Something Great Just Happened on Western Avenue

A recipe for more tax revenue, lower rents, and cleaner politics

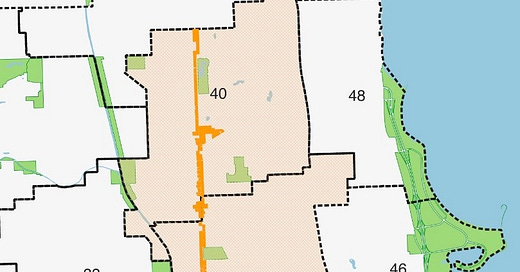

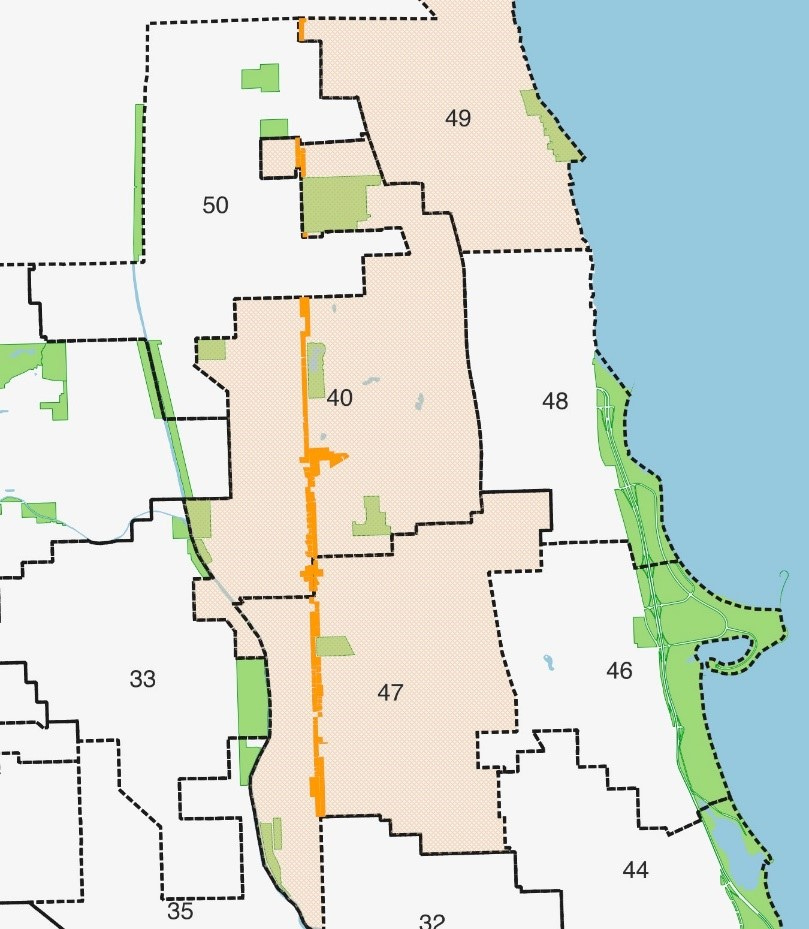

Areas upzoned to B3-3 under the Western Avenue upzoning. Ald. Debra Silverstein’s (50th) Ward is noticeable for its lack of participation. Credit: Steven Vance.

Between the drama engulfing Chicago Public Schools and the City’s own budget woes, the next few months are going to be tough. So let’s take a minute to celebrate a straightforward progressive win that reflects real leadership on the part of some local elected officials.

Two weeks ago, the City Council finalized a broad-based upzoning of Western Avenue covering most of the area from Howard to Addison. This is the result of hard work by local Alders Andre Vasquez (40th), Matt Martin (47th), and Maria Hadden (49th), as well as staff at the Department of Planning and Development (DPD). It’s good policy, smart politics, and just might be a template for better land-use decisions across the city.

