Note: As I’ve mentioned in some earlier posts, my objective on some of these deeper dives is to help you better understand the issues facing Chicago. With that in mind, please feel free to reach out at citythatworksnewsletter@gmail.com or in the comments with any questions, suggestions, or or other feedback about pensions, Chicago, or anything else. I’m more than happy to chat.

It’s budget season in Chicago. Last month the Mayor’s office released a a 2024 budget forecast projecting financials for the next few years, and they’re expected to release their 2024 budget later this week - possibly later today. We’ll talk about that soon, but that backdrop - and a Twitter exchange a little while ago between Chicagoan Stuart Loren1 and 40th Ward Alderman Andre Vasquez about exactly how much of our budget goes towards policing - inspired a dive into exactly how the City of Chicago spends its money.

So let’s get into it. In 2023, the City of Chicago had a net budget of $11.8 billion dollars2. There are a bunch of different ways we can slice that figure up, but a good place to start is to mention that where a good chunk of that money goes - about 60%3 of total spending - is set in stone.

I know that money is fungible, and transfers between sources make that true in a Chicago context too, but in theory the city has various pockets of revenue that are intended for specific types of expenditures. At a high level, the city has five types of spending funds - the Corporate, Enterprise, Pension, Special Revenue, and Debt Service Funds. Those last four combine to make up that 60% figure I referenced, and are the fixed portion of the budget. Walking through those quickly:

Debt Service refers to money that goes towards paying down Chicago’s existing general obligation bonds (e.g. general purpose municipal bond debt). In 2023, this made up $680.5 million, or roughly 5.8% of all net spending.

Enterprise Funds are four self-supporting funds (as in, they have their own revenue sources) that are intended to operate like commercial enterprises (hence the name). The four funds in question are for the City’s water system, the City’s sewer system, O’Hare Airport, and Midway Airport. In 2023, these made up $3.4 billion in spending, or around 29% of the budget.

The Pension Fund should be familiar to readers, since it’s something we’ve covered before, and encompasses roughly 22.7% (or $2.7 billion) in city spending. That’s the money that flows into the city’s four employee pension systems (police, fire, labor, and municipal). For the most part, this spending is non-negotiable; as of 2022 the City is required by law to make the actuarially required payments into these four systems. For 2023, the City actually went a bit above and beyond that required payment, making a $242 million “Advance Pension Payment”4 in addition to their statutorily required contributions.

Special Revenue Funds encompasses spending where a specific tax or source is earmarked only to finance a particular function. As an example, Chicago has a vehicle tax (you have to buy a sticker every year for your car), and the revenue from that tax pays for the upkeep of Chicago streets (incidentally, this is the largest special revenue source). Others include the Motor Fuel Tax Fund (which pays for upkeep of the right-of-way - streets, sidewalks, etc), the Library Fund (library rental fees, which help pay for the Chicago Public Library system), and the Garbage Collection Fund (a monthly fee for garbage collection which helps pay for garbage collection). As a whole, these all make up just under 10% of City spending.

