A better way to build affordable housing

Illinois does a better job paying for affordable housing than Chicago. But there’s still room for improvement.

When I started digging into City’s eye-watering costs to build new affordable housing ($747K per unit, as of 2023), several in-the-know people suggested comparing the City’s costs to projects funded by the Illinois Housing Development Agency.

Thanks to a curious quirk of the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program, Chicago is one of only two cities that gets to award its own low-income housing tax credits.1 That means that there are actually two entities awarding funding to build low-income housing in Chicago: The City’s Department of Housing (DOH), and the Illinois Housing Development Authority (IHDA).

If you compare the processes by which the two agencies allocate tax credits, there’s a few reasons to expect that the State should do a better job controlling costs (and therefore building more units) than the City.

The City’s LIHTC allocation plan doesn’t include any defined preference for lower-cost projects. In fact, it doesn’t include any clear scoring criteria at all – affordable housing developers are playing Calvinball with the Housing Department. In contrast, the State has a clear rubric for evaluating projects.

While the City has an insanely-specific set of design requirements outlined in the Architectural Technical Standards Manual, the State has simpler and somewhat more flexible design criteria that lets developers pick from a menu of options.

The State has a cap on hard construction costs of $398/per square foot (and a 10% higher cap for buildings with higher green building certifications)

State-funded LIHTC projects do end up costing less than city-funded ones – but not by as much as you might hope. Between 2019 and 2023, the annual cost for new state funded projects came in at $454K – which is about 15% cheaper than the city’s figure of $519K.2

That’s not nothing. If the city’s project costs were in line with the projects the state funded in Chicago, 390 additional low-income families would have gotten a decent place to live. But it’s also not good enough. IHDA-supported projects are more than 50% more expensive than projects in Houston, the country’s next largest city. Even in Chicago, high end market-rate developments often cost as much. If we want to make a real dent in the city’s housing shortage, we need to build high quality affordable units for less than half a million dollars a pop.

I’d note that IHDA was quick to share project costs and unit counts when I reached out.3 An IHDA spokesperson cited rising construction costs, noted that affordable developments have unique requirements, and pointed to the Authority’s review process (including requiring independent estimators) to control costs.

I don’t doubt that that IHDA would like to see lower costs – but we’re going to need to be a little more ambitious in order to make that happen. Fortunately, while the city’s funding process needs to be rebuilt from the ground up, there are some straightforward changes to the state’s process that would allow us to build far more units at a reasonable cost.