The number of housing units allowed in the affected area will rise from about 2,800 to roughly 6,800, according to Chicago Cityscape founder and planning guru Steven Vance. That has major benefits. Study after study shows that adding density helps make housing more affordable: when tenants have more options, landlords have less market power and rents stay lower. And to the extent that these units help Chicago attract or retain residents, they’ll spread our pension and property tax burden over more people, making it easier to confront our fiscal challenges.

There are also environmental and transit benefits. Denser housing reduces sprawl and cuts carbon footprints, as residents drive less and are more likely to rely on public transportation. And as Niskanen Center housing analyst Alex Armlovich notes, the upzoning also increases Chicago’s odds of attracting federal funding for Bus Rapid Transit investments on Western Avenue.

More housing at lower cost

In Chicago, most upzonings are one-off deals between the local Alderman and the developer of a specific property. As you might imagine, that’s been a major thread in Chicago’s rich tapestry of corruption. When former Alderman and Zoning Committee Chair Danny Solis went down, his federal indictment included political favors exchanged for campaign contributions, Viagra, sexual favors, and access to a luxury farm once owned by Oprah.

Today, in many progressive wards Alders use a “community-driven” zoning process instead.[1] During that process, a developer presents a series of designs to neighborhood residents, and then engages in an extended negotiation about the size and design of the building (plus any number of other benefits residents or community groups advocate for during the process). It’s reasonable for neighbors to want to have a say in how their community changes, and it’s more transparent and less corrupt than a series of back room deals.

But rounds of neighborhood input can take months or even years. And until the Alderperson signs off, developers can have no idea if or when their application will ever be approved.

That’s extremely costly. Developers have to raise capital, buy a property, design a project, and then pray that it gets through the upzoning process. In a 2023 paper, UCLA researchers estimate that with an 8% interest rate, those costs can run $1,200-$4,000 per unit per month in Los Angeles.[2] That means a 50-unit project is burning up to $200,000 a month in financing costs during the approval process. That’s just the cost of capital -- not money that turns into affordable housing, or better construction wages, or even dog parks for nearby neighbors. It’s just wasted.

That $200,000 a month also doesn’t account for the direct costs associated with creating designs (updated for each round of neighborhood feedback), and any additional costs or lost units as a result of the negotiation process. The UCLA researchers also point out that the uncertainty can be even worse than a delay. Small developers don’t carry a lot of projects, so the prospect of delays on a project may prevent them from raising financing for that project in the first place. Or worse - one long-delayed effort can sink their business.

I’m not asking you to shed a tear for developers. The problem is that when projects are much more expensive and uncertain, the only ones that can get financed are high-end buildings with rents pricey enough to justify those costs. And with fewer projects financed overall, Chicago faces a housing shortage, as more households chase the same number of units. That’s a recipe for rent hikes.

Delays are also worse for developers of affordable projects or projects in neighborhoods that don’t get much investment. When projects can’t easily attract private sector funding, developers have to build a ‘lasagna capital stack’ with layers of funding from state, city and community sources—any slice of which can be at risk if a project gets hit with unexpected delays.

Upzoning before a developer ever proposes a project fixes a lot of these problems. Instead of holding capital for months and rolling the dice on community approvals, developers can raise money, buy property and build with certainty. In LA, the shift to by-right approvals caused projects to get built 28% faster, increased average project size, and increased the number of affordable units. We can expect something similar on Western. Developers will be able to build sorely needed housing faster, investments that couldn’t be justified under the previous regime will pencil under this one, and developers of affordable projects will be at less of a disadvantage.[3]

A model for better housing politics

Vasquez, Martin and Hadden aren’t just being smart progressives. They’re also being smart politicians.

The challenge with approving a new development is that while we all benefit from new housing, residents in the immediate vicinity perceive localized downsides—traffic, parking, shadows, neighbors with different backgrounds or income, or just a general antipathy to change. That’s why national Democrats are supportive of loosening zoning laws, but local Alders often send projects back to the drawing board.

Research backs this up. Michael Hankinson at the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies finds that homeowners are far more likely to mobilize against a hypothetical development right next door than one a mile away.