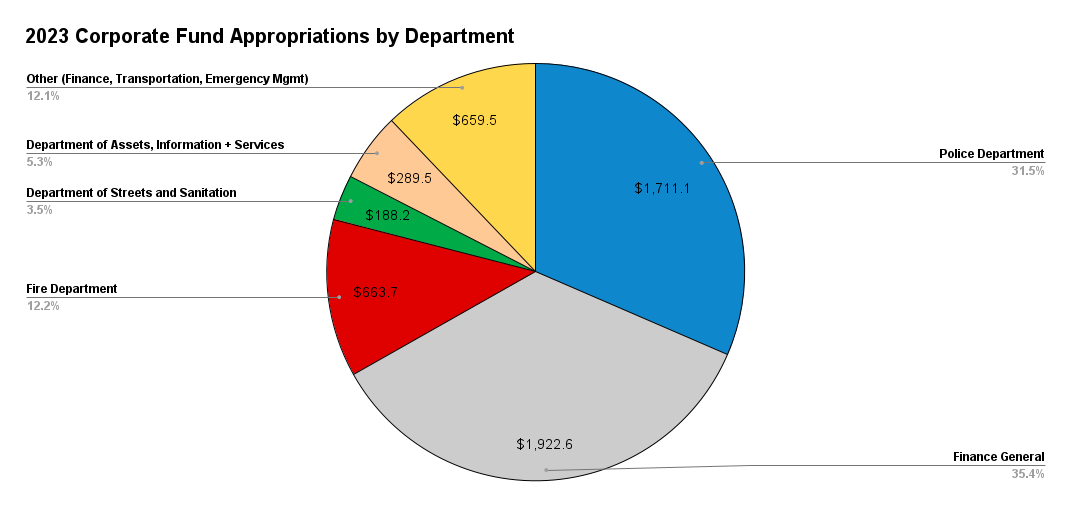

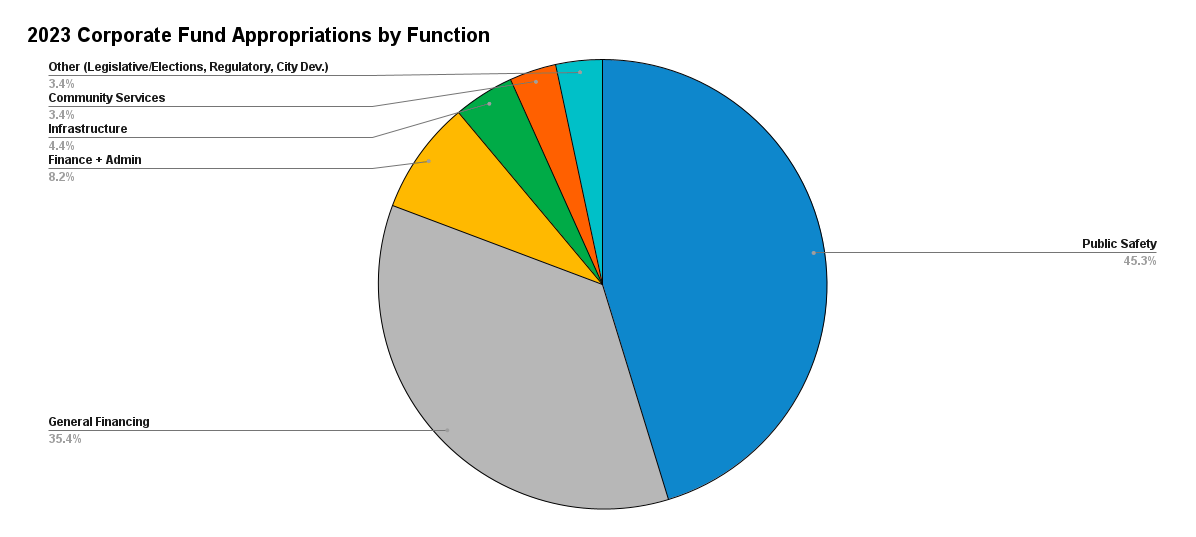

That leaves the Corporate Fund, which is $5.4 billion or 46% of net spending5. This is the City’s general operating fund and is where we spend money on the stuff you probably think about most often in terms of “what the city does.” This is also the portion that’s really more up for debate each year and gets negotiated during budget season. When there’s a shortfall in revenue, it’s the fund where the cuts need to come from, and when there’s a surplus it’s where the City can allocate funds for new investments or projects. Per the Civic Foundation, here’s a look at how those funds were divvied up across the city’s departments in 2023:

The City’s budget also regroups this spending together by ‘function’, for another view:

Remember, those percentages above are only of the Corporate Fund, not of all total spending. Helpfully, however, if we unpack the City’s supplemental Budget Recommendation info a little, we can replicate this for all spending, too6:

It’s the pensions (and debt), stupid

One thing should immediately stand out here: nearly forty percent of the budget here is going towards either pensions or debt service. That’s an incredibly high percentage of government spending that’s going to pay for things that already happened in the past.

How does this compare to other similar big cities? Not well:

In New York, pensions and debt service for FY 2023 make up a total of about $17 billion out of the city’s $109 billion budget - or roughly 15.6% of city spending combined.

In Los Angeles, pensions appear to be pretty comparable to Chicago, with contributions around 20% of the city’s budget - but debt service is significantly lower, in the 4-6% range.

In Philadelphia, pensions and debt service combine for about 17.3% of the city’s expenditures for FY2024.

At the risk of beating a dead horse, this remains Chicago’s greatest public policy challenge - escaping a legacy of poor fiscal management that continues to eat away at our budget, and likely will going forward.