Make costs a major part of project scoring

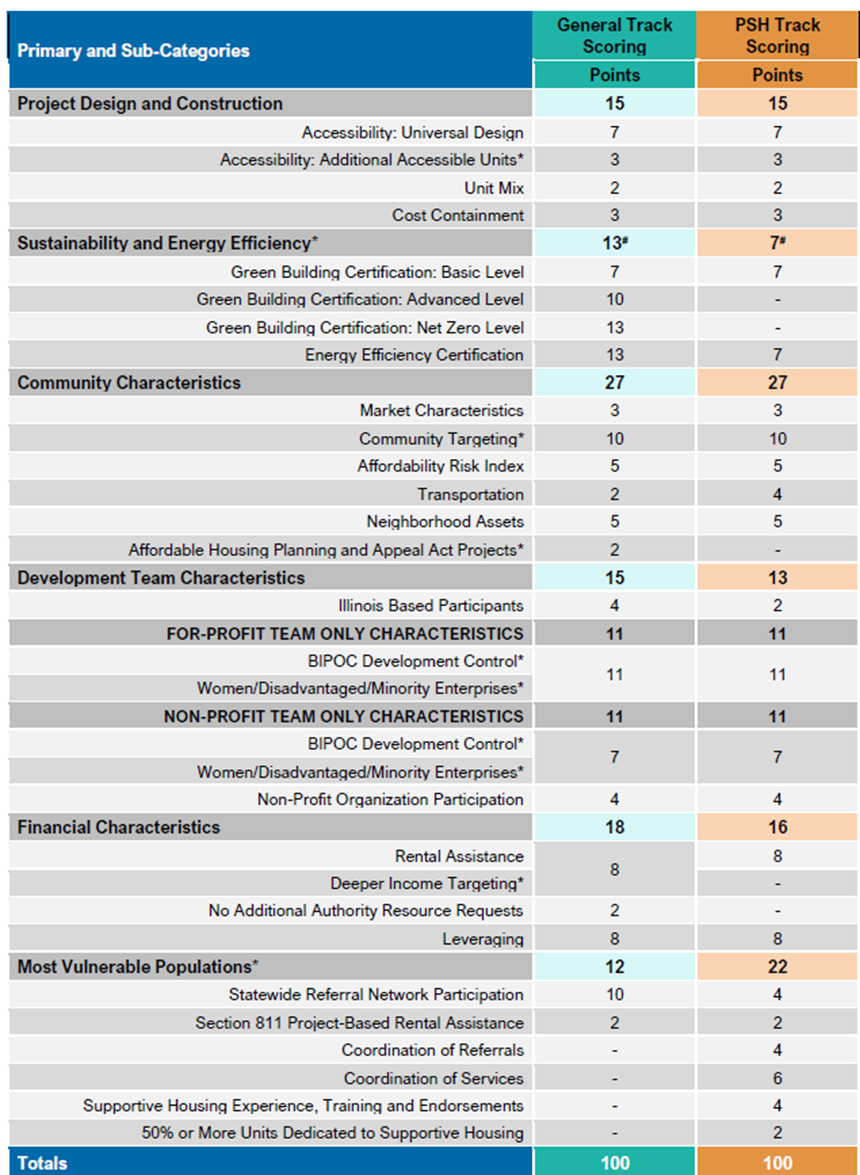

It’s true that IHDA has a more predictable scoring rubric for projects. Unfortunately, that rubric still heavily prioritizes everything-bagel requirements that drive up costs. For the general scoring track, 10% of points are awarded for extra accessibility features, 13% are awarded for additional energy efficiency criteria, 15% are awarded based on the makeup of the development team, and an extra 4% are headed out to non-profit developers. Only 3% of scorecard points are awarded based on project cost.

Source: 24-25 Qualified Allocation Plan

Improving energy efficiency, increasing accessibility, and increasing the diversity of development teams are all worthy goals. But they should be subordinate to our main priority of building more housing. And the less housing we build, the less we can deliver on those other objectives. The city’s current building code has strong accessibility and energy efficiency requirements. But the median unit in Chicago is more than 70 years old. When we build fewer units, we leave more low-income families in inefficient buildings that lack elevators or ground-floor access. And when fewer units translates into fewer projects, we have fewer opportunities for new developers to break into the industry.

Cost containment should get one of the largest weights on IHDA’s scorecard, rather than the smallest. If costs were 30-40% of the score, developers would have a real incentive to design around them – making a million little tradeoffs or decisions in partnership with their architects, contractors, and suppliers that IHDA staff would never come up with on their own. That’s a far superior approach to just relying on a cost cap which developers can partially circumvent by finding other funders for soft costs. And while a cap might control costs in the short term, it won’t create incentives to reduce costs over time.

Raise the cap on project size

In addition to capping hard project costs, IHDA also caps the total size of projects it supports with 9% tax credits. For a number of years now, the largest tax credit allocation a project can receive is 1.5 million – which translates into a little less than $15 million in funding (since the credits are active for ten years but generally sell for a slight discount relative to their face value).4

That puts a hard upper limit on the size IHDA of projects. Between 2019 and 2023, most IHDA-supported LIHTC projects that didn’t include a separate sponsor ranged in size from 30-75 units. And the problem is getting worse – in 2025, every 9% LIHTC application IHDA received in the city limits was for less than 50 units.

But while that size might limit allow for more ribbon cuttings, it’s also a recipe for higher costs. At those sizes, developers generally need to invest in substantial foundation work, elevators, and other core building amenities, but can’t spread those costs over enough units to keep don’t have enough units to efficiently cover those centralized costs. It’s not an accident that the single most cost-effective IHDA-funded project on a per-unit basis also has the highest unit count: the Montclare Senior Residences, which created 134 new units at a cost of $291K per unit ($347K in 2023 dollars).

Montclare Senior Residences. Source: WJW Architects.