Homeowners are far more likely to oppose developments within a half-mile radius. Source: Hankinson

But when a developer requests an upzoning for a specific parcel, the only residents who likely even hear about the project are the immediate neighbors. It’s the worst of both worlds: nearby residents see a big scary building to mobilize against, but approving a single project will barely move the needle on the city’s broader housing shortage.

The Western Avenue upzoning flips the script. There is no scary development to oppose. Community members have had extensive input on a broader plan for the corridor. But that input is part of a holistic vision, not a community meeting designed to mobilize the worst version of NIMBYism. And the benefits are more tangible: Martin and Vasquez can sell residents on a vision that benefits a swathe of the city, with broader benefits for affordability, walkable streets, and local businesses.[4]

Encouragingly, other Alders are moving in the same direction. Alderman Carlos Ramirez-Rosa (35th), who has previously championed counter-productive down-zonings, just proactively upzoned a strip mall on Milwaukee Avenue. Alders Nicole Lee (11th) and Julia Ramirez (12th) are exploring upzoning a stretch of 35th Street. And a land use planning effort is kicking off on Broadway, covering parts of Angela Clay (46th), Martin, and Hadden’s wards that could be another upzoning opportunity. If you’re interested in nudging these along, I’d encourage you to sign up with the good people at Urban Environmentalists Illinois who are helping mobilize public support for these efforts.

Of course, there are a few things to watch out for as these efforts move forward. As Vance noted in his testimony to the Zoning Committee, these upzonings should also proactively allow access to the transit-served location benefits of the Connected Communities Ordinance, to ensure that developers don’t still have to go back through the approval process. It’d be nice to see upzonings on smaller streets as well, rather than just packing apartments onto high traffic, high density arterial roads.

Most importantly, while it’s helpful to make these choices in the absence of a single project or developer, Alders and their staff will need to pay close attention to ensure upzonings and other changes are big enough to generate new development. There’s no point to proactive upzonings that are too small to help new construction pencil. Without a specific project on the table, Alders will need to coordinate more closely with the development community to ensure that these upzonings will make a difference.

It’s also worth noting that efforts to impose design guidelines or community overlays without new upzoning, such as the design guidelines recently imposed on Milwaukee Avenue, are actively counterproductive. Anything that would’ve been built by-right is now just a bit more costly, while a developer hoping for a zoning change still has to go through the full zoning process.[5]

The next few months are going to involve some hard choices, as the city attempts to pull together a budget without the benefit of federal ARPA funds. But that doesn’t mean we can’t continue to find ways to push the city in a more prosperous, progressive, and ethical direction. Martin, Vasquez and Hadden have hit on a good one. Let’s hope other members of the City Council follow.

[1] While it’s certainly true that members of the ward participate in these processes, they’re rarely representative of the community: studies indicate participants are generally older, wealthier, and more likely to be white than voters in the neighborhood as a whole.

[2] That assumes an average unit cost of $600,000. The range is dependent on what share of financing must be raised up-front. Notably, even if it’s a smaller share, that share is likely equity, which is the most expensive part of the capital stack.

[3] It’s also worth noting that the city’s Affordable Requirements Ordinance still applies, which means that developments benefiting from the zoning change need to include affordable units at the same 20% rate that would be required if parcels were upzoned individually.

[4] Also, the Affordable Requirements Ordinance (ARO) still applies to the proactive upzoning, so the city isn’t getting any fewer affordable units than it would if parcels were upzoned individually.

[5] It’s ironic – if stuff is old, we add rules to make new construction blend in. But if we’re building new stuff, design guidelines actively reject standardized looks. I once had a city staffer tell me that he was trying to prevent the construction of “cookie cutter housing.” I wonder what he thinks of bungalows and 2-flats.

It's refreshing to see the recent attention paid to the disastrous effects of zoning, "community input", etc. on the incentives for housing developers to build. Very glad to hear about what happened with Western Avenue; also I highly recommend Matthew Yglesias's Substack for numerous high quality articles on the legal and logistical cluster**** you'll encounter if you try to build an apartment building in a typical American city, and what's being done about it.