Don’t forget the police

After debt, pensions, and general finance, public safety makes up around 20% of the overall budget - and since the police make up about two-thirds of the public safety budget, the Chicago Police Department is around 13% of the overall budget7. The Civic Federation has a really nice overview of the CPD budget from last month, and it’s worth your time, but to cover some of the basics:

Last year, we budgeted for around 14,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) personnel within CPD, reasonably flat over the past couple years, though down versus 2018-2020:

Our actual number of CPD employees has been below this budgeted number, with only ~12,300 CPD employees as of August 2023. Around 93% of CPD employees are sworn officers, and as of August 2023 CPD had ~11,700 actively assigned sworn officers - this is fairly flat over the past year, though down around 12% from its peak in late 2018:

Another note, based on the above - with ~12,000 officers in a city of 2.7 million, Chicago has roughly 44 police officers for every 10,000 residents. That’s actually pretty high in the context of most major cities - New York and Philadelphia are pretty similar, with 40-42 officers per 10,000 residents, while other cities like Houston, LA, San Francisco, Jacksonville and Dallas all have nearly half that ratio (20-26 officers per 10,000 residents). To be honest, I’m pretty skeptical to believe that Chicago is over-policed at the moment, but these figures certainly suggest to me that the raw number of active officers is not the primary issue with respect to recent crime.

What doesn’t this include?

Any number of big agencies are conspicuously not included in the above - Chicago Public Schools, the Chicago Transit Authority, and the Chicago Park District all stick out as big obvious examples8. These are all separate entities which are governed and funded separately, and thus don’t get included in the city’s budget. If you want to analyze the city’s budget, this probably has at least three effects I can think of off the bat:

It makes “police spending” (or public safety spending, if you want to include fire, too) as a share of total municipal spending look larger than it otherwise would, since we’re ignoring a great deal of school, park, and transit spending from the total expenditures. Those dollars don’t go through City Council, so they’re not “city spending”, but if you want to know where your tax dollars are ultimately going they’re certainly something you still care about.

It makes “expenditures per resident” or any similar metrics look smaller than they otherwise would - again, if I’m only looking at a portion of total municipal spending, then I’m missing some of the picture you probably care about.

They potentially skew those “percent of municipal spending going to debt and pension payments” numbers I just covered, because in theory if all of our school spending and parks spending and public transit spending is going towards government services we’re consuming today, and not on old benefits, then me taking this as an opportunity to re-emphasize the pension/debt issues is misleading. I feel reasonably comfortable that I am not in fact misleading readers about these issues, though we can delve into these other agencies down the road.

Extra reading

I think the above should provide a pretty good backdrop to think about how and where the City spends its money. I hope it’s useful information to have as we wait for the first budget from the Johnson administration.

That said, if you do want to get further into it, for an even deeper dive into the City’s budget, both the City’s own budget overview and the Civic Federation’s budget analysis are well worth your time.

I’m not actually sure what biographical description to refer to Loren, but he’s a Chicago investment professional who amassed a pretty active Twitter following throughout the 2023 mayoral campaign, and he often has good policy analysis on financial/economic issues.

Note: You may in some places see either $16.4 billion as the total 2023 budget. That total includes $4.6 billion in grant funds the City received, which are largely indexed for specific purposes and are somewhat tangential to the overall budget process. I’m excluding them from this analysis. You may also occasionally see $13.3 billion as the total budget figure. That figure includes some double counting, based on how the City moves money around between spending funds. Once you net out those transfers, $11.8 billion is the actual figure of total net spending by the City.

For transparency: my math here is looking at non-Corporate Fund spending divided by all Local Funds Spending (for 2023, this was $7.903B out of $13.337 billion, or 59.3%), so I’m not netting out the transfer portion.

Incidentally, this is an example of the double counting issue described in footnote 2. $202 million of that advance pension payment was a transfer from the Corporate Fund into the Pension Fund - so it’s not right to count that portion as both $202 million in Corporate spending AND $202 million in Pension Fund spending; you should only count that $202 million once.

Mathematically inclined readers will notice the percentages of these funds add up to 113% - that’s again because of the double-counting issue in footnote 2, since my percentages here are of the $13.3 billion figure.

Specifically we’re looking at Summary E, beginning on PDF page 25 of that link. Note that I’ve split the “General Finance” portion out to show Debt Service and Pension Fund payments separately - this was copied straight from the Civic Federation, who did the same thing here, and makes sense to me to do.

Note that this does NOT count contributions to the Police Pension Fund as police spending or as public safety spending.

I apologize to the heads of any other city agencies I am inadvertently slighting by not including in this list.

Excellent analysis, sir. Just a comment on the other agencies: they do not spend all their dollars on current items. They, too, are mired in the overwhelming problem of pension and other debt for their employees.

Also, the cost of each city employee constantly escalates, also ballooning the cost of govt. With each police and fire contract, the wage increases create larger pension obligations.

But please keep going with your analysis.