that. To make this easy, let’s start with a chart:1

Large Pots of Money we should kind of ignore

As we covered before, a lot of the city’s spending is tied to specific revenue sources, which is useful to keep in mind as we walk through the above - this isn’t one big pool of money that the City can then divide up how they’d like. For starters, the City’s four Enterprise Funds (O’Hare and Midway Airports, plus the Water and Sewer Funds) make up a significant chunk of the above. These are entities intended to work as standalone enterprises, and in that vein it makes sense to regard some of their revenues as standalone as well.

Airport Charges is the single largest source of revenue for the city, and consists of a variety of fees paid by airlines (landing fees, terminal rent, etc) plus non-airline sources such as parking charges and concessions revenue. Notably, the agreement between the airlines and the airport governing these fees (The Airport Use and Lease Agreement, or AULA) specifies that the airlines fees are set on a residual basis - meaning the amount paid varies every year and is set to cover the airport’s operating and debt service expenses (after netting out all non-airline revenue). On the one hand, that means that the airport funds are by definition balanced; on the other it clarifies that there’s no $2 billion in airport revenue which the City could just reallocate to other things if it wanted to do so. At any rate, these fees make up around 17.1% of net revenue for the City, at just over $2 billion. Similarly, Water and Sewer Fees are paid by residents and are intended to cover the Water and Sewer Funds as standalone enterprises. Water Fees were estimated at $934 million and Sewer Fees at $397.5 million, both covering around 90% of their respective Funds’ appropriations (prior year’s resources and various fees, fines, and permits covered the rest).

Property Taxes

After airline fees, the next biggest source of revenue is also probably the one the public is the most familiar with - property taxes. For 2023 the City’s annual property tax levy made up around $1.73 billion, or 15% of total revenue. Property taxes work somewhat different than most taxes people are familiar with; instead of a set rate that raises a variable amount of revenue, each year the City determines how much they need to raise in revenue via property taxes (their ‘property tax levy’), and the County Clerk then calculates the tax rates for the year that will generate that much. For 2023, revenue was roughly flat versus 2022; the City’s tax levy increased by $25 million, but this was based on some expiring TIF districts being incorporated into the tax base (new property they can now tax, rather than higher tax rates on existing property).

The vast majority of these funds - $1.4 billion, or ~80% of the total property tax revenue - goes towards pension funding. Another $294 million goes towards debt service (either the City’s or the City Library’s debt), and about $30 million is transferred to City Colleges of Chicago. I think it’s informative to take a look at how property taxes have varied over time, especially relative to total spending:

Since 2017, total spending by the city is up about 42%, from ~$8.3 billion to $11.8 billion, but the City’s property tax levy is only up by around 28%. In other words, the City has been doing a bit better job diversifying its revenue sources instead of relying on property owners as heavily as possible - this is somewhat nice to see, even as other entities (CPS comes to mind) have failed to do so.

Sales Tax Revenue and Financial Engineering Magic

Another $710 million or so comes from sales tax revenue. This can be broken into two parts:

$90 million from city-imposed sales taxes. These include a restaurant tax, personal property tax, and private vehicle use tax.

$610 million from an entity called the Sales Tax Securitization Corporation (STSC). In a rare development for a city sometimes synonymous with bad financial deals, this is a kind of cool piece of financial engineering worth discussing.

Under Illinois law, the City receives a healthy share of the state’s state-imposed sales tax revenue. Normally, this would get transferred right into the Corporate Fund and be available for spending. In 2017, however, the City created the STSC as a standalone corporate entity entitled to receive sales tax revenue from the state and issue its own bonds. After making the necessary payments (interest plus principal) on those bonds, the remaining revenue every year then gets passed on from the STSC to the City.

You might be wondering why we’d want to create this random corporation acting as middleman between the state and the city just to issue bonds - since Chicago can issue bonds on its own if it wants to. The trick is the rating of those bonds, and how much interest bondholders demand. Chicago is viewed as a somewhat risky borrower by market investors - as of last week, Fitch upgraded the City of Chicago to a BBB+ rating. The STSC, however, is intended to be a standalone, bankruptcy-remote entity which receives its cut of tax revenue - and pays out bondholders - before the City has any discretion to send that money elsewhere. As such, Fitch rates the STSC as AA+, or much safer - because bondholders have the protection of receiving their money at an earlier stage in the game. This might just sound like financial nonsense, but the difference in rating translates directly to a lower interest rate paid on those bonds, which improves the City’s cashflow perspective and leaves more cash available to spend on other priorities. The tradeoff is that we lose some of the ability to not pay back our creditors. It’s a pretty neat tool, and a nice example of how financial engineering, when done correctly, can actually benefit the public in a real way.