Bigger isn’t always better – part of the reason the LIHTC program exists is to move away from the large public housing towers of the past that were cheap to build but left many residents trapped in dangerous and unsanitary environments. But LIHTC projects generally require residents to pay rents that reflect 60-80% of Area Median Income, which means the typical resident is far more stable than may have been the case in the past. It’s also possible to blend income-restricted and market rate units to ensure a higher level of stability. That’s exactly what happened at Montclare, where 34 of the project units are rented at market rates.

But today, the limit on unit count drives up costs. It also forces developers to take insane steps to circumvent the LIHTC limit. One of the worst is a practice called ‘twinning.’ In order to make a larger transaction feasible – especially in situations where zoning and market demand encourage density – the developer creates a separate project on the same site eligible for uncapped 4% federal tax credits.

3959 Lincoln Avenue, for example, is a 66-unit affordable project for survivors of domestic violence. But to fund it, IHDA has received two separate LIHTC applications, one for the 1.5 million maximum possible 9% tax credits (covering 22 units), and another for 4% tax credits covering the other 44.

3959 N. Lincoln Source: LBBA

This isn’t just a weird application quirk – it’s a nightmare for long-term operations. Because the two tax credits are technically separate projects, whoever operates the building will have to do double the paperwork and reporting for the life of the building. And that’s just if things go well – if there are required capital investments in the future that impact both projects (say foundation work, or water damage from 4% units to 9% units) the accounting (and associated costs) get even messier.

The crazy thing is that IHDA knows all of this – the authority even has a guide for developers to help them put together twinning applications to navigate the 1.5 million 9% cap. That’s the institutional equivalent of handing out lifejackets to passengers after drilling a half dozen holes in the bottom the boat. If the state wants to approve more projects, it should take active steps to cut per unit costs, rather than just cutting the size of projects and making the problem worse.

Room for improvement

At one level, these numbers make it obvious that the City’s Department of Housing can’t just blame federal LIHTC rules or rising construction costs for its cost bloat. The state is operating under the same rules, in the same city, and delivering projects that cost significantly less. And there’s more opportunity where that came from. If IHDA updated its scoring criteria and raised its cap on project size, the state could be far more efficient.

The further you go down this rabbit hole, the easier it is to be driven crazy by the dysfunction and missed opportunities under the current system. But if you step back, what actually exists here is an awesome opportunity. If the City and State make some basic reforms, we could be housing hundreds more families a year. In a time of rising rents and tight budgets, that’s worth getting excited about.

It harkens back to a time when the Chicago delegation had clout in DC. North Side Congressman Dan Rostenskowski helped design the LIHTC program and knew who he was supposed to take care of.

Note that while the state’s per-unit cost in 2023 is particularly good, that’s likely a function of small sample size – there was only one qualifying project within the city limits that year. This data also excludes state-supported units in two market-rate developments, that helped ensure more deeply affordable units in high-cost parts of the city but really aren’t comparable to standard IHDA-financed projects. They also didn’t rely on capped 9% LIHTC resources. I’ll write more about those projects in the future.

If you want to follow along at home, that data is available here: 2019 Units, 2019 Funding, 2020 Units, 2020 Funding, 2021 Units, 2021 Funding, 2022 Units, 2022 Funding, 2023 Units, 2023 Funding.

If you’re interested in understanding a little more here, I found this sample calculation on IHDA’s website to be extremely helpful.

LIHTC developer here (not in Illinois). Pretty spot on observations. Never truly considered how bizarre twinning is until now, appreciate the new perspective.

There's no perfect way to control LIHTC project costs, so more tools and point categories is probably warranted. Cost caps can be overly rigid and require projects to build to the bare minimum. They can also box out urban projects where construction markets are more expensive. Per-unit cost caps are unhelpful because they can incentivize bigger units (ie bedrooms are cheaper than kitchens and bathrooms), though you could argue this helps families. A LIHTC award is often first money into a deal. Because it's early and predevelopment phases are getting ridiculously long, costs change/inflate. This makes accurately projecting hard costs when submitting a LIHTC application notoriously challenging. LIHTC developers lobby allocating agencies against adding points for cost projections.

Though there's no silver bullet to cost control, it's pathetic LIHTC application agencies don't even try. These organizations are handing out 10s of millions annually and waste their leverage on pointless point categories that developers know how to game.

How many points does one get for wetting one’s beak?