Other pots of money

Other local taxes make up another 16% ($1.9 billion) of the budget. These include:

$400 million from public utility taxes (gas, electric, telecom, and cable)

$300 million from recreation taxes (this includes things like liquor, cigarette, and OTB taxes, but the vast majority of it - around $230 million - is the city’s Amusement Tax, which is basically a sales tax on tickets to events like ballgames, concerts, and theater productions in the City).

$125 million from business taxes (mostly a hotel tax)

$800 million from ‘Transaction Taxes,’ which consists of about $200 million in revenue from Real Property Transfer Taxes (assessed on real estate transfers, mostly) and $600 million in revenue from Lease of Personal Property Taxes, a technical term sometimes referred to as the “Cloud Tax” (kind of like a sales tax for SaaS software products)

There’s a long tail of other taxes but that covers the bulk of the revenue in this pocket. I think the key thing to emphasize is twofold:

There’s real money here! There’s a lot of rhetoric around property taxes as the end-all and be-all in public finance, but it’s worth noting how significant a chunk of the City’s revenue comes from these other forms of taxation (to say nothing of the sales tax revenue we already discussed, or of transportation/vehicle taxes, or of the City’s share of income tax revenue too).

Unlike property taxes, all of the revenue from these taxes stem directly from the economic activity taking place in the City of Chicago. If businesses aren’t growing as quickly, if people aren’t coming to visit the city as frequently, if people aren’t going out and spending money in Chicago - then our revenues will suffer.

Considering how much of our budget is fixed spending - remember, 40% is going to just debt and pensions - that has to translate directly into cuts in our day to day basic services. Growth matters.

Non-Recurring Revenue

Eventually the people working on the budget every year run out of pockets of money they think they can count on before they run out of things they’d like to spend money on. This is a problem. While they sometimes address this problem by finding cuts and efficiencies they can make on the spending side, they often also look to identify any other sources of revenue they can come up with to bridge the gap, even if these sources are just one-offs that we shouldn’t count on year in and year out. These are what’re referred to as “non-recurring revenues.”

The biggest example is in the City’s annual TIF surplus, which is ironically a fairly large recurring non-recurring revenue source. Significant portions of real estate within the City of Chicago fall within Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Districts, which divert some of the property tax revenue from those districts into funds intended for infrastructure, redevelopment and growth in those districts, with the goal of revitalizing blighted areas. Any funds not needed for projects in the districts can be declared a ‘surplus’, at which point funds then get allocated to the varying taxing entities (like the City, or the County, or CPS, etc). Over the past few years, these surpluses have gotten larger and larger - for FY 2023, the City declared a surplus of $395 million from these TIF districts, which translated into roughly $100 million in revenue for the City (the remaining $295 million went to those other taxing entities). With consistently large surpluses in TIF districts - implying limited amounts of redevelopment projects to fund - I think it’s pretty reasonable to ask exactly how well served we are by continuing to rely on these districts, particularly when we consider how much revenue this diverts from the City’s general resources. A chart from the Civic Federation’s budget analysis last year highlights exactly how significantly TIF revenue in total has grown recently, compared to the City’s property tax base:

A deeper dive into the city’s use of TIF districts is a post for another day - but if our goal is to expand the City’s revenue sources without hiking property taxes on home owners, it’s worth looking into bringing more of these TIF revenues back into the fold.

Extra Reading

Re-upping some of my recommendations from last time, for an even deeper dive into the City’s budget, both the City’s own budget overview and the Civic Federation’s budget analysis are well worth your time.

And, for a look on the next budget-related topic we’ll be discussing here, readers may wish to take a look at Mayor Johnson’s 2024 Budget Forecast or the administration’s actual budget proposal documents.

Note in this chart that, consistent with the $11.8 billion figure I referenced, I’m ignoring any transfers between funds and proceeds of debt; this is just net revenues.